Large blooms of plankton often appear in ocean eddies, temporary swirls that sometimes bring cool, nutrient-rich water to the surface. When those organisms die, the carbon they contain has to go somewhere, but new studies suggest that very little of it sinks to the ocean floor and gets locked away in sediments. The new data might quash hopes that fertilizing the ocean surface could pull enough carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to substantially affect climate.

Scientists find a larger average concentration of organic matter in deep ocean waters than can be explained by biological productivity at the sunlit surface above. To balance the budget, some researchers have pointed to the immense biomass generated in large ocean eddies (SN: 6/14/03, p. 375: Available to subscribers at Oceans Aswirl), much of which has been presumed to eventually fall to the ocean floor.

Compared with the waters around them, eddies can be productive indeed, says Dennis J. McGillicuddy Jr., an oceanographer at the Woods Hole (Mass.) Oceanographic Institution. In 2004 and 2005, he and his colleagues collected data from eddies in the North Atlantic. For some samples, the researchers estimate that each liter contained about 8,000 colonies of the Chaetoceros diatom, each of which held around 15 cells. Long-term studies in the area suggest that the concentration of Chaetoceros in water outside eddies typically ranges between 1 cell and 10 cells per liter, he notes.

The water hundred of meters below those eddies is low in oxygen but high in carbon, McGillicuddy’s team found. That suggests that much of the eddy-produced organic matter decomposes and dissolves as it sinks, so it doesn’t end up locked away for eons in ocean sediments, says McGillicuddy. Instead, the carbon stays in deep water for no more than a few millennia, a temporary removal that wouldn’t have much effect on climate. McGillicuddy and his colleagues report their findings in the May 18 Science.

Another study reported in that journal suggests that in some cases, eddy-produced organic matter doesn’t even reach deep water. Claudia R. Benitez-Nelson, an oceanographer at the University of South Carolina in Columbia, and her colleagues studied a 200-kilometer-wide eddy that formed west of Hawaii in February 2005. In the 40-km-wide core of that swirl, surface waters were “teeming with life,” she notes.

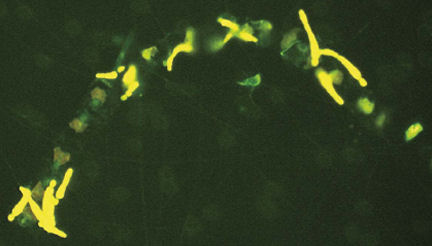

At first, the populations of some diatoms within the eddy were 100 times as great as those found in waters nearby. But within days, diatom numbers within the eddy crashed, probably because the organisms had consumed all the water’s dissolved silica, which they need to build their skeletons. After the population bust, samples of water gathered at a depth of 150 m were full of broken diatom shells that had been stripped of their organic carbon, says Benitez-Nelson. “That was a big surprise,” she notes.

Both teams’ new findings suggest that fertilizing the oceans in the hope of removing large quantities of planet-warming carbon dioxide from the air might not work, says Benitez-Nelson. “Just because there’s a diatom bloom, it doesn’t necessarily mean the carbon is going to go away,” she adds.