When researchers expand their studies of infant motor development to include children from diverse cultures outside of North America, like this boy from Azerbaijan, they learn that development norms are too narrow.

Anthony Asael/Alamy Stock Photo

For generations, farther back than anyone can remember, the women in Rano Dodojonova’s family have placed their babies in “gahvoras,” cradles that are part diaper, part restraining device. Dodojonova, a research assistant who lives in Tajikistan, was cradled for the first two or three years of her life. She cradled her three children in the same way.

Ubiquitous throughout Central Asia, the wooden gahvora is often a gift for newlyweds. The mother positions her baby on his back with his bottom firmly over a hole. Underneath is a bucket to capture whatever comes out. She then binds the baby with several long swaths of fabric so that only the baby’s head can move. Next, she connects a funnel, specially designed for either boys or girls, to send urine out to that same bucket under the cradle. Finally, she drapes heavy fabric over the handle atop the gahvora to protect the child from bright light and insects.

Babies stay in that womblike apparatus for hours on end, with use decreasing as the child ages. When babies fuss, mothers often shush them by vigorously rocking the cradle back and forth or leaning over the side to breastfeed. Besides keeping babies dry and warm, gahvoras provide a sense of safety, Dodojonova says. “It is very nice for children because they are bound and cannot move.” Eventually, they are running and jumping like children everywhere.

To the uninitiated, this child-rearing approach may sound odd, or even shocking. Yet cultures should be viewed within their own context, says psychologist Catherine Tamis-LeMonda of New York University. “We engage in practices that fit our needs, our own everyday lives.”

Though Central Asia is home to 73 million people, Western researchers such as Tamis-LeMonda have only recently begun to document the gahvora’s use and possible impact on how children grow.

Ignoring cultural variation of this sort leaves a big blind spot in the science of child development. Western researchers and medical staff define “normal” development — in this case, how and when babies acquire motor skills such as sitting, crawling and walking — based on a century of research on mostly white, Western babies.

Now a few motor development experts are pushing back with a new line of thinking that traces back to the 1950s, when evidence for huge variations in how and when babies acquire motor skills began to emerge in a piecemeal way. At that time, anthropologists and cultural psychologists working in far-flung locales started documenting how babies in different cultures move about.

In recent decades, that research has become more systematic. Scientists are comparing the motor skills of babies in various cultures and creating controlled experiments to see if training can speed up the development of certain skills.

And motor skills don’t arise in isolation. When a baby begins to sit, crawl or walk, she gains a new view on the world, which alters her perception. It also influences how babies and caregivers communicate. A baby who has learned to walk, for instance, will often carry objects to her mother, who frequently responds with words or ways of speaking that are new to the baby. So researchers are also studying how culture influences other areas of development linked to motor skills.

This research is “not just about walking,” says Lana Karasik, a developmental psychologist at the City University of New York’s College of Staten Island. “It’s about what walking gives babies.”

As this work continues among broader populations, it’s becoming clear that across continents and cultures, children with the ability to do so will learn to walk. For some babies, that tentative first step may occur at 8 months old; for others, age 2 or 3 is a perfectly good time to start exploring.

The rule book

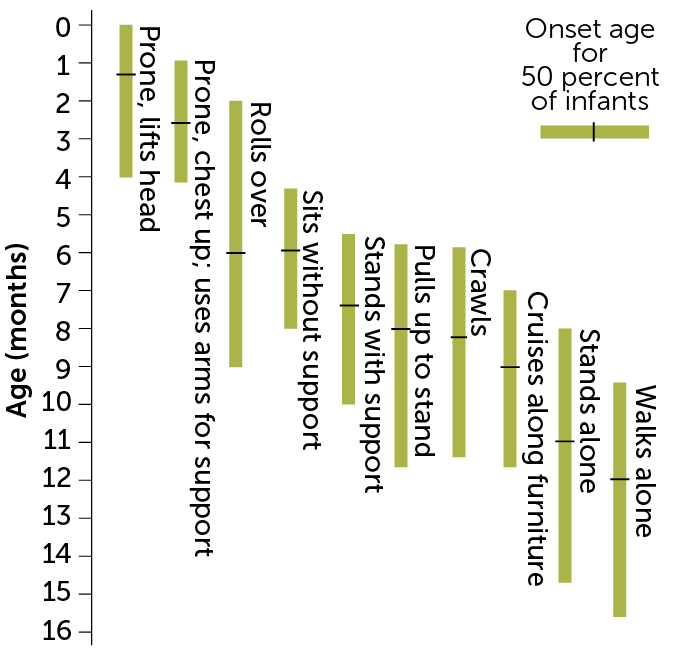

Many parents in Western cultures are familiar with infant motor development charts. Three-month-olds might be shown lifting their heads, 6-month-olds are sitting and 12-month-olds are walking. The implication is that babies learn to get around on a relatively fixed timeline, regardless of environment or experience.

Such charts trace their origins to the early 1900s, when developmental psychologist Arnold Gesell of Yale University began filming babies from behind a one-way mirror. Based on 12,000 recordings, Gesell outlined in 1928 a developmental schedule for babies from 3 to 30 months old.

Meanwhile, psychologist Nancy Bayley began a study tracking development in more than 60 white babies born to relatively affluent families in Berkeley, Calif., in the late 1920s. That decades-long project, known as the Berkeley Growth Study, prompted Bayley to develop a way for a nonfamily member to assess a child’s development, including motor skills. She rolled out the Bayley Scales of Infant Development in 1969. Researchers and clinicians still widely use those scales, now in their fourth iteration.

Gesell, Bayley and others thought that babies began to move when their bodies matured enough to do so, and that motor skills emerged along a linear path, with sitting coming before crawling and crawling before walking. But that thinking hinged on a small set of U.S. babies.

In the early 2000s, the World Health Organization sought to broaden research on motor development to include the rest of the world. WHO researchers measured motor skill acquisition from 4 months to age 2 among 816 babies from five countries: Ghana, India, Norway, Oman and the United States. The analysis, appearing in 2006 in Acta Paediatrica, outlined windows of development during which certain motor skills should arise. Failure to achieve those skills within given windows — 8 to 18 months for walking independently, for instance — was considered “evidence of abnormal growth.”

Unfortunately, the WHO relied on Bayley’s motor scale, which meant the study used white U.S. babies as the standard of comparison. Also, the research lacked babies from cultures where scientists have documented accelerated or uneven patterns of motor development, including the many cultures of Central Asia.

When “norms” based on a narrow sample of babies get built into a model and then that model is applied to a different, but still narrow, sample of babies, the whole system falls apart, says Karen Adolph, a psychologist at NYU. “Do you really want to say a third of the world is delayed and another third of the world is accelerated and our part of the world is normal?”

The need to look beyond the United States was driven home for Adolph several years ago, when she heard from a woman at Procter & Gamble who had been tasked with selling diapers throughout Central Asia. Sales, the woman said, were abysmal. It seemed the gahvora was to blame.

Adolph relayed the story to her graduate student Lana Karasik, who was studying motor development across cultures. Karasik replied that her husband’s family is from the region. “I know that practice,” she said. So several months later, in early 2014 and in collaboration with UNICEF and Save the Children, Karasik, Adolph and Tamis-LeMonda launched a study of motor development in babies in Tajikistan.

Culture clash

As Gesell and Bayley were building their models of motor development, other researchers had begun to document deviations from those standards. Charles Super, a developmental psychologist at the University of Connecticut in Storrs, recalls reading a paper from a researcher studying Ugandan infants in the 1950s. Ugandan babies walked much earlier than babies in the West. The researcher wrongly interpreted that difference as an inferiority, suggesting that fast development would mean intellectual stunting, Super recalls. “I didn’t like that argument.”

In the 1970s, Super moved to Kenya with his wife, an anthropologist. He began investigating motor development among babies born in a farming community known as Kokwet. Between 1972 and 1975, he documented when those babies acquired new motor skills using the Bayley scale and interviewed mothers about their child-rearing practices.

Kokwet babies sat, stood and walked about a month earlier than Western infants, Super reported in 1976 in Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. But the babies were slower to master other skills, such as lifting their heads, rolling over and crawling.

Super observed that mothers wore their babies on their backs while laboring in the fields. He suspected that vigorous motion gave the babies the sort of constant exercise needed to help develop strength and agility. The mothers also told Super they actively trained their children to walk through exercises like air stepping.

“The parents had a theory: If you don’t teach your children to walk, they won’t walk,” Super says. At the same time, however, mothers sought to keep their babies from crawling given myriad dangers on the ground, such as open fire pits and snakes. The training combined with the restrictions probably explains the development patterns that Super observed that were outside of normal ranges. His findings agreed with observations made elsewhere.

For instance, anthropologist Alma Gottlieb’s research on the Beng people in Ivory Coast from the late 1970s to the early 1990s showed that Beng babies sit earlier than Western babies but are actively discouraged from walking before age 1. The Beng believe that early walking can cause a grandparent’s early death, says Gottlieb, a visiting scholar at Brown University in Providence, R.I. And keeping the babies close and happy discourages the little ones from returning to a previous life.

When German psychologist Heidi Keller used Bayley’s rubric on the Nso people in Cameroon in the 1990s and 2000s, she found their motor skills were mostly advanced compared with German babies. She attributed the difference to the fact that Nso babies are in constant contact with caregivers and provided with regular exercise and massage. “Every culture emphasizes the domains of development that are considered important,” Keller says.

Motor skills can be acquired “out of order” and selectively accelerated or decelerated through cultural practices, research by Super, Gottlieb, Keller and others have shown.

In recent years, researchers have conducted experiments to see if training can accelerate motor skill development. At a public pool in Reykjavík, Iceland, one dynamic swim instructor taught a dozen 3- to 5-month-old babies to stand atop a hand or board — well in advance of the 9-month “norm” for standing, researchers reported in 2017 in Frontiers in Psychology.

One natural, unintended experiment came from advice from the American Academy of Pediatrics in the 1990s. To reduce the risk of sudden infant death syndrome, or SIDS, which is more likely to occur in babies who sleep on their bellies, the academy suggested that babies be placed on their backs to sleep. But back sleeping delayed when those infants developed the abilities to roll, sit, crawl and stand. Importantly, studies looking into the delay found that these babies eventually caught up to their stomach-sleeping peers. Just in case, the academy now recommends daily tummy time, where babies play on their stomachs to build strong muscles.

Cradled and bound

Rugged, mountainous Tajikistan is bordered by China, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the country experienced a civil war. Today, infrastructure remains poor, with snow and flooding making the winding, mountain roads impassable for much of the year. Those logistical challenges have limited Karasik’s research to the capital city of Dushanbe and surrounding villages. She travels with behavioral scientist Scott Robinson, who got involved with the work while spending a semester in Adolph’s lab.

Karasik, a Belarusian refugee who moved to the United States in 1989 at age 10, is well-suited to working in Tajikistan. She can communicate in Russian, which many Tajiks still speak, fostering a level of trust in Karasik not often afforded to outsiders. She has also recruited Dodojonova and other local Tajik women to run her project while she’s away.

With so little known about gahvora cradles, especially in rural areas, Karasik’s first order of business was to document Tajik life. In the villages Karasik and her team visited, families live in one-room clay huts and share labor and child-care duties with neighbors. Almost half the fathers work as laborers in Russia and are absent for extended periods; the rest work odd jobs or are unemployed. Electricity tends to work for only two hours in the morning and two at night, during which time families watch television and eat dinner. The gahvora is placed in the center of the room.

Karasik’s team measured gahvora use through videos and interviews with mothers. All but three of 185 mothers interviewed used a gahvora, the team reported in October 2018 in PLOS ONE. Newborns spent anywhere from 8.5 to 23 hours a day in the cradle; 2-year-olds spent two to 14.5 hours. About 40 percent of mothers breastfed babies while leaning over the gahvora, and 83 percent of the moms engaged in vigorous rocking that lasted anywhere from about four to 22 minutes at a time.

In July 2018, Karasik presented unpublished research in Philadelphia at the International Congress of Infant Studies showing that Tajik babies hit motor skill milestones months later than babies in the WHO study. For instance, at 1 year of age, almost all infants in the WHO sample were crawling and half were walking. At age 1, just 62 percent of Tajik babies are crawling and 9 percent are walking. Using WHO standards, almost half of all Tajik babies would be diagnosed with motor delays, Karasik says.

But Tajik babies seem to catch up to their Western peers by about age 4 with no discernible long-term repercussions, data collected by Karasik show. What Karasik really wants to understand moving forward is how being bound for such long stretches during those early formative years affects other areas of development and even babies’ temperaments.

Walking and talking

The idea that the acquisition of a new motor skill triggers other skills is known as the developmental cascade. When a baby acquires a new way of getting around, the child’s vantage point changes, along with interactions with caregivers and the ability to explore the environment, says Eric Walle, a developmental psychologist at the University of California, Merced. Walle is particularly interested in the link between walking and language.

After discovering that babies who can walk have larger vocabularies than infants who are still crawling, Walle decided to see what would happen to language skills if he tweaked when babies learned to walk. But “you can’t really experimentally manipulate walking onset,” he says.

So Walle did the next best thing. He took his research to Shanghai, where babies typically walk about six weeks later than U.S. babies. That difference may be because babies in urban China live in more cramped environments and have less opportunity to move around than U.S. babies.

He compared the language skills of 40 12.5-month-old U.S. babies with 42 Chinese babies, ages 13 to 14.5 months old. Both groups were almost evenly split between walkers and crawlers. His analysis, appearing in 2015 in Infancy, showed that the same divergence in language abilities seen between walking versus crawling American infants also occurs in Chinese babies. In other words, language skills emerge alongside the ability to walk.

“Even though these kids were walking later, growing up in a very different culture, and exposed to a very different language, they were showing a similar difference,” Walle says. “Walking shakes up the system.”

A child’s view

Karasik is keen to see if the gahvora influences how Tajik babies think. Testing that link in a remote region with a dodgy supply of electricity has proved challenging, though. For instance, eye trackers are often used to study how infants view the world around them. But typical eye trackers are designed to be stationary, which means they’re heavy and expensive.

Enter visual perception researcher Kirsten Dalrymple of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. Her team has developed a portable eye tracker that runs on batteries, useful for remote villages. Dalrymple also had some idea about the areas of development to focus on, such as the ability to match sights and sounds, which in U.S. babies has been shown to develop alongside motor ability.

“Our brains have to learn: ‘Hey, every time I clap my hands together, this noise comes out.’ That’s not something we’re born with,” Dalrymple says.

Karasik and Dalrymple began by gauging when American babies develop that ability. Babies come into the lab, and the eye tracker sits on a nearby table, where it uses a camera to measure reflections coming off the eye. On a computer screen synced to the tracker, two cartoon animals jump up and down, but only one is paired with a “doink” sound.

When a baby’s eyes focus only on the animal making noise, researchers interpret that as the baby correctly pairing sights and sounds. An unpublished pilot study of 30 babies in Minnesota suggests that pairing ability appeared at an age of around 9 months in those babies.

In January, Karasik traveled to Tajikistan and trained Dodojonova to use the portable eye tracker. If perception and action are linked, and Tajik babies’ motor development is delayed relative to Western babies, then the ability to link sights and sounds should also be delayed. The researchers are analyzing their data now.

Karasik and her colleagues also hope to start collecting data on Tajik babies’ temperaments, which in infants is thought to manifest as individual differences in reacting to events and regulating emotions. Does restriction in a gahvora change how Tajik babies respond to people around them or behave outside the gahvora? “Even if babies are out, they may not be taking the opportunity to move,” Karasik says.

She plans to administer a standard temperament survey that asks moms to answer questions over a weeklong period and covers issues such as “How often does your baby play with a single toy or object for five to 10 minutes?” and “How often does your baby fall asleep within 10 minutes?”

The team suspects the gahvora teaches babies restraint. Back when the project first started, Tamis-LeMonda recalls, the researchers wanted to record babies’ cries as they were put into the gahvora — an idea that was soon scrapped. The babies didn’t fuss or cry.

The idea that the gahvora builds traits like patience and mindfulness resonates with Dodojonova, who has become one of the cradle’s staunchest advocates. In recent years, she has taken to writing pamphlets calling on mothers to continue cradling. The practice is under threat, she says, from disposable diapers, which are now widely available, and Tajik pediatricians who embrace Western notions that are at odds with cradle use, such as tummy time and breastfeeding in the mother’s arms.

The gahvora teaches children that “they cannot do everything that they want,” Dodojonova says. What parent wouldn’t wish for that?