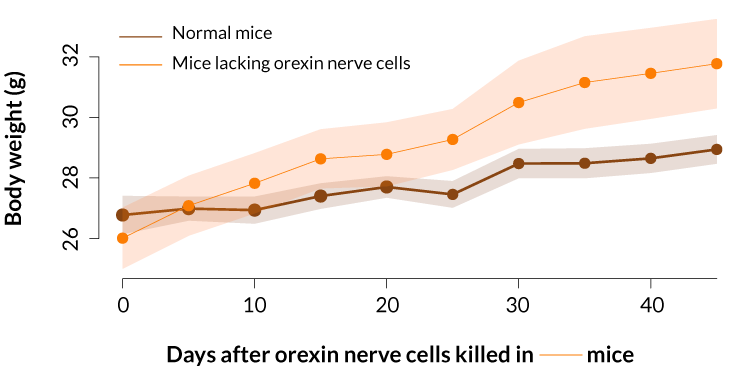

Eating shuts down nerve cells that counter obesity

Mouse study offers hints of orexin’s role in weight gain and narcolepsy

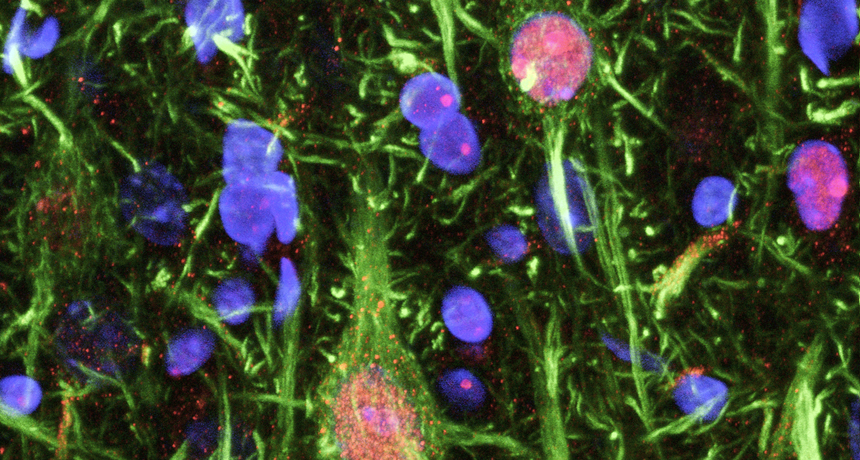

DIET AID Nerve cells that produce a molecule called orexin (also known as hypocretin, pink) may counter obesity, a study of mice suggests.

C.J. Guerin, PhD, MRC Toxicology Unit/Science Source