LISTENING IN A tiny jumping spider (Phidippus audax) may hear airborne sounds from several meters away, new experiments show.

G. Menda, Hoy Lab at Cornell

Accidental chair squeaks in a lab have tipped off researchers to a new world of eavesdroppers.

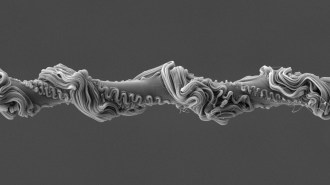

Spiders don’t have eardrums, though their exquisitely sensitive leg hairs pick up vibrations humming through solids like web silk and leaves. Biologists thought that any airborne sounds more than a few centimeters away would be inaudible. But the first recordings of auditory nerve cells firing inside a spider brain suggest that the tiny Phidippus audax jumping spider can pick up airborne sounds from at least three meters away, says Ronald Hoy of Cornell University.

During early sessions of brain recordings, Hoy’s colleagues saw bursts of nerve cell, or neuron, activity when a chair moved. Systematic experiments then showed that from several meters away, spiders were able to detect relatively quiet tones at levels comparable to human conversation. In a hearing test based on behavior, the spiders also clearly noticed when researchers broadcast a low droning like the wing sound of an approaching predatory wasp. In an instant, the spiders hunkered down motionless, the researchers report online October 13 in Current Biology.

Jumping spiders have brains about the size of a poppy seed, and Hoy credits the success of probing even tinier spots inside these (anesthetized) brains to Cornell coauthor Gil Menda and his rock-steady hands. “I close my eyes,” Menda says. He listens his way along, one slight nudge of the probe at a time toward the auditory regions, as the probe monitor’s faint popping sounds grow louder.

Story continues after video

SCARY NOISES In a test of hearing airborne noises, a small dark jumping spider stops moving abruptly (red pointer appears) when researchers broadcast a tone similar to the scary droning of the wings of a predatory wasp. G. Menda, Hoy Lab at Cornell |

When Menda first realized the spider brain reacted to a chair squeak, he and Paul Shamble, a study coauthor now at Harvard University, started clapping hands, backing away from the spider and clapping again. The claps didn’t seem earthshaking, but the spider’s brain registered clapping even when they had backed out into the hallway, laughing with surprise.

Clapping or other test sounds in theory might confound the experiment by sending vibrations not just through the air but through equipment holding the spider. So the researchers did their Cornell neuron observations on a table protected from vibrations. They even took the setup for the scary wasp trials on a trip to the lab of coauthor Ronald Miles at State University of New York at Binghamton. There, they could conduct vibration testing in a highly controlled, echo-dampened chamber. Soundwise, Hoy says, “it’s really eerie.”

Neuron tests in the hushed chamber and at Cornell revealed a relatively narrow, low-pitched range of sensitivity for these spiders, Hoy says. That lets the spiders pick up rumbly tones pitched around 70 to 200 hertz; in comparison, he says, people hear best between 500 and 1,000 Hz and can detect tones from 50 Hz to 15 kilohertz.

“There seems to be no physical reason why a hair could not listen,” says Jérôme Casas of the University of Tours in France. When monitoring nerve response from hairs on cricket legs, he’s tracked airplanes flying overhead. Hoy’s team calculates that an 80 Hz tone the spiders responded to would cause air velocities of only 0.13 millimeters a second if broadcast at 65 decibels three meters away. That’s hardly a sigh of a breeze. Yet it’s above the threshold for leg hair response, says Friedrich Barth of the University of Vienna, who studies spider senses.

An evolutionary pressure favoring such sensitivity might have been eons of attacks from wasps, such as those that carry off jumping spiders and immobilize them with venom, Hoy says. A mother wasp then tucks an inert, still-alive spider into each cell of her nest where a wasp egg will eventually hatch to feed on fresh spider flesh. Wasps are major predators of many kinds of spiders, says Ximena Nelson of the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand. If detecting their wing drone turns out to have been important in the evolution of hearing, other spiders might do long-distance eavesdropping, too.