The blinking of a distant star may be chronicled in an ancient Egyptian calendar created more than 3,000 years ago to distinguish lucky days from unlucky ones.

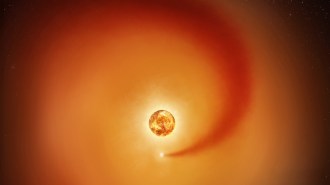

Known today as the Demon Star, the three-star system Algol sparkles in the constellation Perseus, near the eye of Medusa’s severed head. Observers on Earth can see Algol twinkling when the two closest members of the system eclipse one another: Every 2.867 days, as the dimmer star crosses between Earth and the brighter star, the Demon Star’s light appears snuffed.

A repeating pattern of similar duration appears in the Cairo Calendar, a roll of papyrus dating to 1271 B.C. that characterizes each day as all good, all bad or a mix. The occurrence of all-good days matches Algol’s brightness fluctuations, researchers from the University of Helsinki report in a paper posted April 30 on arXiv.org.

“They seem to have established rather clearly that there is a periodicity,” astrophysicist Peter Eggleton of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, says of the team’s analysis of the calendar. “What they haven’t established to my mind is that it is most likely due to a variable star.”

The calendar’s oscillation is a little faster than what astrophysicists observe when they look at Algol today — 2.850 days instead of 2.867 days. But that’s relatively easy to explain — for example, the spinning stars could have slowed down a bit over the past three millennia because of magnetic interactions, stellar winds, or mass exchange, Eggleton says.

What’s lacking is any direct evidence that the Egyptians actually kept track of Algol’s twinkling while offering prognostications.

“The lack of a firm connection to Algol makes it a bit of a leap for me,” says astronomer Bob Zavala of the U.S. Naval Observatory in Flagstaff, Ariz.

Pulling the pattern from the calendar required a feat of statistical endurance. Eventually, the researchers uncovered two oscillations: a 29.6-day cycle, and a 2.85-day cycle. “They’ve done a considerable amount of work, and quite detailed,” Zavala says.

The longer cycle is probably lunar. But at first, scientists weren’t sure what could have produced the shorter frequency.

They found their match in the General Catalogue of Variable Stars. “Nobody knew that there would be Algol in this data,” says astronomer and study coauthor Lauri Jetsu. “It was a surprise for us.”

Then, the team considered whether Algol would have been visible to ancient Egyptian scribes. Among other criteria, the scientists looked at the star’s brightness and position in the sky — and concluded that Algol’s winking would not only have been visible, but is also the only plausible source for the oscillation recorded in the calendar.

“We were initially skeptical about the result as well,” says study coauthor Sebastian Porceddu. But he points to evidence that the ancient Egyptians based festivals and calendars on mythologically important astronomical objects, and says the 2.850-day period is too significant to be accidental. “The scribes must have inserted it,” Porceddu says, noting that the team has a manuscript in preparation detailing these connections.