From viruses to elephants, nature thrives on tiled patterns

A new catalog shows how organisms use mosaics for protection, movement and more

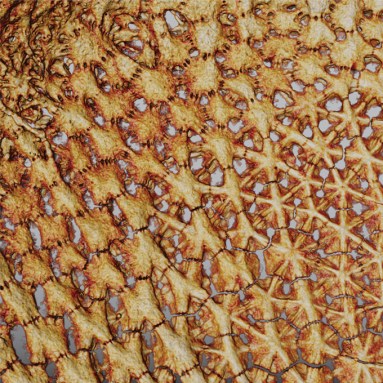

The compound eyes of the snipe fly and many other insects are tessellated with ommatidia, which individually capture images that are then compiled by the insect’s brain into a single picture.

lauriek/Getty Images

This is a human-written story voiced by AI. Got feedback? Take our survey . (See our AI policy here .)