Lack of sleep has genetic link with type 2 diabetes

Large genomic studies show body rhythms, melatonin may influence sugar levels in the blood

Sleep is a mystery. Although no one knows exactly why, it’s required for good health. But now, scientists have found a surprisingly clear connection between sleep and a healthy body: the regulation of sugar levels in the blood. The new studies, all online December 7 in Nature Genetics, describe the first genetic link between sleep and type 2 diabetes, a disease marked by high blood sugar levels.

In the United States, the number of people with type 2 diabetes is increasing, according to a 2006 paper in the journal Circulation; while the average amount people sleep is dwindling, according to a sleep survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The investigations by three international teams of researchers suggest the trends of rising diabetes and falling sleep are linked via a protein that senses the sleep-inducing hormone melatonin. The research places bodily rhythms, including the clock that sets human sleep cycles, squarely in the blood sugar business.

This newfound link between melatonin and type 2 diabetes intrigues sleep researchers like Orfeu Buxton at HarvardMedicalSchool in Boston, who was not involved with the new work. “This is really breakthrough stuff,” he says.

The findings fill in some of the molecular details of how sleep can change blood sugar levels. The key, it appears, is a melatonin receptor, a protein on the outside of cells that senses melatonin in the blood and triggers sleep- or wake-related changes in cells.

Human bodies have a clock, an internal rhythm that dictates when to fall asleep and when to get up. Molecular timekeepers, made and degraded every 24 hours, set this daily cycle. When part of the ticking molecular clock goes awry, sleep schedules change.

Disordered sleep can spark a constellation of intertwined pathologies: Studies in humans have shown that depression, obesity, weakened immune system function and even death are all correlated with a lack of shut-eye. Population studies have shown that diabetes rates rise as sleep declines. While these data provide compelling reasons to get eight hours of quality sleep every night, they couldn’t explain how diabetes might be influenced by sleep.

The three new genomic studies show that melatonin, a major regulator of the body’s sleep clock, is closely linked to increased glucose levels and diabetes. Best known for its sleep-inducing properties, melatonin is sold as an over-the-counter, nutritional supplement to aid sleep. Melatonin levels in the body are tied to daylight: When the lights go down, melatonin levels rise and drowsiness soon follows.

The finding identifies melatonin as a “fascinating new target” for diabetes treatments, says endocrinologist Leif Groop of LundUniversity in Malmö, Sweden, and a coauthor on two of the new reports.

Two studies, one listing 109 coauthors, analyzed data from earlier studies that had measured blood sugar levels and had collected DNA samples from their participants — the larger study analyzed data from 36,610 people and the other from 2,151 people. All participants were of European descent.

In both studies, comparing the DNA sequences of participants who had high blood sugar levels with the DNA of those who had normal blood sugar levels turned up a surprise. In both studies, MTNR1B, a gene encoding a melatonin receptor, caught researchers’ attention. People with high blood sugar levels, and thus diabetes, were much more likely to have a change in a single DNA base, or letter, within the gene than were those with healthy blood sugar levels.

“The finding that the melatonin receptor has an influence on diabetes was unexpected,” Groop says.

A third paper, which analyzed results from two large studies of over 18,000 participants, took the findings a step further. The researchers showed that the same DNA change in MTNR1B identified in the other two studies — a seemingly innocuous G instead of the more common C — was correlated with high blood sugar levels, low insulin levels and most important, a greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes during the multiyear studies.

The scientists, including Groop, also did experiments that looked at how melatonin might directly interact with insulin-producing cells.

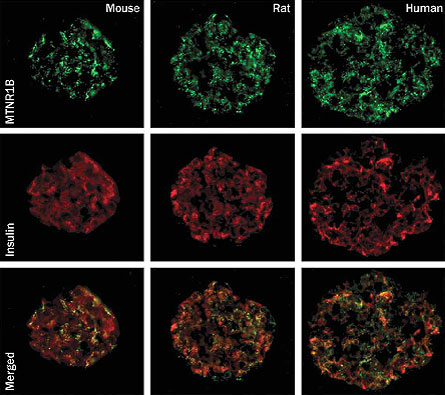

The melatonin receptor was thought to be primarily expressed in the brain — where the body’s master clock resides. Groop and colleagues now show that insulin-producing cells, called beta-cells, in the pancreas of mice, rats and humans, also have the melatonin receptor.

The presence of the melatonin receptor on the insulin-secreting cells makes it more likely that the receptor is directly controlling the output of insulin. When scientists added melatonin to human beta-cells in the lab, insulin production went down. That melatonin and insulin are connected makes sense, because in the dead of night, when melatonin levels are high, the need for insulin should be low. Researchers don’t yet know how melatonin levels are different in sleep-deprived people, and how this difference could lead to decreased insulin production.

The tie between sleep and blood sugar didn’t come as a surprise to some sleep researchers. Buxton says that evidence has accumulated for years on the relationship between sleep and blood sugar levels. “However, such a direct role for melatonin was very surprising,” he says

Researcher James Gangwisch of Columbia University in New York City says the identification of the melatonin receptor as an important regulator of blood sugar “fits well” with earlier studies looking at the effects of poor sleep on blood sugar levels.

A 2007 study found that people who get less than five hours of sleep a night were significantly more likely to have type 2 diabetes. Experiments on sleep in the lab confirm this trend: Healthy young adults who were prevented from entering deep sleep for just three nights couldn’t properly regulate blood sugar levels, a 2008 study shows. What’s more, the subjects became more resistant to insulin during the study, eventually reaching the levels of insulin sensitivity that resemble the insulin resistance of diabetic people.

Sleep-deprived subjects, Gangwisch says, crave starchy, sweet foods and don’t regulate blood sugar well. “We know it’s true, but the question is why.”

“This paper ties those two things together,” says Gonçalo Abecasis of the University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor, coauthor of one of the studies. “Sleep disrupts the circadian clock, and the melatonin receptor disrupts the circadian clock. These are two different ways to interrupt the clock, but both lead to the same endpoint of diabetes.”

“These findings raise more exciting questions than they answer,” says Buxton. But he cautions that the data on melatonin’s impact on insulin-producing cells in humans is still early. Many more studies are needed before scientists will fully understand how melatonin affects blood sugar levels and type 2 diabetes.

Groop agrees, and points to the need for more basic studies on the melatonin receptor and clinical tests of glucose levels in people who have been given melatonin supplements.

People taking melatonin to aid sleep may be just such a group. Says Abecasis, “I think it would be interesting to track incidences of diabetes in such people.”