In the darkest, deepest part of the ocean, microscopic life thrives under extreme pressures and isolation from the world above. Surprisingly, bacteria in the West Pacific’s Challenger Deep gobble up more oxygen than does the life in a nearby shallower area, researchers report March 17 in Nature Geoscience.

The study shows the ability of some microbial life to make the most of a difficult environment, says Tim Shank of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, who was not involved in the study. “They had to evolve to live there,” Shank says. He wonders whether the adaptations necessary to live in the ocean’s deepest spot first emerged in the trenches or if microbes evolved their deep-sea capabilities while living in shallower waters and subsequently moved down.

Pressures at the ocean’s deepest points are high enough — more than 1,000 times those at sea level — to flatten a person. Scientists didn’t know what sorts of life could survive in those conditions and how metabolically active it could be. Such deep areas are difficult to visit and study directly.

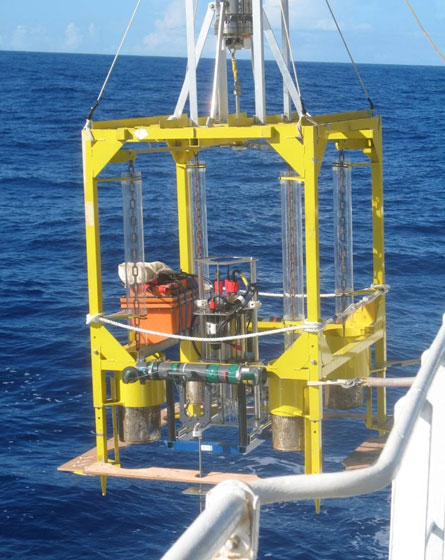

In 2010, researchers led by Ronnie Glud of the University of Southern Denmark sent an unmanned, remotely operated deep-sea lander to the western Pacific Ocean to explore the Mariana Trench’s Challenger Deep—a valley 11 kilometers down, the deepest seafloor on Earth. It also visited a nearby site 6 kilometers down. The researchers encased key instruments in a pressure-resistant titanium cylinder. The motor and other mechanical parts were immersed in a fluid with a balloon that could adjust the pressure to match the surrounding punishing pressure, Glud says.

The lander indirectly measured microbial activity in the sediments by studying how much oxygen the microbes used up while digesting food. Oxygen consumption rates were two times and bacterial density nearly 10 times those in the shallower area, the researchers found.

Another surprise was that the trench’s residents receive a healthy supply of food. Scientists had believed that, compared with shallow parts of the ocean, deep areas get far less organic matter. But compared with the shallower area, the Challenger Deep had about 25 percent more organic matter in its sediments. The carbon-rich material, likely dead organisms such as fish and algae, had floated down from above, Glud says.

The material could have been jostled down to deep trenches as a result of geological processes such as earthquakes. “It’s kind of like a funnel,” Glud says.

Glud expects that other deep-sea trenches may harbor similarly large and active microbe communities. Researchers also need to better understand which deep-sea trenches get a lot of carbon and how that happens, Shank says.

Further research on those questions is important given that oceans exchange carbon with the atmosphere. Deep-sea microbes alter that exchange because they turn organic matter into carbon dioxide, a key greenhouse gas.