Distant planets’ atmospheres revealed

Telescopes get best glimpse of gases on exoplanets

Alien worlds have become a little less alien. Astronomers have gotten the most detailed look yet at the atmosphere of a planet outside the solar system.

The study is among the first to directly analyze the chemical makeup of an exoplanet. In the past, astronomers inferred the existence of exoplanets and their gases by looking for subtle changes in the light streaming from the planet’s star. Now, with improved instruments, a team led by Quinn Konopacky of the University of Toronto has detected light coming directly from a planet light-years away.

“It’s [data] I imagined we’d have in 10 years,” says Jonathan Fortney, a planetary scientist at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

The data have high enough resolution to reveal not only the presence but the abundance of carbon monoxide and water in the planet’s atmosphere, the team reported online March 14 in Science. Such information could shed light on how the planet formed. Such studies could also reveal the presence of life on a distant planet, but the planet’s size and orbit have already ruled it out as a habitable world.

“This is the start of a great new era in exoplanet studies,” says Sara Seager, an astrophysicist at MIT.

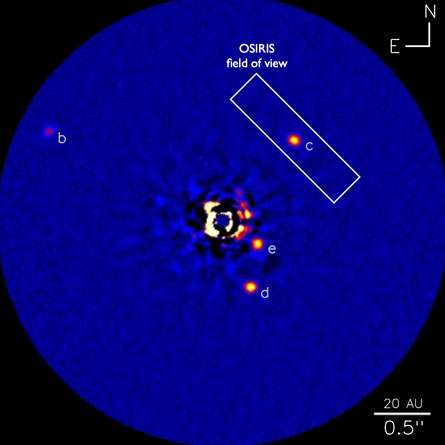

In 2008, Christian Marois of the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory in Victoria, British Columbia, and colleagues took the first image of a multiplanet system outside the solar system, showing three gas giants orbiting the star HR 8799 (SN: 12/6/2008, p. 5). HR 8799 is about 130 light-years from Earth, in the constellation Pegasus. The planets are scorching hot, making them bright enough for astronomers to detect directly. In 2010, the researchers imaged a fourth planet around HR 8799 (SN Online: 12/3/10).

In the new study, Konopacky, Marois and colleagues focused on one of these planets, HR 8799c. Five to 10 times as massive as Jupiter, HR 8799c sits about eight times farther away from its star than Jupiter does from the sun. Because of that great distance, the astronomers could block the star’s light and record infrared light from the planet using the Keck II 10-meter telescope in Hawaii. Because different gases absorb and emit light in distinct ways, the team could identify carbon monoxide and water but found no methane, which scientists had thought might be present.

In another new study, posted online March 11 at arxiv.org and accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal, researchers simultaneously collected infrared light from the atmospheres of all four planets orbiting HR 8799 using the 200-inch Hale Telescope at Caltech’s Palomar Observatory. A team led by Ben Oppenheimer, an astrophysicist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, found hints of ammonia, methane, carbon dioxide and acetylene in the planets’ atmospheres. The chemistry of each planet varies, Oppenheimer says. What’s more, he says, “they’re different from anything in our own solar system.”

Although the teams looked at different wavelengths of light, which pick up different types of molecules, the two studies appear consistent, Oppenheimer says.

But by peering at just one planet, Konopacky’s team obtained more detailed data that allowed the researchers to get a sense of how much carbon and oxygen is in HR 8799c’s atmosphere.

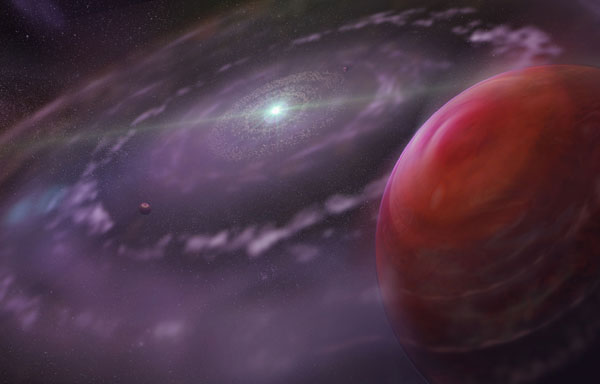

Knowing the ratio of carbon to oxygen in the atmosphere may reveal how the planet formed, Konopacky says. Astronomers have two competing theories of how planets arise from the disk of gas and dust encircling a young star. In the gravitational instability model, some of the gas and dust suddenly clumps and collapses, simultaneously creating a planet’s core and atmosphere. In this scenario, the chemical composition of a planet should match that of its star, she says.

In the other model, known as core accretion, planet building is a two-step process. First, material from the disk accumulates into a core. Later, the core captures gases swirling in the disk to form an atmosphere. In this case, the carbon-to-oxygen ratio of the planet may differ from the star because the accretion of cores may deplete the disk of certain elements, altering the chemical soup from which the atmosphere can later form.

Compared with its star, HR 8799c appears to have slightly more carbon relative to oxygen, suggesting the planet originated via core accretion. Konopacky and her colleagues surmise that when the disk around HR 8799 formed, water froze into particles of ice. The bits of ice collided to form the planet’s core, leaving behind little water vapor, and therefore less oxygen, when the planet accumulated its atmosphere later on.

Other researchers are not convinced by this conclusion. “We don’t really understand planetary formation enough to make a strong case either way,” Fortney says. But the data from both new studies may help astronomers refine their simulations of planetary formation, Oppenheimer adds.

So far, astronomers have directly imaged planets around three distant stars, Seager says, but researchers are poised to capture light from many more planets. For example, Oppenheimer and his colleagues are part of Project 1640, which is looking for Jupiter-sized planets around some 200 stars. Later this year, the Gemini Planet Imager, an instrument that will be mounted on a telescope in Chile, will begin a similar task, searching about 600 stars.

Eventually, similar telescopes will image smaller, rocky worlds, says exoplanet scientist Mark Swain of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. “Ultimately, with better instruments, people will be able to use these methods on Earthlike planets.”

Back Story | DIRECT DETECTION

An early image of planets orbiting a star other than the sun, captured in 2008, depicts three of the four planets (arrows) around HR 8799. The star lies about 130 light-years away. Credit: Courtesy of C. Marois/NRC-HIA, W.M. Keck Observatory

Exoplanets are usually seen only indirectly. They can be found by observing periodic dimming of a distant star at regular intervals (a sign of an orbiting planet’s regular passage across the face of its sun) or by measuring small movements in a star caused by a planet’s gravitational pull. Direct observation is much more difficult. The brightness of the planets orbiting HR 8799 made them among the first exoplanets to be imaged. Christian Marois of the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory in Victoria, British Columbia, and colleagues spotted three of the four HR 8799 planets in 2008 using the Gemini North and Keck II telescopes on Hawaii’s Mauna Kea, and came upon the fourth two years later while observing the system with the Keck II telescope.