Ancient Maya warfare flared up surprisingly early

Extreme conflicts broke out well before the civilization’s decline, researchers say

WAR BURNS A fragment of an inscribed stone monument found at the Maya site of Witzna contains a dark, burned patch near its right edge. A 697 attack on Witzna left the monument broken and scorched, scientists say.

Francisco Estrada-Belli

In 697, flames engulfed the Maya city of Witzna. Attackers from a nearby kingdom in what’s now Guatemala set fires that scorched stone buildings and destroyed wooden structures. Many residents fled the scene and never returned.

This surprisingly early instance of highly destructive Maya warfare has come to light thanks to a combination of sediment core data, site excavations and hieroglyphic writing translations, say research geologist David Wahl of the U.S. Geological Survey in Menlo Park, Calif., and his colleagues. Organized attacks aimed at destroying cities began during ancient Maya civilization’s heyday, when Witzna and other cities thrived in lowland regions of Central America, the scientists report August 5 in Nature Human Behavior.

Maya civilization’s Classic period ran from around 250 to 950 (SN: 10/27/18, p. 11). Many investigators have assumed that intense military conflicts occurred between 800 and 950, contributing to the Classic Maya demise. Researchers have often assumed that, before 800, Maya conflicts consisted of relatively small-scale raids aimed at taking high-status captives for ransom or sacrifice.

Wahl’s group first noted that hieroglyphic inscriptions on a stone slab at the Classic Maya city of Naranjo state that Witzna was attacked and burned by Naranjo forces for a second time on May 21, 697. Naranjo was located about 32 kilometers south of Witzna. Those inscriptions provide no details about a first Naranjo attack. Writing on the slab uses the term puluuy to refer to Naranjo’s burning of five cities including Witzna, over a five-year span. Some scholars suspect that puluuy attacks targeted only select temples or sacred caves, rather than entire settlements.

But the conflagration at Witzna was large enough to leave its mark on the landscape. A lake sediment core extracted about two kilometers from Witzna’s ceremonial center contains an unusually thick layer of burned wood fragments radiocarbon dated to between 690 and 700, the researchers say. That sediment layer marks the largest fire documented in the core, which spans the last 1,700 years, the scientists say. Signs of reduced human activity, including low erosion rates, appear in core layers that formed after the massive fire.

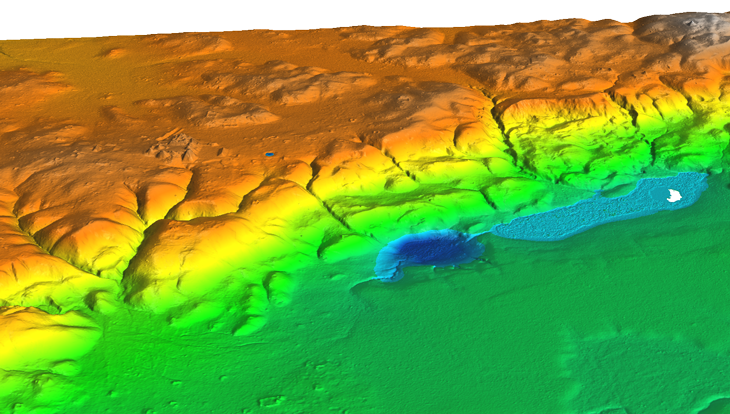

Attack site

Airborne laser data generated an image of ancient Witzna’s ceremonial center, shown in blue, extending for two kilometers along a limestone ridge. Much of this area was burned in an attack launched in 697 by a nearby kingdom, researchers say.

“What is unique [in the new] study is that the effect of a military conflict appears to be reflected in lake core data,” says archaeologist Takeshi Inomata of the University of Arizona in Tucson, who was not involved in the research. In line with those results, excavations across Witzna in 2016 revealed signs of extensive fire damage to many structures, including the royal palace and the city’s inscribed monuments, that occurred between roughly 650 and 800.

The new findings “link a significant burning event at Witzna to abandonment of the site a century or more earlier than has been reported elsewhere in the Maya lowlands,” says anthropological archaeologist Andrew Scherer of Brown University in Providence, R.I. By linking Witzna’s burning and abandonment to the timing of a recorded attack on Witzna, Wahl’s team argues against the possibility that an escalation of slash-and-burn farming in the late 600s caused the Witzna fire, Scherer contends.

After the presumed 697 attack, Witzna’s royal family clung to power for at least a century in a downsized settlement, the researchers say. Excavations indicate that the royal palace was rebuilt during the 700s. Evidence of Maya wars that toppled royal dynasties at other sites dates to after around 800, they say.

Still, the extent of Classic Maya warfare remains poorly understood, says archaeologist Elizabeth Graham of University College London. Rules of Maya warfare apparently changed after Naranjo’s attack on Witzna, she contends. Aside from the vanquishing of losing kings in later wars, hand-held spears largely gave way to projectile devices known as atlatls that enabled longer and more powerful spear throwing after around 800, Graham and a colleague reported in 2015.

Prior to 800, Maya people may have considered it dishonorable to kill or wound others from a distance, Graham suspects. Classic Maya culture probably discouraged killing large numbers of opponents in battle with any type of weapon, since no mass burials of war victims have been found, Inomata says.