A few years after Francis H. Crick and James D. Watson unveiled the structure of DNA in 1953, they rocked the fledgling field of molecular biology again with a bold notion: Viruses are, in part, structured as crystals are. That idea captivated Donald L.D. Caspar and Aaron Klug, who then systematically applied what they knew about crystal geometry to classify and predict the structures that many viruses might assume. The motif that stood out time and again was a set of symmetries seen in various structures, including soccer balls, spherical geodesic domes, and the 20-sided, jewel-like shape known as the icosahedron. Since the 1960s, Caspar and Klug’s work has been the framework for explaining and predicting many of the most prevalent viral configurations.

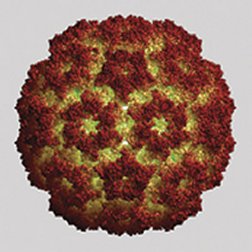

Over half of all virus families have shells with icosahedral symmetry. Among their ranks are many harmful and deadly agents, including those responsible for herpes, polio, hepatitis, some cancers, and the common cold and other respiratory infections.

Over the decades, however, an important basic question has persisted: What physics dictates that so many viruses have icosahedral shapes? What’s more, why do the structures of some icosahedral viruses—among them polyoma-type viruses, which are associated with some cancers, and L-A, a yeast virus—fall outside the Caspar-Klug framework.

Some physical scientists and mathematicians have recently begun to apply their favorite tools to these questions, thereby bolstering the study of viral structure.

“People from physics and chemistry have joined the biologists,” says theoretical physicist Joseph Rudnick of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). “It’s an exciting time in terms of the study of viruses.”

As the scientists clarify the fundamental architectural rules of these entities on the border between the living and the nonliving worlds, they also find themselves on track toward practical payoffs. “The ultimate goal,” says mathematician and virus investigator Reidun Twarock of York University in England, “is to open up new avenues of antiviral drugs.”

Disco virus

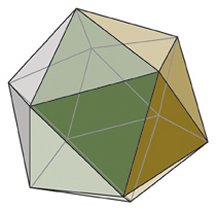

With its 20 triangular facets, an icosahedron resembles a simplified disco ball. A key trait of an icosahedron is fivefold symmetry. At a dozen locations on an icosahedron’s surface, five facets share a common vertex, as petals of a flower share a center point. Rotating the icosahedron around any of those vertices by one or more fifths of a full turn results in a figure that looks exactly as if the icosahedron hadn’t rotated at all. Icosahedra also have locations around which there is threefold or twofold symmetry.

Besides soccer balls and geodesic domes, other objects ranging from cagelike fullerene molecules and some microorganisms called diatoms to the dice used in games such as Dungeons and Dragons manifest that same set of fivefold, threefold, and twofold symmetries. Collectively, this characteristic is called icosahedral symmetry, even when the object isn’t 20 sided.

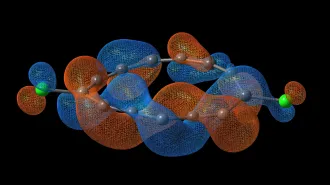

In the nanometer-scale world of viruses, icosahedral symmetry is widespread. Every virus harbors an inner pearl of genetic material—DNA or RNA—encased within a protective protein shell called a capsid. Using mathematical arguments and evidence for icosahedral symmetry in X-ray analyses of various viruses, Caspar and Klug proposed that those viruses referred to as spherical viruses—because under microscopes they look like balls—actually have icosahedral symmetry. Scientists often refer to this class of viruses simply as icosahedral viruses.

Caspar and Klug were prepared for this leap, in part, by the then-new architectural concept of the geodesic dome conceived by R. Buckminster Fuller. In their viral version, the two scientists claimed that they could account for all viruses that have icosahedral symmetry, no matter what their size, using one simple recipe: Place one pentagon at each of the 12 sites of fivefold symmetry and then fill the rest of the shell with hexagonal units. Each of those pentagonal and hexagonal panels represents five or six proteins, respectively, that serve as building blocks. Virologists refer to these panels as pentamers and hexamers or, collectively, capsomers.

For the most part, the Caspar-Klug scheme has worked beautifully. To this day, it accounts for the geometry of nearly all icosahedral viruses. But Caspar and Klug didn’t experimentally seek the fundamental physics underlying their descriptive formula. Others now have.

“The majority of spherical viruses have come up with this icosahedral symmetry, so there must be a more general principle at work,” remarks Rudnick’s colleague, physicist Robijn Bruinsma. Indeed, he, Rudnick, and UCLA chemist William M. Gelbart were struck by the fact that experiments dating back to the 1960s showed that viral capsids with icosahedral symmetry will form spontaneously in a solution of capsid proteins, given the right conditions of temperature, pH, and salinity.

Similar conditions govern the crystallization of minerals. The guiding principle for inorganic crystallization is the minimization of energy. The lowest-energy crystal geometry that is possible under a given set of conditions is the one that is most likely to form.

Could it be that icosahedral symmetry provides the lowest-energy spherical capsid structure? Caspar, Klug, and other pioneers of viral-structure theory made that assumption. To test it, the UCLA scientists and their colleagues recently undertook an experiment in pure geometry.

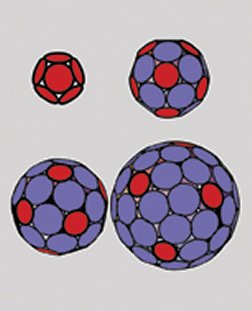

They developed a computer model that treated capsomers as malleable disks. They assigned each pentamer to occupy 72 percent as much area as each hexamer did. Then, by having the computer repeatedly shuffle those disks into arbitrary arrangements on a spherical surface, they simulated the formation of millions of hypothetical capsids.

In each configuration, the faux capsomers would push and tug on each other with forces whose values the researchers assigned, in part, according to measurements of real viruses.

For successive numbers of disks from 12 to 72, the researchers started with the capsomers scattered across a spacious sphere and slowly shrank it until the capsomers became crowded together. The researchers tracked the ups and downs of energy, noting with particular interest the lowest energy, which indicates the stablest configuration. To explore all possible ratios of pentamers and hexamers, the researchers also programmed into the process random switching of disks between the two types.

In the end, a few of the configurations yielded energies far lower than the others did, the team reported in the Nov. 2, 2004 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The lowest-energy configurations emerged during the modeling runs with 12, 32, 42 and 72 capsomers.

Those capsomer counts correspond perfectly with those of the four predominant classes of viruses with icosahedral symmetry that Caspar and Klug had identified in the 1960s. Moreover, in addition to their hexamers, each of those configurations featured just 12 pentamers strategically located as required for icosahedral symmetry.

The PNAS report “answers a very important and fundamental question,” says Twarock. “Why do viruses have this symmetry?”

Theoretical physicist David R. Nelson of Harvard University agrees that the work “explained a remaining mystery.”

Polly wanna crystal?

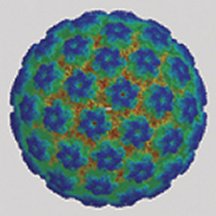

In the early 1980s, researchers began finding viruses, such as polyoma, that don’t fit the mold of Caspar and Klug’s theory.

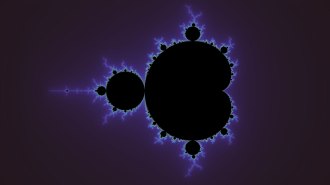

Twarock began considering those discrepancies in 2003, when she was working on quasicrystals. Quasicrystals are structures of many subunits, but unlike conventional crystals, the subunits can differ. What’s more, they don’t assemble into obvious repetitive patterns (SN: 12/16/00, p. 399: Available to subscribers at A hard new material with a soft touch).

A virologist colleague had shown Twarock a 1991 scientific article that reported that every one of the 72 capsomers of a polyoma-type virus called Simian Virus 40 (SV-40) is a pentamer. That was troubling, not only because Caspar and Klug’s theory doesn’t permit such a configuration but also because it was well known, even to floor tilers, that five-sided units can’t lie side by side in a seamless pattern.

Funny things can happen with quasicrystals, however. For instance, a quasicrystal can form a pattern that, as a whole, has fivefold symmetry as pentagons do but, unlike a tiling of pentagons, can cover a flat surface seamlessly.

Twarock and Jiøí Patera of the University of Montreal had previously devised mathematical models for constructing certain quasicrystals. As soon as Twarock saw the polyoma puzzle, she began seeing connections. “With my training in quasicrystals, I knew what was needed,” she says. She realized that these new mathematical tools might solve the mystery of standout viruses such as polyoma.

The technique employs some mind-bending concepts, such as a six-dimensional lattice based on a hypercube or other building block. Twarock considered lines and planes projecting from such a lattice onto a three-dimensional sphere representing a viral capsid.

The new quasicrystal-inspired framework indicated how a multitude of pentamers could arrange into seamless capsids. What’s more, the framework showed how smaller groupings of proteins could tile into a variety of shapes, among them triangles and diamonds. Twarock outlines her approach in the June Journal of Theoretical Medicine.

Exploring the expanded portfolio of possible capsid structures that her tiling method had revealed, Twarock found a tile arrangement for a capsid comprising 72 pentamers and no heptamers. It was exactly the structure described in the 1991 SV-40 paper.

Trying other constructions, Twarock generated a pattern of diamond tiles that reproduced the capsid structure observed for another virus that challenges the Caspar-Klug model. MS2 is a member of a class of viruses, called bacteriophages, that attack bacteria (SN: 4/9/05, p. 235: Available to subscribers at Phages take breaks while ejecting DNA). Its shell is made of a single type of capsomer that has three proteins. Such a trimer was not even included in the older theory, Twarock says.

She notes that all the structures predicted by Caspar and Klug fall into a subset of the structures that her more-encompassing theory predicts. With the new approach, “you arrive at mathematical structures that are richer and richer,” Twarock says. “Suddenly, you find that nature also uses these structures.”

Bruinsma says, “She [Twarock] has shown very nicely how the Caspar-Klug crystallography fits into a more general crystallography.”

Examining subtler capsid traits, Twarock and her colleagues have identified several instances in which the older theory accurately predicts the sizes and locations of capsomers but not the orientations of their protein constituents.

“This subtlety is really important,” Twarock says.

Consider, for instance, bacteriophage HK97. If the virus actually manifested the capsomer orientations dictated by Caspar-Klug theory, its constituent proteins would be out of whack by angles of 30 degrees or more from where they’ve been observed, Twarock and Roger W. Hendrix of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine have determined. The new tiling theory yields the correct orientations, Twarock says.

Mortal combat

The theoretical advances of the UCLA researchers and Twarock are providing insights that may prove useful for battling viruses.

In the UCLA study, for instance, the scientists added an exercise to their simulations in which they inflated their capsomer-enclosed spheres until the armor plating burst. “It’s sort of like blowing up a balloon and seeing where it pops,” Nelson says.

In some cases, the capsid cracked. In others, it spat out a pentamer. The latter type of breakage has been observed in some viruses, suggesting that the new computer model may offer a way to study breakdown mechanisms, the UCLA team proposes.

“It’s important to know where there might be chinks in the armor,” says Nelson.

In new studies investigating viral-capsid assembly, Twarock is collaborating with Thomas Keef of the University of York and Anne Taormina of the University of Durham, both in England, and Cristian Micheletti of the International School for Advanced Studies in Trieste, Italy. This work applies the information from tiling theory about the types and locations of bonds expected between capsid proteins.

Starting with a new, more-encompassing theoretical description of a capsid, the team dices that virtual structure into various capsomers and notes what types of bonds would have been severed were a real capsid diced up the same way. Then, the researchers simulate myriad ways in which those capsomers might link into intermediate structures while reconstituting the original capsid.

For SV-40, the team has found hundreds of such pathways that collectively include more than 500 intermediate structures.

For each intermediate, the scientists assess the structure’s energy content and its symmetries as a guide to how likely it is to form. “That gives us clues to what drives assembly and how we can prevent it,” for instance, by designing drugs that thwart formation of the most likely intermediates, Twarock says.

“Just figuring out how capsids assemble is incredibly valuable,” says biophysicist Adam Zlotnick of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center in Oklahoma City. And it’s not just medical applications that he has in mind.

There’s also an engineering motive, Zlotnick says. The power to divert the assembly process into new paths might yield useful nanoscale containers and other structures (SN: 1/17/04, p. 46: Available to subscribers at Nanowires grow on viral templates). Artificial viral shells, for instance, might serve as minute containers for substances ranging from catalysts for the chemical and drug industries to magnetic particles for storing digital data.