Harmless bacterium edges out intestinal germ

Clostridium scindens inhibits closely related microbe C. difficile

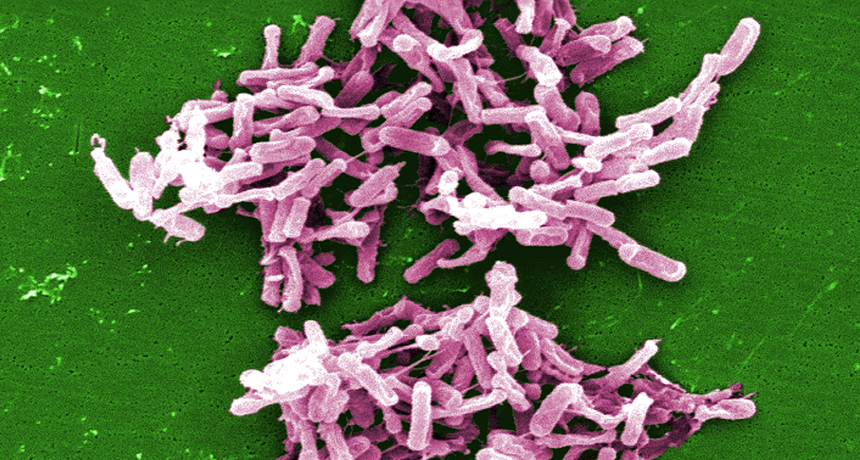

BACTERIA VS. BACTERIA Mice exposed to Clostridium difficile (shown) are protected by a related microbe, C. scindens.

Janice Haney Carr/CDC