Linking obesity with leukemia relapses

Fat may offer sanctuary for cancerous cells, a study in mice shows

In leukemia patients, excess fatty tissue allows cancerous cells to avoid destruction by chemotherapy drugs, a study in mice suggests.

The findings, combined with tests on human leukemia cell lines, may explain why previous studies have shown that obese children and adults with leukemia are more apt to relapse than their leaner counterparts, scientists report in the Oct. 1 Cancer Research.

Other research has hinted that obesity may play a role in other cancers as well, says Steven Mittelman, an endocrinologist at the University of Southern California and Childrens Hospital Los Angeles.

Too much fat may offer a safe haven for leukemia cells during chemotherapy, says David Hockenbery, a physician at the University of Washington and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle. “This study provides striking experimental support for the clinical observation that obesity is associated with a poor prognosis in multiple cancers.”

To sort out the biological mechanisms underlying the observed link between leukemia recurrence and obesity, Mittelman and his colleagues studied obese and normal-weight mice that had been injected with cells similar to the aberrant white blood cells that cause acute lymphoblastic leukemia, or ALL, the most common childhood blood cancer. Both groups of animals were treated with a chemotherapy drug, with heavier mice getting proportionately larger doses of the drugs. Fewer of the normal-weight mice developed full-blown leukemia and substantially more of them survived.

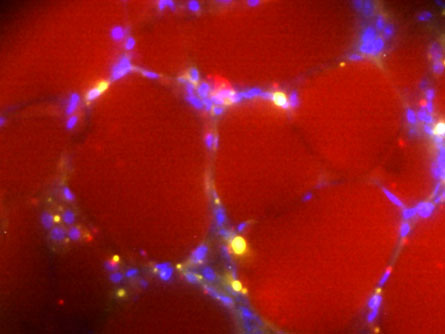

Next, the scientists cultured human ALL cell lines in lab dishes with either fat cells or fibroblasts. Fibroblasts make collagen and other connective tissues in the body and served as a control in this experiment. Cancerous cells in both groups were exposed to chemotherapy, and the malignant cells in the fatty milieu were substantially more likely to withstand the drugs than the others.

The fat cells apparently provided a “microenvironment” that supported cancer growth by thwarting the effects of chemotherapy, Mittelman says. Fat cells may act as sponges “to sop up some of the chemo,” he says.

But the effect may be more than physical. Cells send signals to one another, and fat cells might send a signal that prevents some cancerous cells from self-destructing, he says. Chemotherapy drugs typically target fast-dividing cells. Once a cancerous cell is damaged, it puts out an autodestruct signal and normally undergoes programmed cell death, called apoptosis. But in leukemia cells adjacent to fat cells in a lab dish, the autodestruct mechanism became disrupted and fewer cancerous cells died, Mittelman says.

When the researchers investigated genes involved in the autodestruct mechanism, they found that two genes known to block such cell death were switched on in cancerous cells surrounded by fat cells. Whether these two genes are the key to obese patients’ relapse risk remains to be established.

Cancerous cells “have a close relationship with the cells around them and even recruit these cells to help them survive or proliferate,” Mittelman says. “There’s two-way communication. This microenvironment has a lot to say about how cancer cells manage in the body.”