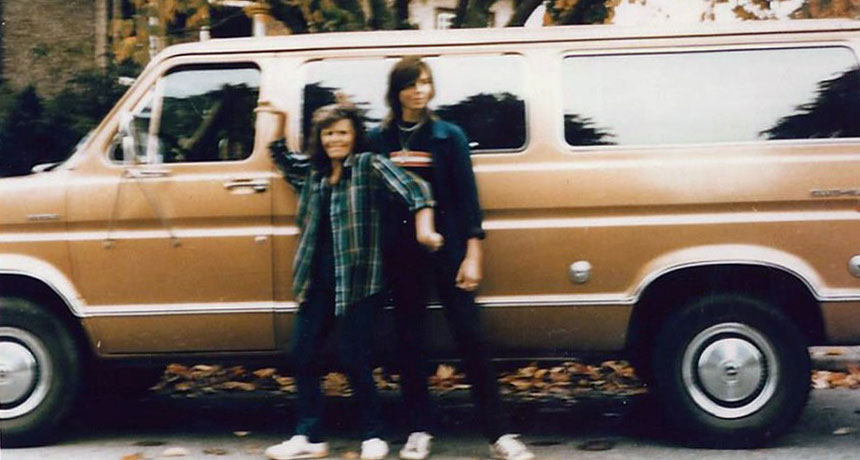

COLD CASE FIRED UP In 1987, a young Canadian couple, Tanya Van Cuylenborg, 18, (left) and Jay Cook, 20, (right) was killed while on a trip to Seattle. Police used a new, and controversial, DNA detective method to find and arrest a suspect in the case.

Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office

For the second time in less than a month, DNA probes of family trees in a public database have helped police catch a murder suspect.

On May 17, detectives in Washington arrested 55-year-old William Earl Talbott II of Seatac for the 1987 double murder of Jay Cook and Tanya Van Cuylenborg. A new DNA sleuthing technique called genetic genealogy led to Talbott’s capture. His arrest came just weeks after police in California used the new trick to identify a suspect in the Golden State Killer case (SN Online: 4/29/18).

Arrests in these two cold cases are probably just the beginning of the technique’s use.

Parabon NanoLabs, a DNA-forensics company based in Reston, Va., announced May 8 that it has already used 100 genetic profiles generated from crime-scene DNA to search the public genealogy database GEDmatch. So far, the company has identified about 20 cases in which genetic genealogy alone could pick out a likely suspect. One of those profiles led investigators to Talbott.

Another 30 of the 100 cases may be solvable with a combination of genetic genealogy and additional police work, says genetic genealogist CeCe Moore, founder of The DNA Detectives, a genetic-genealogy group with nearly 89,000 members on Facebook. The group focuses on helping adoptees and other people with unknown parents find their biological families. Moore is working with Parabon to identify possible perpetrators in murder and rape cases.

“It’s impossible not to feel the satisfaction of bringing to justice people who have evaded responsibility for pretty heinous crimes,” says New York University School of Law professor Erin Murphy.

New clues

Genetic genealogists used crime-scene DNA to probe a genealogy website called GEDmatch. Two people in the database shared some DNA with the supposed killer, both at the second-cousin level. That finding suggested that each person probably shared great-grandparents with the suspect. Reconstructing these people’s family trees led police to further investigate and arrest a suspect.

But Murphy and some other privacy experts are concerned that such cases are making innocent people the subjects of investigations just because those people happen to share DNA with a relative whom they may not even know. Digging through the family trees and DNA of people without their knowledge and consent is akin to searching without a warrant or probable cause, Murphy argues.

What’s more, police might extend the investigations to less serious crimes, she worries. “There’s no rule saying police can only do this sort of genetic sleuthing if it’s a homicide or rape.” Or, while looking through financial or other records of possible suspects from the family trees, detectives might start investigating people for another thing that they had never been under suspicion for. “That’s something we haven’t done in our country. We haven’t said police should just investigate people randomly and see what they turn up,” she says.

In both murder cases, investigators created a genetic profile of a suspect from DNA collected at a crime scene, put the genetic data into a format similar to the raw data from such consumer testing companies as 23andMe, and uploaded it to GEDmatch. (The public database allows people who do genetic testing through one company to find DNA matches with relatives who tested through a different company.)

Parabon already had a DNA profile of the Cook-Van Cuylenborg suspect handy. It had been used to generate a sketch of what the suspected killer might look like at three different ages.

That profile also contained information that could be used to create the suspect’s family tree. To build it, Parabon tested about 800,000 variable spots in the DNA, says geneticist Ellen Greytak, the company’s bioinformatics director. These spots — called single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs (pronounced “snips”) — are places in the genetic instruction book where people differ in one DNA letter. Patterns of SNPs are used to detect pieces of DNA shared by relatives.

Parabon, which was already using genealogy databases to identify Jane and John Does, had previously considered mining the data for clues about perpetrators of crime. But, Greytak says, “we weren’t sure what the public reception was going to be.” Would GEDmatch users be upset if they found out police were using their genetic information in investigations?

Since the public’s reaction to the widely publicized Golden State Killer case was generally positive, Parabon decided to move ahead with its plans, Greytak says. “We now feel that people are aware, and if they continue to participate [in GEDmatch], they’re okay with that usage.”

DNA from Van Cuylenborg’s murder scene matched two people in the GEDmatch database, both at the second-cousin level. That finding suggested that each person probably shared great-grandparents with the suspect.

Moore filled in the family trees of both people and found that one tree led to Talbott’s mother and the other to his father. Talbott, the couple’s only son, became the prime suspect. Police tailed him and got DNA from a cup he threw away, which matched the crime-scene DNA. Detectives from the Snohomish County and Skagit County Sheriff’s offices arrested Talbott and charged him with the first-degree murder of Van Cuylenborg. Police are still investigating what role he may have played in Cook’s death. Talbott has pleaded not guilty to the murder charge.