Evolving in Their Graves

Early burials hold clues to human origins

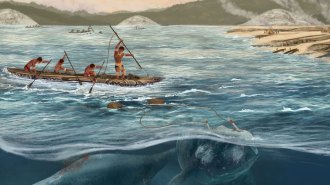

Sometime within the past 40,000 years, Neandertals disappeared from Europe, modern-looking people replaced them, and a wave of cultural change washed over the region. New techniques for fashioning tools from bone and stone came into use. Artistic expression increased markedly: Paintings appeared for the first time on cave walls, and sculpted figurines and objects of personal adornment became widespread. Other cultural practices, such as honoring the dead, either arose or grew more complex.

If an abrupt flowering of new cultural practices in Europe clearly coincided with the first appearance of modern humans, it would suggest that the newcomers represented a species that was different from Neandertals and had distinct behavioral capacities. On the other hand, evidence that cultural innovations stemmed from continual, gradual refinements of behavior would suggest that Neandertals, perhaps by interbreeding with other groups, evolved into modern people.

Whether Neandertals were evolutionary dead ends, as the first hypothesis suggests, or our ancestors is a major controversy in the study of modern human origins.

Anthropologists are digging for answers in the debate between these two ideas. Determining how and when prehistoric people began to bury their dead—and whether symbolism and ritual were involved in those first burials—could produce important insights into the development of modern humans.

But the scientists studying burials don’t agree on how to read the clues they’ve found. Some researchers see archaeological support for the idea that modern humans introduced intentional burial into Europe. If this behavior turns out to be unique to modern people, it would add weight to the two-species model.

Others, in contrast, maintain that the complexity of burial practices in Europe developed gradually from the time when Neandertals occupied the region into the era when modern humans dominated it.

Intentional burial

Many remains recovered in Europe from the Upper Paleolithic, the period from approximately 40,000 to 10,000 years ago, are widely recognized as products of intentional burial. These corpses were found mostly in caves, often alone but sometimes in groups that had been buried simultaneously or over a period as long as several millennia. Remains, sometimes along with manufactured objects and personal effects, had been put into earth mounds or burial pits in or outside the caves.

Less clear, however, is whether Neandertals or human populations buried their dead during the Middle Paleolithic, which immediately preceded the Upper Paleolithic and began 150,000 to 250,000 years ago. Even among the anthropologists who hold that there was intentional burial during the Middle Paleolithic, debate flares over whether hominids of the time attached symbolic importance to the act or it was only a rudimentary, utilitarian routine.

A handful of anthropologists, including Robert H. Gargett of the University of New England in New South Wales in Australia, contends that human fossils recovered from the Middle Paleolithic show no clear evidence of intentional burial. Gargett has hypothesized that all alleged intentional burials from the time could be explained by natural processes that could cover a body with rocks and soil.

Gargett and other anthropologists study a fossil’s archaeological context—bones’ and objects’ positions in the earth relative to each other—to determine how the remains came to be preserved and arranged as they were found. This analysis can help determine whether contemporary people had handled the corpse in some way or whether processes such as animal scavenging and weathering could explain the state of the remains.

Many excavations conducted before about 1960, however, lacked a systematic approach to recording aspects of remains’ archaeological context. Only a handful of sites has been discovered and carefully excavated since that time.

One significant aspect of a hominid fossil’s context is whether funerary objects are present. Numerous early Upper Paleolithic sites contain necklaces, bracelets, hunting weapons, and other objects fashioned from stones or animal bones and teeth. Archaeologists call such objects, when buried with a body, grave goods.

Ocher, a reddish pigment, also often appears on certain items and body parts of interred individuals in ways that indicate it was ritually applied. No Middle Paleolithic burials in Europe and only a few in Asia, however, provide evidence of ocher.

Another aspect of context frequently considered is whether the remains have been found whole, or nearly so, with bones in their correct anatomical positions. Since such a so-called articulated skeleton, common from the Upper Paleolithic, must have been protected from the elements and scavengers, the body probably received burial at the time of death.

Gargett, however, is skeptical about making that assumption at the Middle Paleolithic sites that many other researchers describe as intentional burials. Deliberate burial is not necessary to account for the preservation of articulated skeletal remains, he holds.

For example, Gargett notes, partial collapses of caves or rock overhangs could kill and bury anyone taking shelter there. Such luckless hominid victims may have had their bones broken but would otherwise be entombed in an articulated form. Any possessions with them at the time of death could later be mistaken for grave goods. This type of demise would also explain the absence of ocher in most Middle Paleolithic sites.

If Gargett is right that the apparent burials in Europe before the Upper Paleolithic are products of natural rather than ritual processes, then modern humans’ arrival at the beginning of that period would coincide with the region’s first instances of symbolic burial practices.

Iain Davidson, Gargett’s colleague at the University of New England, is emphatic: “Modern humans were—and Neandertals were not—deliberately buried.” That cultural difference reflects a cognitive sophistication in one group of people unmatched in the other, he says.

Behavior shift

Other researchers interpret existing burial evidence as closely linking the Middle and early Upper Paleolithic. The transition between the two periods doesn’t coincide with a notable shift in cultural behavior, contends Geoffrey A. Clark of Arizona State University in Tucson.

If Neandertals and modern humans share the same behavioral adaptations, they were almost certainly the same species, says Clark.

In the August-October Current Anthropology, Clark and his graduate student Julien Riel-Salvatore examine evidence of intentional burial among the remains of 77 Middle and early Upper Paleolithic hominids exhumed in Europe or western Asia during more than a century of digs.

While larger quantities of grave goods, and more complex ones, typically appear with Upper Paleolithic remains than with Middle Paleolithic corpses, Clark argues that there’s no quantum leap in behavior at the Middle-Upper Paleolithic transition.

“We aren’t justified in making a generalization about cognitive differences between Neandertals and moderns,” he says. He suggests that burial and other cultural practices arose gradually, were employed sporadically, and were probably developed independently by humans and Neandertals.

In Riel-Salvatore and Clark’s sample, the 45 graves from the Middle Paleolithic are generally less elaborate than the 32 from the Upper Paleolithic. Nearly 90 percent of graves from the later period include grave goods, and in many cases, survivors applied ocher to certain items and body parts before interring the dead.

The Middle Paleolithic graves, while less complex, give evidence of deliberate burial, the researchers contend. Moreover, there are no clear differences between the graves of 32 Neandertals and those of 13 modern humans. About half the burials of both groups contained apparent grave goods of some sort, such as bone fragments, stone tools, and rocks placed over the skeleton. Perhaps, some researchers speculate, surviving comrades thought these objects would equip the deceased for an afterlife. Two sites, both featuring physically modern people, contained hints of ocher. A third, at Shanidar, Iraq, contained remains of flowers that Neandertals may have sprinkled on the corpse of a fallen comrade.

A “mosaic” pattern of early intentional burial—that is, its off-and-on appearance during the Middle Paleolithic before it became common and more elaborate during the following period—indicates an underlying continuity in Paleolithic peoples’ capacity for culture, says Clark. “Human cognitive evolution is an emergent property, not something that comes on as a light switch 40,000 years ago,” he says.

Lawrence G. Straus, an anthropologist at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, notes, “There are differences [in behavior] between human and earlier Homo [species, including Neandertals], but not everything happened all at once.”

Straus and Clark agree that the most concentrated phase of cultural change in Europe in the Paleolithic occurred during the last glacial maximum. At that point about 18,000 years ago and well after the Middle-Upper Paleolithic transition, prolonged cold and advancing glaciers forced people to take refuge close to the Mediterranean. Innovations at that time in weapons building, cave painting, and other practices represent clear evidence of cultural change without attendant biological evolution. The researchers reason that earlier advances, such as burial, similarly required no evolutionary change among the human ancestors.

Evidence from the Near East underscores the argument that changes in burial practices were unrelated to biological evolution, says Francesco d’Errico of Bordeaux University in France. Neandertals and modern humans coexisted or alternated occupation in that region for much of the Middle Paleolithic.

Excavated remains of members of both groups don’t bear out the expectation that contemporary differences in behavior would be identifiable if the groups were separate species, says d’Errico. “Neandertals didn’t produce that much [grave goods and other evidence of intentional burial], but contemporary humans didn’t produce that much, either,” he says.

In fact, says d’Errico, there are Near Eastern sites, such as Tabun in Israel, that are as much as 160,000 years old and have stone tools associated with Neandertal remains. These provide as convincing proof of burial as anything produced by early contemporary humans.

In a commentary that accompanies Riel-Salvatore and Clark’s recent Current Anthropology paper, d’Errico maintains, “Neandertals were fully capable of symbolic behaviors and may even have produced them before contact with anatomically modern humans.”

The more elaborate assemblages of goods found in Upper Paleolithic graves, he argues, indicate the increasing complexity of human societies, not a fundamental change in the human mind.

Functional or symbolic?

An intermediate conclusion is possible. Margherita Mussi of the University La Sapienza in Rome says, “I am perfectly convinced that there is excellent evidence of [Middle Paleolithic] burials.” However, she interprets early intentional burial by Neandertals as more functional than symbolic. “Corpses must be disposed of [because] remains, human or not, can easily attract large carnivores,” Mussi says.

The increased complexity and effort involved in the more recent burials by modern humans may reflect the addition of symbolic or ritual aspects. In another commentary in Current Anthropology, she cites evidence from 23 modern-human burials in Italy during the period from 30,000 to 20,000 years ago.

More than half of these corpses lay in an extended position, which requires buriers to dig a longer grave than is needed to contain a flexed body. At least 16 of the sites contained ocher, and nearly all had grave goods in them. These characteristics are all less common or entirely absent in Neandertal burials, Mussi notes.

Similar to Gargett’s position in its implications, the hypothesis that a primarily functional behavior—the disposal of a body—developed into a symbolic ritual at the Middle-Upper Paleolithic transition favors the model of evolution in which modern humans replaced Neandertals.

Unless European soils yield more Paleolithic remains that can be excavated with modern techniques, the debate over the origins of intentional burial will be difficult to resolve. For now, at least, the truth lies as well-interred as buried bones.