How to keep humans from ruining the search for life on Mars

Microbes from Earth might complicate human junkets to the Red Planet

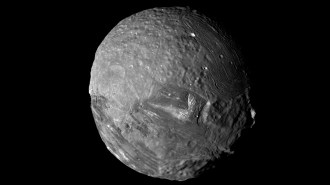

MUCKING UP MARS Scientists are racing to figure out how to keep astronauts and potential life on Mars safe from one another before humans arrive at the Red Planet.

SpaceX/Flickr

T he Okarian rover was in trouble. The yellow Humvee was making slow progress across a frigid, otherworldly landscape when planetary scientist Pascal Lee felt the rover tilt backward. Out the windshield, Lee, director of NASA’s Haughton Mars Project, saw only sky. The rear treads had broken through a crack in the sea ice and were sinking into the cold water.

True, there are signs of water on Mars, but not that much. Lee and his crew were driving the Okarian (named for the yellow Martians in Edgar Rice Burroughs’ novel The Warlord of Mars) across the Canadian Arctic to a research station in Haughton Crater that served in this dress rehearsal as a future Mars post. On a 496-kilometer road trip along the Northwest Passage, crew members pretended they were explorers on a long haul across the Red Planet to test what to expect if and when humans go to Mars.

What they learned in that April 2009 ride may become relevant sooner rather than later. NASA has declared its intention to send humans to Mars in the 2030s (SN Online: 5/24/16). The private sector plans to get there even earlier: In September, Elon Musk announced his aim to launch the first crewed SpaceX mission to Mars as soon as 2024.

“That’s not a typo,” Musk said in Australia at an International Astronautical Congress meeting. “Although it is aspirational.”

Musk’s six-year timeline has some astrobiologists in a panic. If humans arrive too soon, these researchers fear, any chance of finding evidence of life — past or present — on Mars may be ruined.

“It’s really urgent,” says astrobiologist Alberto Fairén of the Center for Astrobiology in Madrid and Cornell University. Humans take whole communities of microorganisms with them everywhere, spreading those bugs indiscriminately.

Planetary geologist Matthew Golombek of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., agrees, adding, “If you want to know if life exists there now, you kind of have to approach that question before you send people.”

A long-simmering debate over how rigorously to protect other planets from Earth life, and how best to protect life on Earth from other planets, is coming to a boil. The prospect of humans arriving on Mars has triggered a flurry of meetings and a spike in research into what “planetary protection” really means.

One of the big questions is whether Mars has regions that might be suitable for life and so deserve special protection. Another is how big a threat Earth microbes might be to potential Martian life (recent studies hint less of a threat than expected). Still, the specter of human biomes mucking up the Red Planet before a life-hunting mission can even launch has raised bitter divisions within the Mars research community.

Mind the gaps

Before any robotic Mars mission launches, the spacecraft are scrubbed, scoured and sometimes scorched to remove Earth microbes. That’s so if scientists discover a sign of life on Mars, they’ll know the life did not just hitchhike from Cape Canaveral. The effort is also intended to prevent the introduction of harmful Earth life that could kill off any Martians, similar to how invasive species edge native organisms out of Earth’s habitats.

“If we send Earth organisms to a place where they can grow and thrive, then we might come back and find nothing but Earth organisms, even though there were Mars organisms there before,” says astrobiologist John Rummel of the SETI Institute in Mountain View, Calif. “That’s bad for science; it’s bad for the Martians. We’d be real sad about that.”

To avoid that scenario, spacefaring organizations have historically agreed to keep spacecraft clean. Governments and private companies alike abide by Article IX of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which calls for planetary exploration to avoid contaminating both the visited environment and Earth. In the simplest terms: Don’t litter, and wipe your feet before coming back into the house.

But this guiding principle doesn’t tell engineers how to avoid contamination. So the international Committee on Space Research (called COSPAR) has debated and refined the details of a planetary protection policy that meets the treaty’s requirement ever since. The most recent version dates from 2015 and has a page of guidelines for human missions.

In the last few years, the international space community has started to add a quantitative component to the rules for humans — specifying how thoroughly to clean spacecraft before launch, for instance, or how many microbes are allowed to escape from human quarters.

“It was clear to everybody that we need more refined technical requirements, not just guidelines,” says Gerhard Kminek, planetary protection officer for the European Space Agency and chair of COSPAR’s planetary protection panel, which sets the standards. And right now, he says, “we don’t know enough to do a good job.”

In March 2015, more than 100 astronomers, biologists and engineers met at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., and listed 25 “knowledge gaps” that need more research before quantitative rules can be written.

The gaps cover three categories: monitoring astronauts’ microbes, minimizing contamination and understanding how matter naturally travels around Mars. Rather than prevent contamination — probably impossible — the goal is to assess the risks and decide what risks are acceptable. COSPAR prioritized the gaps in October 2016 and will meet again in Houston in February to decide what specific experiments should be done.

Stick the landing

The steps required for any future Mars mission will depend on the landing spot. COSPAR currently says that robotic missions are allowed to visit “special regions” on Mars, defined as places where terrestrial organisms are likely to replicate, only if robots are cleaned before launch to 0.03 bacterial spores per square meter of spacecraft. In contrast, a robot going to a nonspecial region is allowed to bring 300 spores per square meter. These “spores,” or endospores, are dormant bacterial cells that can survive environmental stresses that would normally kill the organism.

To date, any special regions are hypothetical, because none have been conclusively identified on Mars. But if a spacecraft finds that its location unexpectedly meets the special criteria, its mission might have to change on the spot.

The Viking landers, which in 1976 brought the first and only experiments to look for living creatures on Mars, were baked in an oven for hours before launch to clean the craft to special region standards.

“If you’re as clean as Viking, you can go anywhere on Mars,” says NASA planetary protection officer Catharine Conley. But no mission since, from the Pathfinder mission in the 1990s to the current Curiosity rover to the upcoming Mars 2020 and ExoMars rovers, has been cleared to access potentially special regions. That’s partly because of cost. A 2006 study by engineer Sarah Gavit of the Jet Propulsion Lab found that sterilizing a rover like Spirit or Opportunity (both launched in 2003) to Viking levels would cost up to 14 percent more than sterilizing it to a lower level. NASA has also backed away from looking for life after Viking’s search for Martian microbes came back inconclusive. The agency shifted focus to seeking signs of past habitability.

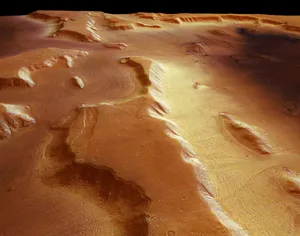

Although no place on Mars currently meets the special region criteria, some areas have conditions close enough to be treated with caution. In 2015, geologist Colin Dundas of the U.S. Geological Survey in Flagstaff, Ariz., and colleagues discovered what looked like streaks of salty water that appeared and disappeared in Gale Crater, where Curiosity is roving. Although those streaks were not declared special regions, the Curiosity team steered the rover clear of the area.

But evidence of flowing water on Mars bit the dust. In November, Dundas and colleagues reported in Nature Geoscience that the streaks are more likely to be tiny avalanches of sand. The reversal highlights how difficult it is to tell if a region on Mars is special or not.

However, on January 12 in Science, Dundas and colleagues reported finding eight slopes where layers of water ice were exposed at shallow depths (SN Online: 1/11/18). Those very steep spots would not be good landing sites for humans or rovers, but they suggest that nearby regions might have accessible ice within a meter or two of the surface.

If warm and wet conditions exist, that’s exactly where humans would want to go. Golombek has helped choose every Mars landing site since Pathfinder and has advised SpaceX on where to land its Red Dragon spacecraft, originally planned to bring the first crewed SpaceX mission to Mars. (Since then, SpaceX has announced it will use its BFR spacecraft instead, which might require shifts in landing sites.) The best landing sites for humans have access to water and are as close to the equator as possible, Golombek says. Low latitudes mean warmth, more solar power and a chance to use the planet’s rotation to help launch a rocket back to Earth.

That narrows the options. NASA’s first workshop on human landing sites, held in Houston in October 2015, identified more than 40 “exploration zones” within 50 degrees latitude of the equator, where astronauts could do science and potentially access raw materials for building and life support, including water.

Golombek helped SpaceX whittle its list to a handful of sites, including Arcadia Planitia and Deuteronilus Mensae, which show signs of having pure water ice buried beneath a thin layer of soil.

What makes these regions appealing for humans also makes them more likely to be good places for microbes to grow, putting a crimp in hopes for boots on the ground. But there are ways around the apparent barriers, Conley says. In particular, humans could land a safe distance from special regions and send clean robots to do the dirty work.

That suggestion raises a big question: How far is far enough? To figure out a safe distance, scientists need to know how well Earth microbes would survive on Mars in the first place, and how far those organisms would spread from a human habitat.

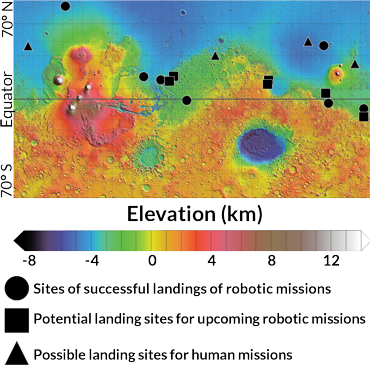

Where to?

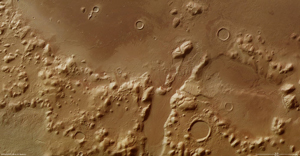

The most desirable places on Mars for human visits offer access to water in some form and are near the equator (for increased solar power and to get a boost when launching a return rocket). Rovers and landers have found evidence of a watery Martian past. Planners of future robotic and human missions have potential landing spots in mind. Map excludes polar regions.

Possible human landing sites (triangles, left to right)

This hardened dune, a potential spot for human landing, may have up to 80 meters of water ice buried beneath a few centimeters of soil.

This potential human landing site may have preserved compacted snow that fell when Mars had a different orbital tilt.

The large impact basin where the Viking 2 lander touched down on September 3, 1976, is a possible landing site for humans. Gullies (shown) on crater walls may have been formed by water.

This mountain range is thought to host ice beneath a thin layer of soil, making it a potential target for a human landing.

A no-grow zone

Initial results suggest that Mars does a good job of sterilizing itself. “I’ve been trying to grow Earth bacteria in Mars conditions for 15 years, and it’s actually really hard to do,” says astrobiologist Andrew Schuerger of the University of Florida in Gainesville. “I think that risk is much lower than the scientific community might think.”

In 2013 in Astrobiology, Schuerger and colleagues published a list of more than a dozen factors that microbes on Mars would have to overcome, including a lot of ultraviolet radiation from the sun; extreme dryness, low pressure and freezing temperatures; and high levels of salts, oxidants and heavy metals in Martian soils.

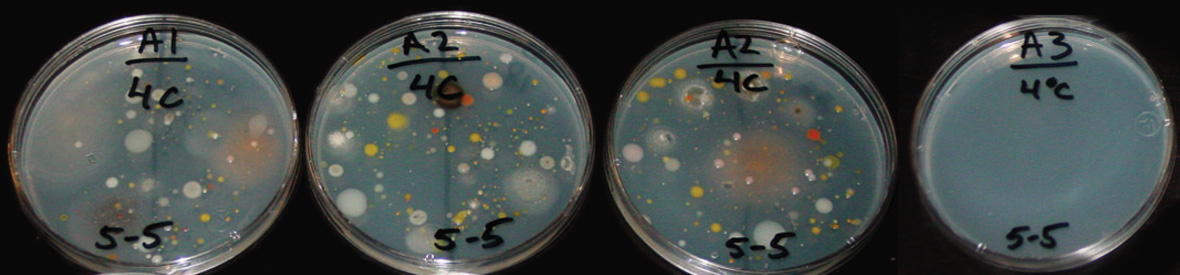

Schuerger has tried to grow hundreds of species of bacteria and fungi in the cold, low-pressure and low-oxygen conditions found on Mars. Some species came from natural soils in the dry Arctic and other desert environments, and others were recovered from clean rooms where spacecraft were assembled.

Of all those attempts, he has had success with 31 bacteria and no fungi. Seeing how difficult it is to coax these hardy microbes to thrive gives him confidence to say: “The surface conditions on Mars are so harsh that it’s very unlikely that terrestrial bacteria and fungi will be able to establish a niche.”

There’s one factor Schuerger does worry about, though: salts, which can lower the freezing temperature of water. In a 2017 paper in Icarus, Schuerger and colleagues tested the survival of Bacillus subtilis, a well-studied bacterium found in human gastrointestinal tracts, in simulated Martian soils with various levels of saltiness.

B. subtilis can form a tough spore when stressed, which could keep it safe in extreme environments. Schuerger showed that dormant B. subtilis spores were mostly unaffected for up to 28 days in six different soils. But another bacterium that does not form spores was killed off. That finding suggests that spore-forming microbes — including ones that humans carry with them — could survive in soils moistened by briny waters.

The Okarian’s trek across the Arctic offers a ray of hope: Spores might not make it very far from human habitats. At three stops during the journey across the Arctic, Pascal Lee, of the SETI Institute, collected samples from the pristine snow ahead and dirtier snow behind the vehicle, as well as from the rover’s interior. Later, Lee sent the samples to Schuerger’s lab.

The researchers asked, if humans drive over a microbe-free pristine environment, would they contaminate it? “The answer was no,” Schuerger says.

And that was in an Earth environment with only one or two of Schuerger’s biocidal factors (low temperatures and slightly higher UV radiation than elsewhere on Earth) and with a rover crawling with human-associated microbes. The Okarian hosted 69 distinct bacteria and 16 fungi, Schuerger and Lee reported in 2015 in Astrobiology.

But when crew members ventured outside the rover, they barely left a mark. The duo found one fungus and one bacterium on both the rover and two snow sites, one downwind and one ahead of the direction of travel. Other than that, nothing, even though crew members made no effort to contain their microbes — they breathed and ate openly.

“We didn’t see dispersal when conditions were much more conducive to dispersal” than they will be on Mars, Schuerger says.

The International Space Station may be an even better place to study what happens when inhabited space vessels leak microbes. Michelle Rucker, an engineer at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, and her colleagues are testing a tool for astronauts to swab the outside of their spacesuits and the space station, and collect whatever microbes are already there.

“At this point, no one has defined what the allowable levels of human contamination are,” Rucker says. “We don’t know if we’d meet them, but more importantly, we’ve never checked our human systems to see where we’re at.”

Rucker and colleagues have had astronauts test the swab kit as part of their training on Earth. The researchers plan to present the first results from those tests in March in Big Sky, Mont., at the IEEE Aerospace Conference. If the team gets the tool flight-certified to test it on the ISS, the results could fill a knowledge gap about how much spaceships carrying humans will leak and vent microbes.

A Russian experiment on the ISS may be giving the first clues. In November 2017, Russian cosmonauts told TASS news service that they had found living bacteria on the outside of the ISS. Some of those microbes, swabbed near vents during spacewalks, were not found on the spacecraft’s exterior when it launched.

Blowing in the wind

These results are important, says Conley, but they don’t give enough information alone to write quantitative contamination rules.

That’s partly because of another knowledge gap: how dust and wind move around on Mars. If Martian dust storms carry microbes far enough, the invaders could contaminate potential special regions even if humans land a safe distance away.

To find out, COSPAR’s Kminek suggests sending a fleet of Mars landers to act as meteorological stations at several fixed locations. The landers could measure atmospheric conditions and dust properties over a long time. Such landers would be relatively inexpensive to build, he says, and could launch in advance of humans.

But these weather stations would have to get in line. There’s a launch window between Earth and Mars every two years, and the next few are already booked. Weather stations would have to be stationary, so they couldn’t be added to rover missions like ExoMars or Mars 2020.

That means it’s possible that SpaceX or another company will try to send humans to Mars before the reconnaissance missions necessary to write rules for planetary protection are even built. If COSPAR is the tortoise in this race, SpaceX is the hare, along with a few other private companies. Only SpaceX has a stated timeline. Other contenders, including Washington-based Blue Origin, founded by Amazon executive Jeff Bezos, and United Launch Alliance, based in Colorado, are developing rockets that some analysts say could be part of a mission to the moon or Mars.

Now or never

Those looming launches prompted Fairén and colleagues to make a controversial proposal. In an article in the October 2017 Astrobiology, provocatively titled “Searching for life on Mars before it is too late,” the team suggested sending existing or planned rovers, even those not at the height of cleanliness, to look directly for signs of Martian life.

Given the harsh Martian conditions, rovers are unlikely to contaminate regions that might turn out to be special on a closer look, the group argues. The invasive species argument is misleading, they say: Don’t compare a microbe transfer to taking Asian parrots to the Amazon rainforest, where they could thrive and edge out local parrots. It would be closer to taking them to Antarctica to freeze to death.

Even if Earth microbes did replicate on Mars, the researchers wrote, technology is advanced enough that scientists would be able to distinguish hitchhikers from Earth from true Mars life (SN: 4/30/16, p. 28).

In a sharp rebuttal, published in the same issue of Astrobiology, Rummel and Conley disagreed. “Why would you want to go there with a dirty spacecraft?” says Rummel, who was NASA’s planetary protection officer before Conley. “To spend a billion dollars to go find life from Florida on Mars is both irresponsible and completely scientifically indefensible.”

There’s also concern for the health and safety of future astronauts. Conley says she mentioned the idea that scientists shouldn’t worry about getting sick if they encounter Earth organisms on Mars to a November meeting of epidemiologists who study the risks of Earth-based pandemics.

“The room burst out laughing,” she says. “This is a room full of medical doctors who deal with Ebola. The idea that we know about Earth organisms, and therefore they can’t hurt us, was literally laughable to them.”

Fairén has already drafted a response for a future issue of Astrobiology: “We acknowledge [that Rummel and Conley’s points] are informed and literate. Unfortunately, they are also unconvincing.”

The issue might come to a head in July in Pasadena, Calif., at the next meeting of COSPAR’s Scientific Assembly. Fairén and colleagues plan to push for more relaxed cleanliness rules.

That’s not likely to happen anytime soon. But with no concrete rules in place for humans, would a human mission even be allowed off the ground, whether NASA or SpaceX was at the helm? Currently, private U.S. companies must apply to the Federal Aviation Administration for a launch license, and for travel to another planet, that agency would probably ask NASA to weigh in.

It’s hard to know if anyone will actually be ready to send humans to Mars in the next decade. “You’d have to actually believe them to be scared,” says Rummel. “There are many unanswered questions about what Elon Musk wants to do. But I think we can calm down about people showing up on Mars unannounced.”

But SpaceX has defied expectations before and may give slow and steady a kick in the pants.

This article appears in the January 20, 2018 issue of Science News with the headline, “Mucking up Mars: Microbes from Earth may complicate human junkets to the Red Planet .”

Editor’s note: This story was updated on January 11, 2018 to include recent findings about water ice from Colin Dundas and his team.