Ancient rumbles in the jungle might have left a lasting mark on the human hand.

The hand’s proportions are such that clenching the fingers creates an effective bludgeon, a pair of researchers observes. Perhaps, they propose online December 19 in the Journal of Experimental Biology, evolution played a role in making the hand such a punishing weapon.

But other scientists are skeptical. “There’s no compelling evidence that the hand evolved in this way,” says Mary Marzke, a physical anthropologist at Arizona State University in Tempe. It’s more likely that the ability to throw a good punch was just a lucky (or unlucky) consequence of evolving nimble hands suited to making and using tools.

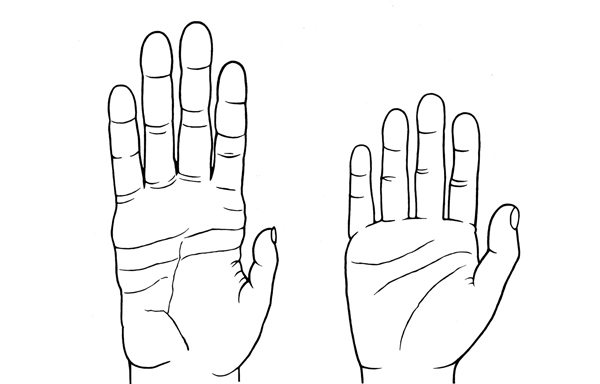

Humans have shorter fingers, a shorter palm and a longer, stronger thumb than other apes. These features give the human hand unparalleled dexterity, and most anthropologists agree these characteristics evolved as early human ancestors began making stone tools.

David Carrier, a comparative biomechanist at the University of Utah, says aggression also shaped the hand. In many early hominid species, males seem to have been much bigger than females. In living primates, such disparity in body size is often associated with a lot of fighting among males. While most male apes bite, tear or scratch their opponents, Carrier suggests that early hominids might have switched to fistfights as they spent more time on the ground and their hands became freer from climbing.

Although toolmaking undoubtedly influenced hand evolution, Carrier notes that there are many ways in which an agile hand could have evolved. The fingers could have stayed long while the thumb got bigger, or while only the palm changed. But only one hand configuration allows the formation of a fist. “We’re saying it’s obvious the hand has evolved for manual dexterity,” he says. “But a clenched fist does a better job of explaining the [exact hand] proportions we have.”

To investigate the idea, Carrier and University of Utah medical student Michael Morgan recruited 12 men with experience in boxing or martial arts for several trials that examined the strength and stability of clenched fists. When hitting a punching bag from various angles, an open-palm slap and a fist punch — with the fingers curled into the top of the palm and the thumb wrapped in front of the folded fingers — exert a similar force. But because a fist has about one-third the surface area of an open hand, a punch probably does greater damage since the force is concentrated over a smaller region, Carrier and Morgan suggest. A clenched fist also keeps the joints between the fingers and palm four times as stable as a hand simply folded in half, suggesting a buttressed fist helps protect fingers from bending and breaking during a fight.

“More work needs to be done to make this a compelling argument,” says Erin Marie Williams, a functional anatomist at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. Future studies should actually measure how much force per unit area is delivered by punches and slaps. The entire hand is probably not making contact with a victim during a slap, so the stress of such a strike may be greater than Carrier and Morgan suspect, she says.

The researchers also need to consider how an ape actually hits, Williams says. The team assumes an open-hand slap is the ancestral condition, but other forms of striking may better resemble what apes do. And other ways of hitting — like with the base of the palm — might be just as powerful and stable as a fist punch, Marzke adds.

It’s also not clear how early hominids would have fared in a boxing match. For example, the more than 3-million-year-old Australopithecus afarensis — who has not been definitively linked to using stone tools (SN: 12/18/10, p. 8) — still had a primitive hand in some ways. Whether the species’ curved fingers, for example, would have allowed individuals to form a strong fist is an open question, says Randall Susman, a functional morphologist at Stony Brook University in New York. Susman doesn’t understand why, once tools became vital, a hominid would have endangered his livelihood in a fistfight. “The last thing you want to do is expose your hand and get your fingers bitten off,” he says. “You’ll lose your toolmaking capacity.”

Another way to examine the fistfighting hypothesis, he says, is to look for evidence of punching-related fractures in the fossil record. It’s hard to find large samples of hand bones, but there might be enough Neandertal hand fossils to see whether these hominids beat each other up with their fists.