Brain uses decision-making region to tell blue from green

Early visual brain areas, language areas not crucial for color distinction

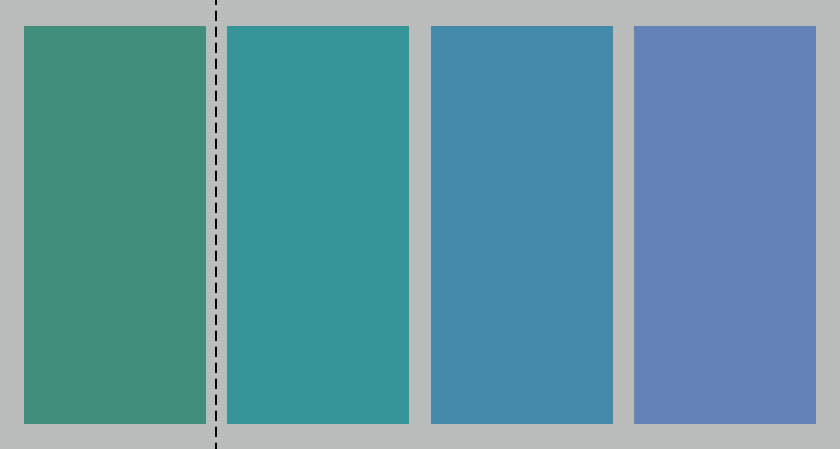

THE BLUES Most people call the color on the left green and the three colors on the right blue. A brain area called the middle frontal gyrus is involved in making this distinction, a new study finds.

C.M. Bird et al/PNAS, adapted by S. Egts