BIG FISH A fish called an opah, studied here by researchers, is now proposed to be as about as close to a full-body warm-blooded fish as science has yet discovered.

NOAA Fisheries West Coast/Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

A fish that looks like a giant cookie with skinny red fins comes the closest yet among fishes to the whole-body warm-bloodedness of birds and mammals.

The opah (Lampris guttatus) has structures never before recognized in fish gills that may help conserve the warmth in blood, says Nick Wegner of the Southwest Fisheries Science Center in La Jolla, Calif. The unusual gills and other heat-saving features don’t achieve the high, stable body temperatures that define warm-blooded, or endothermic, mammals and birds. But measurements suggest that the opah can keep its heart and some other important tissues several degrees warmer than the deep, cold water where it swims, Wegner and his colleagues say in the May 15 Science.

Fishes as a rule stay the temperature of the water around them. But biologists have found exceptions called regional endotherms, which can maintain warmth in certain tissues. Such ocean athletes as tunas and lamnid sharks, for instance, preserve warmth in muscles that power their swimming. And billfishes, among others, keep their eyes and brains warm. But all of these regional warmers still have to cope with hearts that eventually cool and slow when the fish do long dives into cold depths.

Slowing the heart delays the delivery of oxygen to muscles and other tissues. A cold heart “affects everything,” says ecophysiologist Diego Bernal of the University of Massachusetts in Dartmouth, who wasn’t part of the research.

Previous work had hinted the opah might be able to keep its eyes and brain warm. But finding the opah’s warm heart is “the really, really interesting part,” Bernal says. “We have all these big fish out there that we love to eat, love to catch, but we know almost nothing about their basic biology.”

The first evidence for a warm heart and circulatory system came from Wegner, a self-described “gill guy.” Wegner wasn’t expecting anything unusual when he received some gill specimens. The gills “sat in a bucket of formaldehyde for several months,” he says. But as soon as he saw the tangled masses of blood vessels in the gills, he suspected they were for conserving heat.

Story continues below graphic

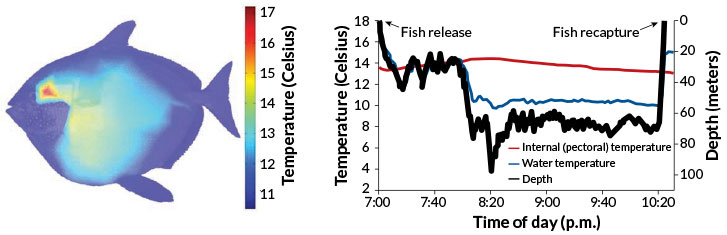

KEEPING WARM On a silhouette of an opah (left), the warmer colors indicate higher internal temperatures measured several centimeters below the skin. In a separate study, temperature recorders attached to the muscles of an opah allowed to dive on its own for more than three hours show stability in muscle temperature despite plunges into the cold depths (right). Credit: N.C. Wegner et al/Science 2015

To sort out the complex pattern of blood flow in a mass of vessels, Wegner injected a blue substance from one end and a red one from the other. Blue and red flowed toward each other creating alternating bands as in a countercurrent heat exchanger. That suggested that blood warmed by passing through the body took the chill off nearby vessels carrying blood that had just picked up oxygen from cold seawater swishing through gills. The circulatory system was saving its heat, Wegner says.

Temperature measurements from fish supported the idea. In about 20 freshly caught opah, temperatures in the heart, visceral organs, head and pectoral muscles were about 3 to 6 degrees Celsius higher than the fish’s surroundings. The researchers then attached temperature-logging devices to the pectoral muscles of four opah and released them for a swim. Muscle temperatures averaged about 5 degrees Celsius above the seawater’s.

Pectoral muscles work a lot in the opah, warming blood that eventually flows through the gill heat exchanger. Unlike many fishes, opah don’t rely on undulating their tails or bodies for steady travel. Instead, the big pectoral muscles make those skinny little pectoral fins flap, flap, flap.

Tagging studies show opah spend more time in deep, cold water than albacore tuna, which don’t have a heart-warming gill system. That behavioral comparison itself suggests enhanced endothermy for opah, says physiologist Robert Shadwick of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, who wasn’t part of the study. The power to maintain some body heat could help explain how opah flourish in deep water.