Caught on Tape: Gecko-inspired adhesive is superstrong

As it scurries along the ceiling, a gecko has the sticking power to support not just its own body weight, but about 400 times as much. Besides that sticking power, the natural adhesive on this animal’s feet is clean and reusable, and it works on all surfaces, wet or dry.

Scientists at the University of Manchester in England and the Institute for Microelectronics Technology in Russia have emulated the animal’s adhesive mechanism by creating “gecko tape.” It comes closer to the lizard’s sticking power than any other gecko-styled adhesive so far.

The 1-square-centimeter prototype patch can bear about 3 kilograms, almost one-third the weight that the same area of gecko sole can support.

In the July Nature Materials, Andre Geim of the University of Manchester and his colleagues claim that the tape is scalable to human dimensions: Wearing a “gecko glove,” a person could dangle from the ceiling. In theory, the tape could hold tissues together after surgery or support stunt doubles climbing around movie sets.

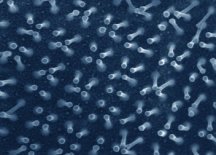

The gecko tape is modeled on the gecko sole, an intricate fingernail-size surface covered with a half-million microscopic, hair-like structures known as setae. Each seta’s tip branches into even finer hairs that nestle so closely with every surface the gecko touches that intermolecular attractions called van der Waals bonds and capillary forces kick in. These bond the gecko’s foot to the surface (SN: 8/31/02, p. 133: Available to subscribers at Getting a Grip: How gecko toes stick).

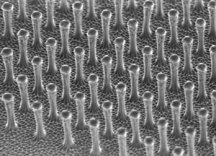

Geim and his team made their synthetic gecko adhesive by fabricating a tidy array of microscale hairs out of polyimide, a flexible and wear-resistant plastic. When mounted on a flexible base, the arrangement and density of the hairs maximize the number of hairs contacting a surface.

“The smaller the hairs are, and the more of them you have, the greater the adhesion,” notes Ron Fearing, an engineer at the University of California, Berkeley.

Unlike a gecko’s feet, however, the tape begins to lose its adhesive power after about five applications. Geim blames this shortcoming on polyimide’s hydrophilicity, that is, its tendency to attract water. With repeated applications, some of the gecko tape’s hairs get soggy, bunch together, and then clump onto the tape’s base. This happens even when the tape is attached to surfaces that are dry to the touch, because they carry a layer of water two or three atoms thick.

By using hydrophilic material, Geim departed from the gecko’s design–its setae are made of keratin, a so-called hydrophobic protein that repels water. Geim says hydrophobic materials, which include silicone and polyester, are more difficult to mold into setae-like structures than is polyimide. Even so, both he and Fearing agree, it will take water-repellant substances to produce a long-lasting gecko tape.

****************

If you have a comment on this article that you would like considered for publication in Science News, send it to editors@sciencenews.org. Please include your name and location.

To subscribe to Science News (print), go to https://www.kable.com/pub/scnw/

subServices.asp.

To sign up for the free weekly e-LETTER from Science News, go to http://www.sciencenews.org/subscribe_form.asp.