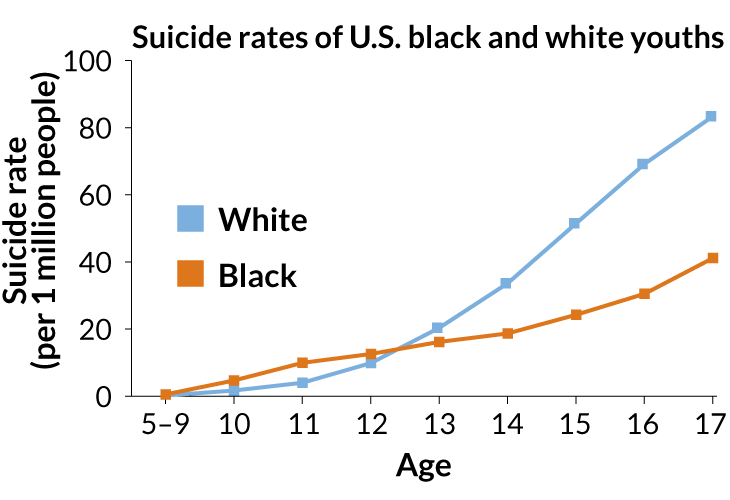

Black children commit suicide at twice the rate of white kids

After age 12, the pattern flips and suicide occurs more frequently among white children

HOW TO HELP New evidence shows that young black kids have higher suicide rates than those of their white peers. Further work is needed to understand why and what preventative efforts could help, researchers say.

Rawpixel.com/Shutterstock