What parents need to know about kids in the summer of COVID-19

With the pandemic keeping kids home, it's challenging to study how they spread the coronavirus

As kids get out for bike rides — like this group by the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., on May 28 — and perhaps contemplate more crowded summer plans, scientists still don’t have a full understanding of how effectively children spread the coronavirus.

Sipa USA/Alamy

As states reopen, the coming months bring the prospect of gatherings at pools, playgrounds and even amusement parks. But in this summer of COVID-19, many parents are left wondering what their kids can safely do.

There isn’t a satisfactory answer, because there’s still so much unknown about the coronavirus in regards to children. While studies from China to Italy to the United States have reported fewer confirmed cases of COVID-19 in children than adults and fewer seriously ill children than adults, recent reports of a dangerous inflammatory condition (SN: 5/12/20) illustrate that harms may still emerge.

And concerns about COVID-19 extend beyond kids to their family members and other contacts. If children easily spread the coronavirus between each other and bring it home, they could put relatives at risk and perhaps ignite local outbreaks. At this point, it’s “still unclear whether they contribute significantly to transmission,” says Aubree Gordon, an epidemiologist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. “But they well may.”

Scientists don’t have a full understanding of COVID-19 and children in part because they don’t have a lot of data from places well suited to provide it, such as schools and day care centers. With the pandemic keeping most kids from engaging with their communities as they usually would, we’re left with an incomplete picture of how readily children spread the virus.

But there are studies and reports that have provided clues. This research provides a preliminary snapshot of what the illness means for kids and what we know so far about their role in spreading the infection.

Trustworthy journalism comes at a price.

Scientists and journalists share a core belief in questioning, observing and verifying to reach the truth. Science News reports on crucial research and discovery across science disciplines. We need your financial support to make it happen – every contribution makes a difference.

Children are getting sick less often than adults

Much remains unknown about why COVID-19 can be devastating to some healthy adults and children. But at this stage, studies report relatively few cases of severe illness in kids. “Children overall are doing much better and are less sick than adults,” says Samuel Dominguez, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora.

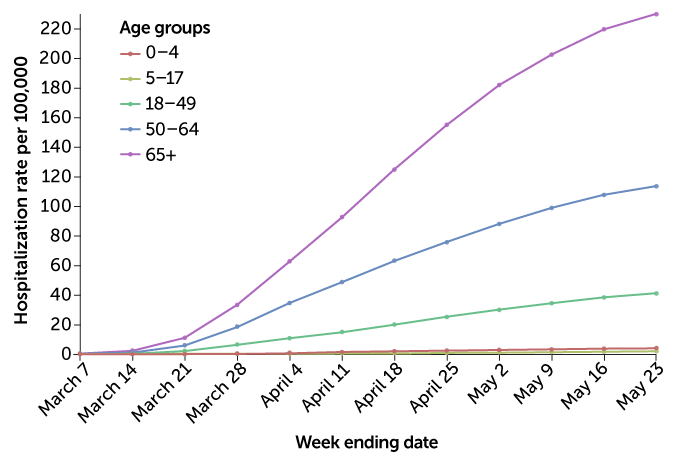

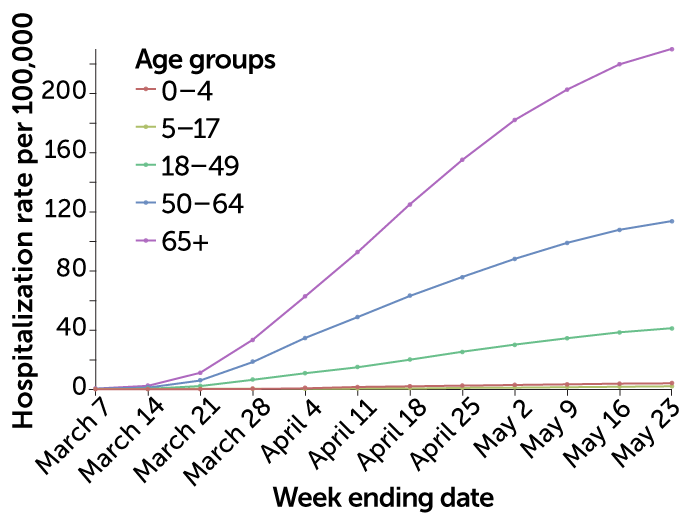

A study from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that of close to 150,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 as of April 2, just over 2,500, or 1.7 percent, occurred in those under the age of 18; that group of children accounts for 22 percent of the U.S. population. The researchers had hospitalization information for 745 of the children’s cases: 147 had been admitted to hospitals, with 15 in intensive care. Three children died, the researchers reported in the April 10 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. CDC data as of May 23 continues to show a much higher hospitalization rate for COVID-19 in adults than in children.

Age brackets

In the United States, adults continue to be hospitalized due to COVID-19 at a much higher rate than children, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

U.S. COVID-19 hospitalizations by age group

Source: CDC

But word of a dangerous, excessive immune response in some children that may be linked to a SARS-CoV-2 infection renewed fears. Eight children with persistent fever and gastrointestinal symptoms required intensive care in London in mid-April. The children, one of whom died, had tested positive for antibodies to the coronavirus, the study authors reported online May 7 in the Lancet. A positive antibody test is evidence of a prior infection (SN: 4/28/20). Days later, also in the Lancet, doctors from the hard-hit Bergamo province in Italy reported similar symptoms in 10 children, eight of whom had evidence of antibodies to the coronavirus.

As of June 1, New York state’s Department of Health is investigating 189 cases of the inflammatory syndrome. Washington, D.C., and a growing number of states, including Wisconsin, Louisiana and Florida, also have reported cases. The CDC has released a health alert and case definition for the syndrome, which they’ve named multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, or MIS-C.

The syndrome shares some symptoms with Kawasaki disease, which mainly strikes children younger than 5 and is marked by high fevers, inflammation and sometimes poor heart function. But multisystem inflammatory syndrome is also hitting older children and teens and frequently includes gastrointestinal symptoms not commonly seen with Kawasaki disease.

Researchers theorize that the syndrome is an immune response linked to an infection with SARS-CoV-2, showing up around four weeks later, says Jeffrey Burns, a pediatric critical care specialist at Boston Children’s Hospital. Children becoming critically ill from the syndrome at this point “remains very infrequent,” he says.

It’s not clear why children don’t tend to get as ill with COVID-19 as adults. “I don’t know if that is really a biological or immunological phenomenon or if it’s an exposure phenomenon,” says Dominguez, tied to how quickly schools were closed and children were isolated due to social distancing. “Did we just spare them because they weren’t exposed?”

It’s not clear how much kids contribute to spread

In January, a 9-year-old on a ski holiday in the French Alps with his family was exposed to a traveler with COVID-19. His experience may provide the best-case scenario of what can happen when a child is infected.

After contracting the coronavirus, the child experienced mild symptoms. And despite attending three different schools while ill, he did not transmit the virus to any of the 55 school contacts tested, researchers reported April 11 in Clinical Infectious Diseases. Nor did his two siblings become infected. Yet influenza was spreading between children at the schools and among the siblings at the very same time.

One of the rationales behind the quick closure of schools in the face of COVID-19 was drawn from past experience with children and influenza. Children — particularly young children — are considered the main drivers of flu transmission within communities, and shutting schools has curtailed the spread of the flu during past epidemics and pandemics.

But the role that children play in spreading SARS-CoV-2 is less apparent. The vacationing schoolboy and his classmates may have just been lucky, but there’s other early evidence that children may not be as important to the spread of the coronavirus as they are to influenza.

A peek into schools in Australia early in the pandemic suggests that the virus may not spread wildly among students. In New South Wales, the Australian state that includes Sydney, 18 people from 15 schools — nine students and nine staff — were confirmed with COVID-19 from March 5 through April 3. Even though 735 students and 128 staff were in close contact with the initial 18, only two students appeared to have contracted the coronavirus at school from those first cases.

Ireland reported its first case of COVID-19 — a student who had been to Northern Italy — at the beginning of March; schools closed at the end of the day on March 12. In that time, three students (one without symptoms) and three adult staff with COVID-19 were in contact with 924 children and 101 adults at schools. None of the contacts become infected, researchers report May 28 in Eurosurveillance.

Sweden has kept many schools open during the pandemic, but the country’s Public Health Agency hasn’t released data on how students and teachers have fared. Meanwhile, in Israel, some recently reopened schools have shut again after cases of COVID-19 were reported among some staff and students.

Within the home, studies have suggested adults rather than children are more often the first to get sick in a family. But kids may not be any less susceptible to infection, according to a study in Shenzhen, China of 391 COVID-19 cases and 1,286 close contacts. Children under the age of 10 were as likely to be infected as adults, the researchers reported April 27 in the Lancet Infectious Diseases.

One sticking point in understanding the role children play in the spread of SARS-CoV-2 is that researchers don’t know the extent to which kids can be infected and asymptomatic but still pass the virus along. Studies of adults have found that they can spread the virus if they never have symptoms (SN: 3/13/2020) and before symptoms appear (SN: 4/15/20).

Without widespread testing, it’s hard to pin down the number of children with asymptomatic cases of COVID-19. A few studies have provided estimates. For example, out of 728 confirmed cases in children in China, 94 did not have symptoms, a total of 12.9 percent, according to a study in the June Pediatrics. A smaller study found a higher percentage: Among 36 children up to the age of 16 who were confirmed with the infection as of March 1 in Zhejiang, China, 10 were asymptomatic, or 28 percent, researchers reported in the June 1 Lancet Infectious Diseases. It’s also not clear yet whether asymptomatic kids readily infect others.

It remains possible that children haven’t distinguished themselves as major transmitters of SARS-CoV-2 up to now because they haven’t been interacting as they usually would at schools, day cares and playgrounds. “Certainly children are major spreaders of other kinds of viruses,” says infectious disease pediatrician and vaccine researcher Kathryn Edwards of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville. “So that’s what’s so curious.”

What happens over the summer may fill in some blanks

Countries around the world have begun to reopen some of their schools, with modifications such as smaller class sizes, socially distant seating and frequent handwashing breaks. The experiences of school systems abroad may provide more data as U.S. officials consider plans to reopen schools here.

Those plans will proceed without a vaccine. Promising candidates will need to be studied in children to make sure they are safe and effective for younger ages. Current vaccine trials are being conducted in adults (SN: 5/20/20), although the University of Oxford has announced plans to begin testing their COVID-19 vaccine in children.

That leaves officials as well as parents waiting for more research, testing and contact tracing (SN: 4/29/20) to reveal more about the virus’ spread and its impact on children. Until then, it will remain challenging to decide what’s safe for kids during the summer of COVID-19.