Scientists used a special hot-water drill to carve this hole through a kilometer of ice to reach the buried Lake Mercer in West Antarctica.

Billy Collins

How microbes survive in lakes far beneath Antarctica’s ice sheet has been a mystery. Now scientists have figured out what’s on the menu for microbes in one buried lake in West Antarctica.

The lake’s bacteria and other microbial inhabitants get by on carbon that seawater left behind thousands of years ago, researchers report in the April AGU Advances. The find adds to existing evidence that, during a period of warming about 6,000 years ago, the ice sheet in West Antarctica was smaller than it is today. That allowed seawater to deposit nutrients in what is now a lake bed buried under hundreds of meters of ice.

This study is among the first to provide evidence from beneath the ice that the ice sheet was smaller in the not-so-distant past, geologically speaking, before growing back to its modern size, says Greg Balco, a geochemist at the Berkeley Geochronology Center in California.

Understanding how the ice sheet changed during past periods of warming is crucial to predicting Antarctica’s future as the world continues to warm due to human-caused climate change, says Balco, who was not involved in the new study.

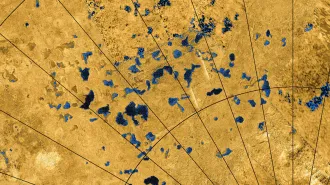

Hundreds of lakes pool under Antarctica’s massive ice sheet, the result of the underside of the ice ever-so-slowly melting due to heat from the Earth’s interior. The lakes tend to be pitch-black, near freezing and are almost all isolated from the outside world.

These less-than-ideal conditions should make them hostile to life. “If I were a microbe, I wouldn’t want to live in the cold, dark depths where I haven’t seen the sun or a new nutrient in thousands of years,” says Ryan Venturelli, a paleoglaciologist at the Colorado School of Mines in Golden. Yet billions of microbes — and even some animals — have found a way to thrive in these subglacial waterbodies (SN: 4/21/23).

As the last glacial period came to a close, starting around 15,000 years ago, ice sheets around the world retreated. Computer simulations have predicted that as the climate warmed, the ice sheet in West Antarctica may have shrunk to an even smaller size than it is today. But working out what a smaller ice sheet might have looked like isn’t easy since most of the evidence for it is now locked under ice, Balco says.

In 2018, Venturelli joined a team of about 30 scientists headed to a remote corner of West Antarctica to drill for the past. The journey took them to Lake Mercer: a body of subglacial water that today sits 150 kilometers from the sea.

It took the expedition over a week of using a hot-water drill 24 hours a day to pierce through just over a kilometer of ice to reach the lake. “There was a lot of cheering and high-fiving” when the drill finally made it through, Venturelli recalls. Lake Mercer is only the second subglacial lake in the world that scientists have ever managed to reach.

The team collected and analyzed lake water and sediment samples from the lake bed. This work revealed traces of 6,000-year-old carbon-14, a form of the element that’s made in the atmosphere and then falls to Earth. For that carbon to get past the ice, the lake would have had to have contact with the outside world.

The researchers didn’t spot any telltale signs of ancient photosynthesizing plankton, suggesting that the area wasn’t open ocean when the carbon settled in the sediment. Instead, seawater carrying the carbon must have come to the lake. That means that ocean water had to have flowed under the ice about 250 kilometers farther inland than it does today, the researchers say.

“There’s no other way to get carbon-14 in there,” Balco says. “You can’t push it through ice. Organisms can’t tunnel through. The only way for it to get it there is for ocean water to get under the ice sheet.”

Seawater does flow under the ice today — but not as far inland as the lake’s location. So the edge of the ice shelf was probably closer to Lake Mercer several thousand years ago. That suggests, the team says, that the ice sheet over West Antarctica was probably smaller back then.

Microorganisms living in this area 6,000 years ago would have feasted on the inflow from the ocean. And their descendants still seem to as well. The researchers found traces of carbon-14 in the water samples as well as in the sediment, suggesting the microbes are recycling the ancient carbon deposited in the lake bed as food.

The new study emphasizes how much information is waiting to be found in Antarctica’s hidden lakes, Venturelli says. “There are about 675 lakes under the ice sheet, and we’ve only sampled two,” she says. “I would very much like to drill into every single one of them.”