MUMMY TUMMY Stomach tissue from a 5,300-year-old mummy known as Ötzi the Iceman revealed the presence of a virulent strain of H. pylori bacteria. Here, scientists take a sample from the mummy’s body.

© EURAC, Marion Lafogler

Ötzi the Iceman had a stomach bug.

The 5,300-year-old mummy holds DNA evidence of Helicobacter pylori, a common stomach-dwelling bacteria that can cause ulcers and other ailments, researchers report in the Jan. 8 Science.

The new work could rewrite the timeline of H. pylori evolution, and possibly even offer some insight into human migration — though not everyone is convinced.

Regardless, it’s the first time anyone has stitched together the pieces of ancient H. pylori DNA, says Daniel Falush, a statistical geneticist at Swansea University in Wales who was not involved in the study. “It’s a technical achievement,” he says. Given the age of the starting material, “I’m surprised it was possible at all.”

In 1991, scientists discovered the Iceman lodged in a waist-deep block of ice in a glacier between Austria and Italy. Over the last few decades, physical exams, body scans and analyses of Ötzi’s teeth and bones have revealed much about his life and death, including that he died from an arrow wound in the shoulder. In recent years, scientists have revealed some of Ötzi’s more intimate secrets. In 2012, Albert Zink of the European Academy of Bozen/Bolzano in Italy and colleagues reported that the Iceman was lactose intolerant, had brown hair and eyes and was infected with the bacteria that causes Lyme disease (SN: 3/24/12, p. 5).

Story continues after graphic

Mapping bacteria

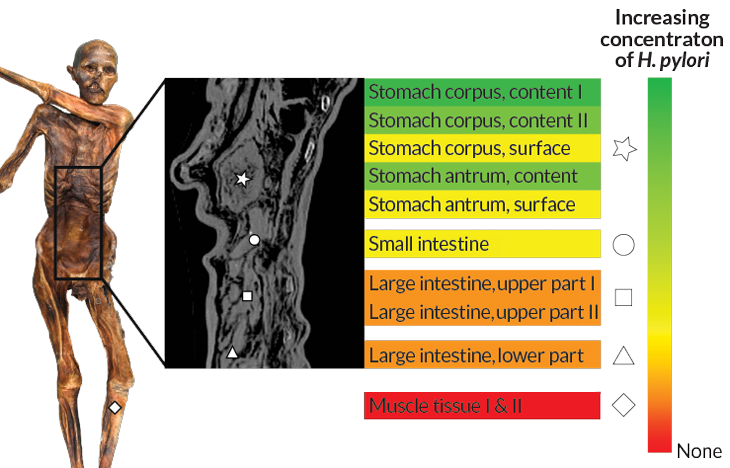

Samples taken from Ötzi’s stomach and intestines contained DNA from H. pylori, while his muscles contained no trace of the bacteria. Concentration is represented by a color gradient, starting with red (none) and increasing to green.

Zink’s team also noticed that Ötzi had a well-preserved stomach. “The idea came up: Let’s look and see if he was carrying H. pylori,” Zink says. The team defrosted the mummy, snipped out samples of his stomach and looked for microscopic signs of infection. But the inner wall of the stomach — where the bacteria typically dwell — had already crumbled away. So instead, the researchers hunted for H. pylori DNA.

They found it, mixed with DNA from other gut microbes as well as DNA from the Iceman himself. Zink’s team fished out the H. pylori bits and assembled them into a near complete copy of the ancient strain’s genetic instruction book. The researchers then compared this ancient bacterial genome with those of modern H. pylori strains.

Zink and colleagues were surprised to discover that the European Iceman didn’t have a European-looking strain. Instead, the mummy’s bacteria looked more like an Asian strain.

Today’s European strain is thought to be a mixture of ancient Asian and African strains (called AE1 and AE2). These two strains blended when humans carrying the Asian strain mingled with humans carrying the African strain. Scientists had pegged the date of this blending to sometime between 10,000 and 52,000 years ago.

But the new work suggests that the African strain didn’t make it to Europe until much later — after the Iceman’s time, some 5,000 years ago.

“Big deal,” says microbiologist Mark Achtman of the University of Warwick in England. “They’ve got one 5,000-year-old person carrying the bacteria.” To sketch out a story of human migration, the team needs to examine a lot more people, he says.

The study’s authors agree that studying more mummies would help. “We always have to keep in mind that we’re talking about one example,” Zink says.

But even one example can offer insights into ancient humans’ lives — beyond migration events. Ötzi’s H. pylori strain was a virulent one, Zink’s team discovered. Inside the Iceman’s stomach tissues, the researchers found signs of inflammation.

Says D. Scott Merrell, a microbiologist at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md.: “It suggests to me, that even as long as 5,000 years ago, people were suffering from H. pylori-associated disease.”