Nerve cell migration after birth may explain infant brain’s flexibility

Frontal lobe development influenced by cellular latecomers, study finds

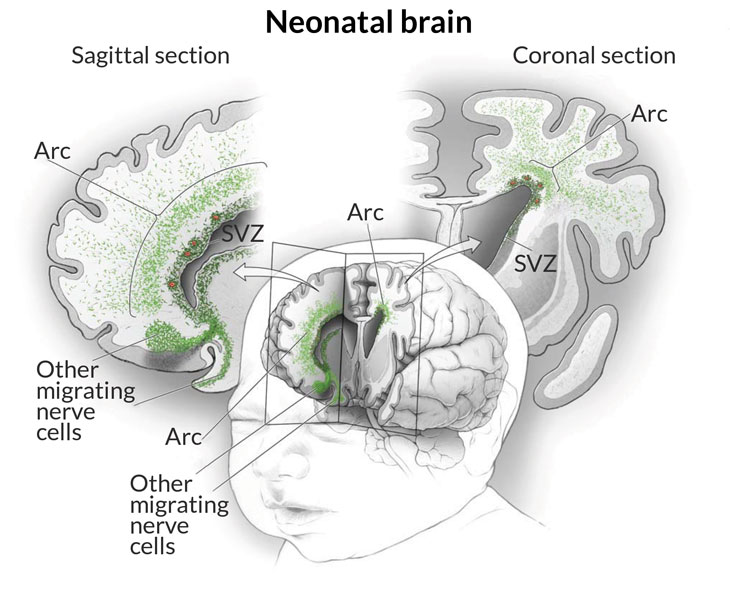

BABY BRAIN New nerve cells in infants’ brains migrate to the frontal lobe after birth, where they help regulate other neural messages.

Vasilyev Alexandr/Shutterstock

Baby humans’ brain cells take awhile to get situated after birth, it turns out. A large group of young nerve cells moves into the frontal lobe during infants’ first few months of life, scientists report in the Oct. 7 Science. The mass migration might help explain how human babies’ brains remain so malleable for a window of time after birth.

Most of the brain’s nerve cells, or neurons, move to their places in the frontal lobe before birth. Then, as babies interact with the world, the neurons link together into circuits controlling learning, memory and social behavior. Those circuits are highly malleable in early infancy: Connections between neurons are formed and severed repeatedly. The arrival of new neurons during the first few months of life could help account for the circuits’ prolonged flexibility in babies, says study coauthor Eric Huang, a neuropathologist at the University of California, San Francisco.

“The fact that [the neurons] are migrating for months and months is remarkable,” says Stephen Noctor, a neuroscientist at the University of California, Davis who wasn’t involved in the work.

Huang and colleagues noticed a group of cells making proteins related to migration when looking at slices of postmortem infant brains under an electron microscope. To catch these neurons in the act of moving, though, the team used rare samples of brain tissue collected and donated immediately after infants’ deaths. The team infected those tissues with a virus tagged with a glowing protein. When the virus infected the brain cells, they glowed green. Then the researchers could track the migrating neurons’ path across the brain.

Nerve cells on the move

A group of neurons (shown in green) starts out in the subventricular zone (SVZ) and migrates outward in an arc towards the surface of the frontal lobe. Some of them also cluster around blood vessels (shown in red).

The neurons started as a cluster in the subventricular zone, a layer inside the brain where new neurons are born, and then formed a chain moving into the frontal lobe, Huang’s team found. Once the migrating neurons settled down later in development, they mostly became inhibitory interneurons. This type of neuron acts like a stoplight for other neurons, keeping signaling in check.

Huang’s team found migrating neurons in the brains of babies up to about seven months old, with migration peaking around 1.5 months and then tapering off.

“In the first six months, that’s kind of [infants’] critical period when they slowly develop their response to [their] environment. They start to engage with emotions,” says Huang. “Our results provide a cellular basis for postnatal human brain development and how cognition might be developed.”

By replenishing the frontal lobe’s supply of building blocks midway through construction, the new neurons might help babies’ brain circuits stay malleable longer. The mass migration after birth means that experiences in infancy could affect where these neurons end up — and, by extension, the connections they form.

The finding raises additional questions about the timing of the event, Noctor says — like when the migrating cells were born and how long an individual cell takes to move.