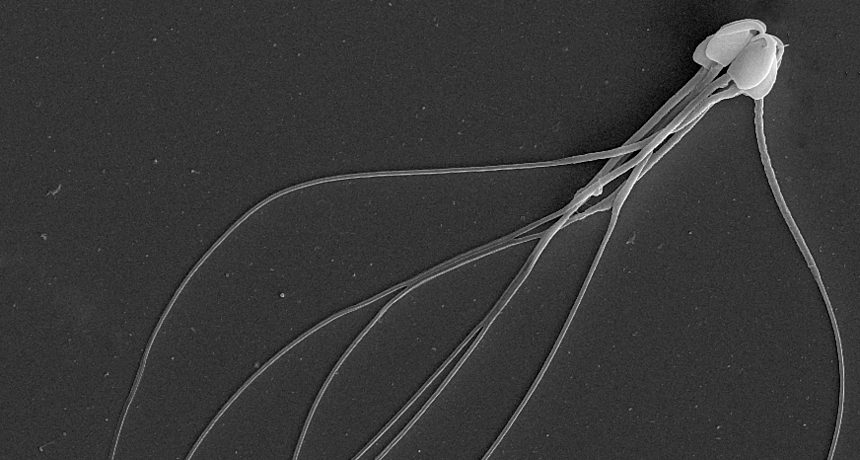

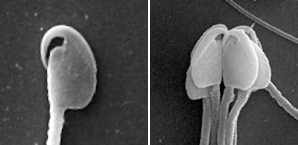

SPERM CREW Traveling in a straight line comes easier for groups of sperm than for solo swimmers in two mouse species.

© James Weaver/Wyss Institute/Harvard Univ.

Mouse sperm shoot along straighter paths by ganging up. Yet the merits of forming flocks evaporate if the group becomes too large, researchers report July 22 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

“Sperm aggregation is one of the more enigmatic adaptations to sperm competition,” says evolutionary biologist Dawn Higginson of the University of Arizona in Tucson.

Sperm competition arises when a female mates with multiples males, and though cooperative behavior in sperm is rare, examples appear across the animal kingdom — from great diving beetles to possums. Controversy looms over whether sperm herding provides a competitive advantage over swimming solo. In desert ants (SN: 7/26/14, p. 20) and Norway rats, sperm crews swim faster, but in some species like the house mouse, packs are actually slower.

This discrepancy led evolutionary biologist Heidi Fisher and her colleagues at Harvard University to look closely at sperm groupings in two closely related mouse species. The researchers sprayed sperm onto a microscope slide and videotaped the scene as the squigglers gathered into parties and swam across the slide. The team found that sperm groups don’t drive faster than lone swimmers do. Instead of boosting overall speed, the groups travel with better velocity, meaning they move with a straighter trajectory and therefore get to their destination more quickly.

Promiscuity influenced sperm dynamics as well in the two species the researchers examined: the monogamous beach mouse (Peromyscus polionotus) and the North American deer mouse (P. maniculatus), which shares multiple partners.

In lab tests, sperm from the promiscuous species formed the optimum size for pack travel more often than did monogamous mice. Because sperm from different males face off inside the genital tracts of female P. maniculatus mice, the greater tendency toward pack behavior in this species may represent an adaptation to more competition, Fisher says. She and a colleague previously reported that P. maniculatus sperm join forces only if they come from the same male. Both discoveries signal a finely tuned scheme for besting challengers while racing toward an egg, Fisher says.

To verify these sperm dynamics in a more natural setting, says reproductive biologist William Breed of the University of Adelaide in Australia, Fisher’s team could examine the reproductive tracts of female mice soon after the rodents mate.