Exploring the Red Planet

Mars Odyssey set to begin its mission

Last week, flight controllers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., breathed a collective sigh of relief. Although in 1999 they had lost the last two spacecraft that journeyed to Mars, their current mission to the Red Planet had completed a risky maneuver, using the friction of the Martian atmosphere to begin settling into its designated orbit 400 kilometers above the surface. Early next month, if all continues according to plan, the Mars Odyssey craft will begin a 2-year exploration of the composition of the Martian surface, hunt for near-surface deposits of water, and examine the planet’s radiation background.

Odyssey embarks on its mission at a time when questions about past and present conditions on the planet, including its water content and ability to harbor life, seem more puzzling than ever.

“We’re in state of maximal confusion,” says planetary geologist David A. Paige of the University of California, Los Angeles.

Channels or canals?

People have associated Mars with water ever since Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaperelli peered through a telescope in 1887 and saw a pattern of linear markings on the Martian surface. He called them canali, the Italian word for channels, but the word was mistakenly translated into English as canals.

The features Schiaperelli saw turned out to be artifacts of his telescope. But beginning in the 1970s, Mariner 9 and several later NASA missions returned images that revived watery notions about the Red Planet. Some pictures show sinuous networks of valleys that resemble dry riverbeds. Other images reveal features that seem to have been carved into the Martian landscape by a catastrophic outpouring of water. Those data convinced most planetary scientists that Mars was once wetter and therefore warmer than it is now. Many suspect that oceans flooded some regions and that rivers coursed through others. All of which supports the notion that life may once have flourished on the Red Planet.

If there were oceans in the distant past, the water somehow has disappeared from view. Perhaps it went underground or evaporated into space. For decades, spacecraft data had indicated that present-day Mars, with an average surface temperature of –60C and a surface pressure less than one-hundredth that of Earth, has been essentially inactive for billions of years.

Newer images and other observations made by the Mars Global Surveyor spacecraft, however, have revealed that Mars isn’t just a frozen desert. Rather, the planet is undergoing dramatic changes on both local and global scales.

Close-up images taken by Surveyor, which has orbited Mars since 1997, hint that in some of the planet’s coldest regions, water has recently rushed to the surface (SN: 7/1/00, p. 5: Martian leaks: Hints of present-day water). Newer measurements, reported last December, suggest the planet may be undergoing a climate change that could warm it significantly.

Scientists are hoping that Mars Odyssey–along with a fleet of other orbiting craft and rovers to be launched over the next 5 years–will begin to answer some of the riddles about the Red Planet. Odyssey was originally designed to have its own lander and rover, but NASA decided to scuttle that plan after the back-to-back losses of the Mars Climate Orbiter and the Mars Polar Lander in 1999.

“The primary theme is, Where is the water today and where has it been in the past?” says Jonathan I. Lunine of the University of Arizona in Tucson. “Was the water so abundant that it has been able to alter the chemistry of minerals on the surface?”

The Odyssey spacecraft comes equipped with several devices that will explore the Red Planet in new ways. A gamma-ray spectrometer will record the abundance of chemical elements in the surface, providing a global map of the composition of the Martian crust. The spectrometer also features two neutron detectors that will search for hydrogen–a proxy for water–down to a depth of 1 meter.

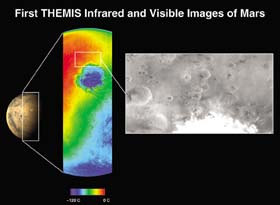

Another instrument, the thermal emission imaging system (THEMIS), is a combination camera and thermal infrared spectrometer. Using infrared detectors, it will identify the mineral content of surface rock at spatial scales one-fiftieth as fine as any previously attempted. Minerals chemically altered by the flow of water should be easily detected this way. The instrument will also make daily temperature maps of the Martian surface, providing information on the exchange of water and carbon dioxide between the planet’s atmosphere and its polar caps. The maps may spot signs of active hydrothermal systems such as heat emerging from erupting volcanoes.

A third device, the Mars Radiation Experiment (MARIE), is designed to measure radiation near the planet’s surface and begin to assess how human explorers could operate safely in the Martian environment. However, a computer glitch caused MARIE to stop transmitting data during the journey to Mars, and NASA won’t attempt to reactivate the sensor until Odyssey begins its mapping mission next month.

Surprises and paradoxes

Instruments aboard Mars Global Surveyor have revealed a host of surprises–and paradoxes–about the planet. A laser altimeter, which stopped working last August, had measured the height of mountains to an accuracy of centimeters. Bouncing a laser beam off the Martian landscape, the altimeter found evidence of valleys carved by water and huge basins that may once have held more than seven times the water in the Mediterranean Sea (SN: 12/9/00, p. 372).

On the other hand, Surveyor’s thermal emission spectrometer has found no evidence of water-altered minerals on the Martian surface. According to geologists, receding oceans on Mars would most likely have left behind an abundance of such minerals. Yet other experts believe that shifting veneers of dust would have covered such deposits over millions of years, making them difficult to identify from orbit without an extremely high-resolution camera, notes James B. Garvin, the lead scientist for Mars exploration at NASA headquarters in Washington, D.C.

Surveyor’s magnetometer has revealed a magnetic field pattern that some scientists interpret as evidence that the Red Planet has undergone tectonic activity: Chunks of the planet’s crust may have slid underneath each other, the same global process that formed Earth’s continents.

The spacecraft’s high-resolution camera, which has taken more than 100,000 snapshots of Mars, has yielded its own surprises. The camera has provided close-ups of about 1 percent of the planet, revealing details as small as 1.5 meters across. While analyzing several of these images, researchers identified hundreds of newly formed gullies, a finding that suggests that water gushed to the surface relatively recently. Curiously, the gullies reside on the sides of steep cliffs in some of Mars’ coldest places, where water should be ice, not liquid.

Although water reaching the Martian surface wouldn’t remain liquid for long, heat from the planet’s interior could melt a reservoir of ice a few hundred meters below the surface, notes geologist Michael C. Malin, who built the Surveyor camera. He and Kenneth C. Edgett, both of Malin Space Science Systems in San Diego, suggest that when the water reaches the chilly surface, it freezes and forms an ice dam that blocks liquid water still percolating beneath it.

According to their model, the pressure from the liquid eventually becomes so great that it breaks through the dam and gushes onto the surface with enough force and volume to create gullies before freezing and evaporating.

Other scientists contend that water, which may be scarce in both the atmosphere and on the surface, didn’t sculpt the gullies. Instead, they argue that carbon dioxide, the most abundant constituent of the atmosphere, did the job.

Lunine, his Arizona colleague Timothy D. Swindle, and Donald S. Musselwhite of NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, contend that carbon dioxide gas from the Martian atmosphere seeps into the pores of rocks on the steep-sided cliffs and condenses there into ice during winter. In their view, additional frozen carbon dioxide also forms on the exposed surface of the rocks, covering them like a lid.

In the spring, the carbon dioxide within the rocks warms and expands, turning to liquid as pressure builds under the lid. At the same time, the lid begins to evaporate and the underlying liquid bursts through.

But it isn’t the carbon dioxide liquid that forms the gullies, according to the model described by Lunine and his colleagues in the July 2001 Geophysical Research Letters. They argue that the carbon dioxide liquid that bursts through quickly vaporizes and cools, producing a snow suspended in a plume of carbon dioxide gas that hasn’t yet cooled enough to condense. The suspended material joins rock debris to form a slurry that flows like a liquid and carves the gullies.

Because the carbon dioxide must liquefy and burst rapidly through the lid, the model requires that the gullies occur on cliff faces that are subject to a dramatic temperature swing between winter and spring. If Surveyor or Odyssey find evidence of gullies in flatter terrain that aren’t prone to such swings, the model could be in trouble.

Although Odyssey doesn’t have the resolution to detect near-surface water under an individual gully, its broad view might still shed light on the origin of the gullies. If, for example, the data from the craft reveal that that gullies tend to lie in areas with large underground water deposits, Malin’s and Edgett’s water-based theory would gain support.

Odyssey’s search for water is indirect. Its neutron spectrometers can identify places on Mars where neutrons scattered off the surface have, on average, a lower energy than in other areas. Because collisions with hydrogen, the lightest element, most efficiently sap energy from neutrons, the energy deficit indicates the presence of hydrogen. Most hydrogen is tied up in water.

“My prediction is that we’ll see hydrogen concentrations at all kinds of scales on Mars, and we’ll all be scratching our beards trying to figure out what they mean,” says Garvin. “In some cases, it will indicate buried ground ice; in other cases, intriguing reservoirs of water-bearing or hydrogen-bearing minerals.”

Higher resolution

THEMIS may also play a role in determining the origin of the gullies. The system, which has much higher resolution than a similar instrument on Surveyor, can zoom in on individual gullies and examine the minerals in surface rock. If a recent flow of water formed the gullies, it would have left behind water-borne deposits of minerals that could display a unique infrared signature.

Even if the gullies were carved by water, these features may indicate but a tiny amount of the present-day water supply on the Red Planet, cautions Garvin of NASA headquarters. Surveyor may have spied the gullies first simply because these features are more exposed than other water-carved landforms or because the craft has yet to examine most of the planet in the same fine detail, he suggests.

Alternatively, he notes, the gullies could indicate the last places on Mars to still have reservoirs of liquid water. At other sites, the water may have disappeared long ago.

Several Mars investigators have suggested that a vast area in the northern plains of Mars could be the sediment of what once was a large body of standing water. Two years ago, researchers reported that Surveyor’s laser altimeter showed the region to be unusually flat. James Head of Brown University in Providence, R.I., and his colleagues say that the flatness strongly suggests an ocean or lake resided there hundreds of millions of years ago. Yet Surveyor’s camera found no evidence of a shoreline at the edge of the region. Garvin notes that on Earth, standing bodies of water that have evaporated leave behind a telltale “bathtub ring,” a boundary between the place where the water once was and adjacent landforms that hadn’t been underwater.

By mapping the elements and minerals in the Martian crust, Odyssey could help sort out the seemingly contradictory information from Surveyor. “Mars Odyssey is a crucial next step in understanding the history of Martian water and in locating potential sites where water has been recently,” says Lunine.

Ultimately, the search for water may require radar detectors that will fly aboard two Mars-bound craft–an Italian mission set for launch in 2003 and a NASA mission scheduled to take off in 2005. NASA has also begun developing rovers capable of climbing the steep cliffs where the gullies reside. These all-terrain robots, considerably larger and more mobile than the wagon-size rover carried by Mars Pathfinder in 1997, could look for direct evidence of recent water-related activity.

Evaporating ice caps

Observations by Odyssey and Surveyor may also illuminate a startling set of findings about the present Martian climate reported in the Dec. 7, 2001 Science. Using Surveyor’s camera, Malin and his colleagues found that during a full Martian year–about 2 Earth years–the walls of pits in the south polar ice cap receded by 1 to 3 m. The cap is mostly frozen carbon dioxide, and the dramatic shrinkage suggests that large amounts of the material have evaporated into the Martian atmosphere.

If that trend continues, the weight of the Martian atmosphere could increase by about 1 percent per decade, Malin’s team estimates. With a greater atmospheric pressure, water is more likely to remain a liquid on the surface. More to the point, in time the planet could become significantly warmer and wetter, perhaps returning to conditions that prevailed much earlier in the planet’s history.

Indeed, theorists have calculated that over hundreds of thousands of years, Mars’ axis of rotation can tilt by as much as 50 degrees. If so, very different climate conditions could have permitted a substantial amount of liquid water on the planet’s surface some time in the distant past.

The new findings also suggest that the carbon cycle might have been as active in the recent past as it has been during the past Martian year. If the activity caused an increase in the planet’s atmospheric pressure, it would make it “more likely that water was present as a liquid near the surface” in recent times, says Malin. The gullies could be visible signposts of such an occurrence, he and his colleagues note.

If the environment on Mars has changed as much and as quickly as the Surveyor images suggest, then several spacecraft and landers set to explore the Red Planet over the next few years should also be able to detect signs of the rapid changes.

Relying on Odyssey as their water scout, two spacecraft will carry the ultimate in high-tech dowsing rods. Both the Italian space agency’s Mars Express mission and NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance mission will employ radar that can hunt for water buried as deep as a kilometer beneath the surface.

The possibility of such reservoirs opens up the most tantalizing issue of all. If Mars periodically goes through freeze-and-thaw cycles, buried ice deposits “could conceivably be places that are refuges for life,” says Lunine.

“We don’t know whether that’s the case or not now, but I’m now optimistic we’ll have some answers within the next decade.”