Treatments that target the coronavirus in the nose might help prevent COVID-19

Scientists and doctors want to interrupt the virus before it settles in

Nasal swabs are one of the main ways to test for an infection with coronavirus that causes COVID-19. Scientists are now exploring ways to stop the virus in the nose, before an infection takes hold.

Zstockphotos/iStock/Getty Images Plus

COVID-19 can ravage the body, targeting the lungs, heart and blood vessels. To curb this wide-ranging attack, scientists are focusing on another part of the body: the nose.

The virus that causes the illness, SARS-CoV-2, gains its foothold by infecting certain nasal cells, studies suggest (SN: 6/12/20). As a result, the nose has emerged as a key battleground in the war against COVID-19. Slowing or stopping that nasal invasion might ultimately be powerful enough to change the course of the pandemic, some scientists suspect.

So far, no such therapies exist. But people who study the nose and its contents bring fresh perspectives about the early stages of COVID-19 infections. Scientists are developing and testing ways to prevent the virus from settling in to prime nasal real estate. These include a nose spray that smothers and inactivates a key viral protein, disinfectants that are commonly used before sinus surgeries, and even dilute baby shampoo misted up the nose.

“I’m a nose person,” says Andrew Lane, an otolaryngologist and rhinology specialist at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. But to most people, noses don’t usually spark a lot of interest, he says. “Now it’s the center of people’s attention.”

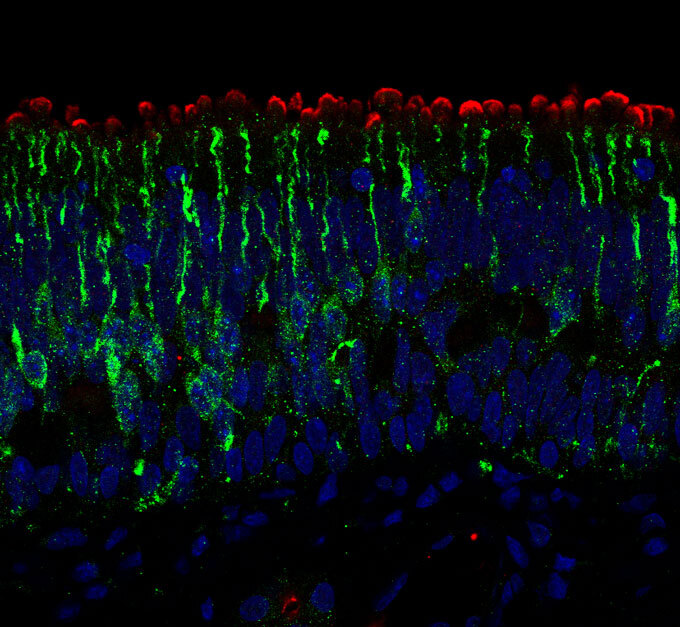

This nasal gazing makes perfect sense. “The nose is a place where the virus is setting up shop,” Lane says. In a recent study, he and colleagues measured levels of a protein on human cells called ACE2 that’s thought to be one of the ways the virus can infect the cells. Among a collection of human tissues taken from the noses and throats of people, the upper back part of the nasal cavity, known as the olfactory epithelium, was packed with ACE2. (This spot is also where smell cells dwell; SARS-CoV-2 infections there have been linked to loss of smell (SN: 5/11/20).

“You would just see this incredibly bright signal coming from the olfactory epithelium,” Lane says. That ACE2 signal suggests that those cells might be key entry ports that allow the virus to move into the rest of the body, and even perhaps back out again to infect other people, the researchers report in the Sept. 1 European Respiratory Journal.

To interrupt the infection in the nose, some scientists are turning to specialized immune proteins found in camels, llamas and alpacas. Called nanobodies, these proteins help fight off invaders in the body, but are smaller and thought to be hardier than their human antibody kin. In lab studies of proteins and cells in dishes, biochemist Aashish Manglik and cell biologist Peter Walter, both at the University of California, San Francisco, have shown that custom-designed nanobodies can smother the spike protein that the coronavirus can use to break into cells (SN: 2/3/20).

The researchers haven’t yet tested the nanobodies in people. But their preliminary results suggest that, once neutralized with nanobodies, the virus “cannot enter human cells,” Walter says. “It cannot establish that beachfront in the nasal cavity.” These nanobodies were stable when dried and aerosolized, the researchers found, suggesting that they could be made into a nose spray. The most recent results, which haven’t been peer-reviewed, were posted August 17 at bioRxiv.org. The team hopes to begin tests in laboratory animals and eventually, in humans. Walter and Manglik hold patents on the specially designed nanobodies.

A simpler approach would be to wash away or kill the virus in the nose. Some doctors have begun looking at iodine — the basis of a common antiseptic that can treat wounds and disinfect skin before surgeries. In a June 10 review article in Ear, Nose & Throat Journal, researchers describe evidence that suggests a dilute solution called povidone-iodine might safely eradicate SARS-CoV-2 in the nasal cavity and throat.

Early hints that this rinse might work come from studies of the virus in lab dishes, including a paper published June 16 in the Journal of Prosthodontics. And a clinical trial is under way at the University of Kentucky in Lexington with health care workers using povidone-iodine nose sprays and gargles preventively before, during and after shifts.

Other researchers are turning to an even more low-tech solution: a mixture of soap and salt. Saline rinses can remove bacteria and allergens from the nasal cavity and ease symptoms of allergies, sinus infections and colds. A current clinical trial is designed to look for effects of baby shampoo mixed with a salt solution on the symptoms and possible spreading of SARS-CoV-2 in people who have COVID-19. The soapy solution might be able to wash viruses out of the nose, or pop their protective outer layer and inactivate them, says Justin Turner, a nasal and sinus surgeon and rhinologist who is among the researchers running the trial at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

“We know that the virus is very sensitive to soaps and surfactants,” Turner says. Washing hands with soap, for example, is a good way to eliminate the coronavirus. “It seems like it could be reasonable to recommend that for the nose as well,” Turner says.

During the trial, COVID-19 patients with mild to moderate symptoms, but not sick enough to be hospitalized, will either do nothing special to their nose, rinse it with saline several times a day or rinse it with saline plus a small amount of baby shampoo. In the clinical trial, which began May 1, Turner and colleagues are tracking around 100 people’s symptoms and the amount of virus in their noses, a measurement that might indicate whether someone is more or less contagious. An early look at 45 patients shows that people who did the nose rinses, either saline alone or saline with soap, got rid of their headaches and nose congestion about a week earlier than the people who didn’t use rinses. Those interim results appear online September 11 in the International Forum of Allergy & Rhinology.

It’s possible that nose rinses might “stir up the virus and facilitate its spread,” Lane cautions. But the idea of a nose rinse holds promise, and is worth testing, he says. This work, and other studies that target the nose are gaining momentum. “Everybody is thinking the same way, and I think there’s a lot of merit to it,” Lane says. “Nip it in the bud, and stop it before it gets a hold.”

Sign up for our newsletter

We summarize the week's scientific breakthroughs every Thursday.