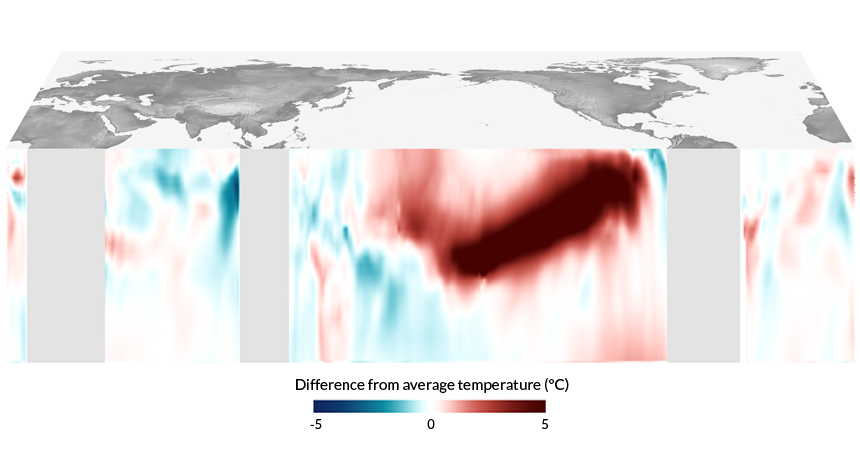

LUKEWARM Warm water (red) in the Pacific Ocean sloshed eastward this spring, prompting many scientists to expect a strong 2014 El Niño. The bottom of the image shows a vertical cross section of seawater temperatures in mid-April; the warm pool extends roughly 100 meters deep off South America’s coast.

Dan Pisut/Climate Prediction Center/NOAA Climate.gov

California won’t see hoped-for relief from drought this winter, scientists say, because El Niño is likely to be weak or nonexistent.

Earlier this year, many scientists anticipated a blockbuster 2014 El Niño that would rival the record-setting 1997 event. That year’s El Niño — a climate disruption generated by unusually warm seawater in the eastern Pacific Ocean — triggered severe weather worldwide, including storms and floods on the West Coast and droughts in Southeast Asia. But now the Climate Prediction Center of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration projects that a strong El Niño is unlikely and the chances of even a mild one forming have dwindled to around 60 percent.

A lack of wind gusts over the Pacific Ocean left this year’s El Niño dead in the water, researchers propose September 26 in Geophysical Research Letters. Scientists think these winds push warm seawater eastward, which in turn rises to the ocean surface along South America’s coast and heats the atmosphere, causing dramatic shifts in weather.

“If we had the same series of wind events in 2014 as we had in 1997, we would have gone strongly toward an El Niño state,” says study coauthor Jérôme Vialard, a climate scientist at the Laboratoire d’Océanographie et du Climate – Expérimentation et Approches Numériques in Paris.

An oblong pool of warm seawater more than 14,000 kilometers wide always blankets the West Pacific. During the first few months of 1997 and 2014, this warm pool shifted east as the westward trade winds slackened.

The similarities between the two periods “set off an alarm within the community,” says study coauthor Christophe Menkes, a climate scientist at the Institute of Research for Development in New Caledonia, a self-governing French territory in the southwestern Pacific. The 1997 El Niño killed an estimated 22,000 people and caused roughly $36 billion in economic losses. However, in July 2014 unlike in 1997, the warm pool in the Pacific swung back to its normal position before rising to the ocean surface, decreasing the chance of a full-blown El Niño.

Menkes believes El Niño conditions fell flat this year because wind gusts called antitrade winds stopped blowing in April. These eastward gusts, Menkes says, would have helped lock the warm pool in place after it shifted into the East Pacific.

To determine whether the missing gusts were the key difference between the 1997 and 2014 seasons, Menkes, Vialard and colleagues did a virtual wind swap. Using computer simulations of the Pacific, the team calculated how 2014 El Niño conditions would have progressed under the wind patterns observed in 1997.

The warm pool would probably have stayed in the east and not have retreated westward, the team found, significantly boosting the possibility of a strong 2014 El Niño event. The results indicate that if the antitrade winds don’t return, Vialard says, “this year’s El Niño is more or less dead.”

And that’s bad news for the West Coast. California is in the midst of one of the most severe droughts on record and multiple large wildfires raged across the state this summer. Many had hoped El Niño would bring much-needed water to the region, which has received only 55 percent of normal precipitation so far this year.

The root cause of this year’s El Niño dud remains unknown, says Michelle L’Heureux, a climate scientist for NOAA in College Park, Md. “The big question is why the winds weren’t as strong and rigorous as they were in 1997,” she says. Winds are difficult to forecast, L’Heureux explains, and contribute randomness into El Niño development and make the events difficult to predict.

The uncertainty in part stems from the winds being influenced by atmospheric and oceanic conditions elsewhere on Earth, says climate scientist Kevin Trenberth of the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo. The presence or absence of antitrade winds, he says, may be a by-product of the overall atmospheric changes that prompt El Niño as much as they are a cause.