Scientists grow humanized kidneys in pig embryos

The feat is a step closer to growing organs for transplant

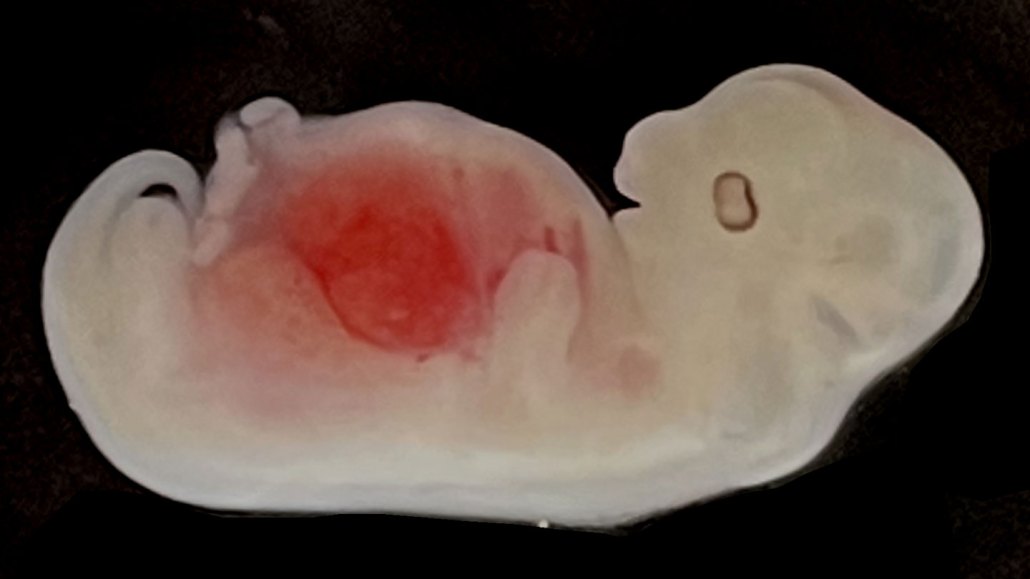

Scientists introduced human stem cells into pig embryos (one shown) engineered to lack a kidney. The stem cells then differentiated and grew into a new organ made mostly from human cells.

J. Wang et al/Cell Stem Cell 2023

Scientists have successfully grown kidneys made of mostly human cells inside pig embryos — taking researchers yet another step down the long road toward generating viable human organs for transplant.

The results, reported September 7 in Cell Stem Cell, mark the first time a solid humanized organ, one with both human and animal cells, has been grown inside another species.

“This is a considerable progress in human-animal chimerism,” says Tao Tan, a cell biologist at the Kunming University of Science and Technology in China, who helped create the first chimeric human-monkey embryo in 2021 but was not involved in the current study.

In the United States alone, more than 100,000 people currently sit on an organ transplant waiting list. A vast majority of those people need a kidney transplant. To meet this demand for life-saving organ transplants, scientists have been pursuing new methods to grow organs and tissues in animals (SN: 1/26/17).

Advances in the last few years include growing rat organs in mice (and vice versa) and humanized skeletal muscle and endothelial tissue in pigs. But significant hurdles remain, due in part to how challenging it is for human cells to thrive inside a foreign host. Human induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPSCs, which function as a sort of “starter kit” for growing many kinds of human tissue, often die when introduced into animals because the species’ cells have different physiological needs.

Stem cell biologist Liangxue Lai, of the Guangzhou Institutes of Biomedicine and Health in China, and his team spent more than five years refining their methods to enhance the human stem cells’ survivability.

While the pig embryos were still just single cells, the team used the gene-editing tool CRISPR/Cas9 to edit out two genes necessary for kidney development. That created a niche in which the human iPSCs, once injected into the space, could develop into kidney cells. The human stem cells were also tweaked to have especially active genes that dampen apoptosis, or cell death, to keep the cells alive long enough to gain a foothold and begin forming the kidney.

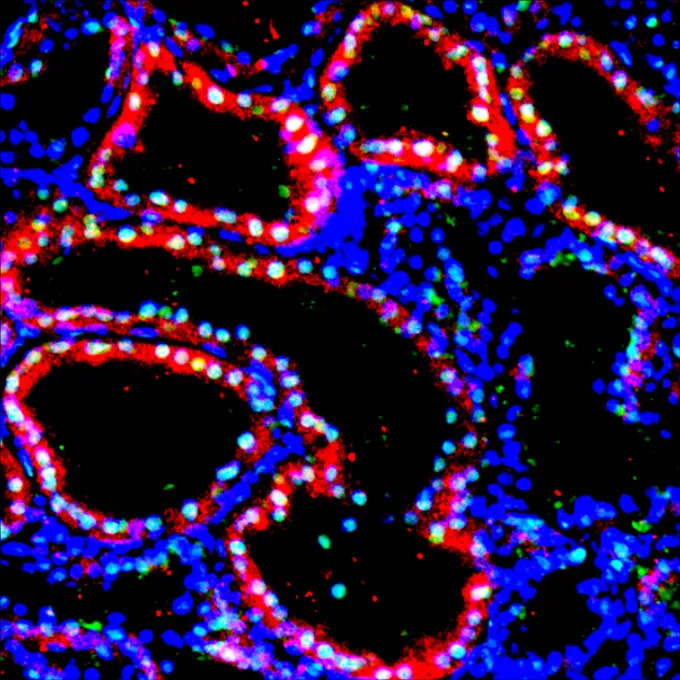

More than 1,800 embryos were then transferred into surrogate sows, of which five were harvested for study within the first 28 days. All five had normal kidneys consistent with their level of development, and the organs contained 50 percent to 60 percent human-derived cells. That’s the highest percentage of human cells yet observed in any organ grown inside a pig, Tan says. Given more time, there’s no indication that the kidneys wouldn’t continue to grow and develop normally, possibly with the human cells increasingly edging out the pig cells, the researchers say.

The study is “an important and interesting step,” says Massimo Mangiola, a transplant immunologist at New York University Langone Health who was not involved in the research. But it’s still many years out from fully functional xenotransplants, he notes.

While the stem cells did differentiate into several cell types, including kidney tubular cells and developmental tissue, the human kidney has more than 70 unique cell types that scientists will need to recapitulate. And until researchers can create an organ that is 100 percent human, it’s likely that such transplants will prompt rejection.

In addition, a few iPSCs erroneously differentiated into neural cells in the brains and spinal cords of the embryos. Mangiola says that the cells appear to be random, unlike the kidney cells, making him think they’re not likely to result in animals with human brains — which would create an ethical quandary.

To avoid such ethical issues, Lai says that moving forward the team will knock out genes that orchestrate the stem cells’ differentiation into neurons — as well as into germline cells, eggs and sperm, which pass genetic information on to offspring. The team is also pursuing growing other human organ precursors in pigs as well, including the heart and pancreas.

“We feel that we have accomplished a milestone in the field, but this is only the first step, and many challenges remain,” Lai says. “We are optimistic that with time and effort we may be able to overcome these challenges too.”