Lidar maps vast network of Cambodia’s hidden cities

Extent of Khmer Empire rising from the jungle is stunning

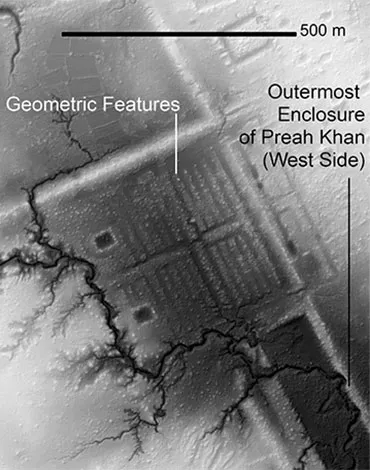

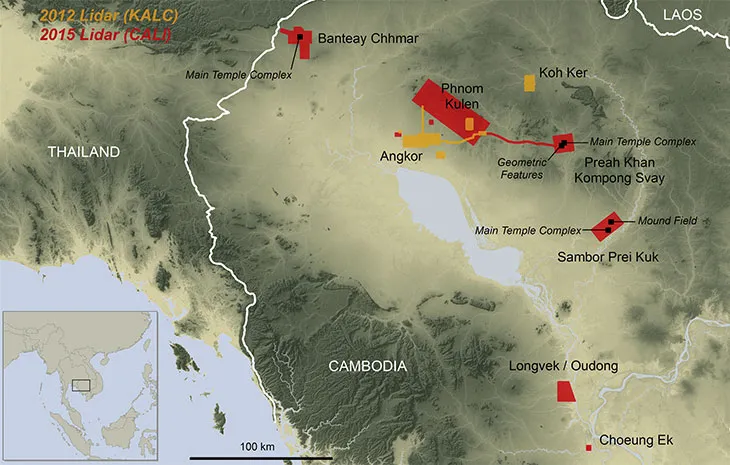

REDISCOVERED CITIES A collapsed building is located near a central temple in the 12th century city of Preah Khan in Cambodia. Aerial laser surveys of these now-forested parts of northern Cambodia have revealed the extent and layout of ancient, once-interconnected cities of the Khmer Empire.

M. Hendrickson