Nerve cells that help control hunger have been ID’d in mice

Targeting similar cells in people could mark a new way to regulate appetites

HUNGER SIGNS Certain nerve cells in a mysterious brain region in mice become active when the mice are hungry (yellow spots at left) and when the hunger hormone ghrelin is present (yellow spots at right), microscope images show.

S.X. Luo et al/Science 2018

Newly identified nerve cells deep in the brains of mice compel them to eat. Similar cells exist in people, too, and may ultimately represent a new way to target eating disorders and obesity.

These neurons, described in the July 6 Science, are not the first discovered to control appetite. But because of the mysterious brain region where they are found and the potential relevance to people, the mouse results “are worth pursuing,” says neurobiologist and physiologist Sabrina Diano of Yale University School of Medicine.

Certain nerve cells in the human brain region called the nucleus tuberalis lateralis, or NTL, are known to malfunction in neurodegenerative diseases such as Huntington’s and Alzheimer’s. But “almost nothing is known about [the region],” says study coauthor Yu Fu of the Singapore Bioimaging Consortium, Agency for Science, Technology and Research.

In people, the NTL is a small bump along the bottom edge of the hypothalamus, a brain structure known to regulate eating behavior. But in mice, a similar structure wasn’t thought to exist at all, until Fu and colleagues discovered it by chance. The researchers were studying cells that produce a hormone called somatostatin — a molecular signpost of some NTL cells in people. In mice, that cluster of cells in the hypothalamus seemed to correspond to the human NTL.

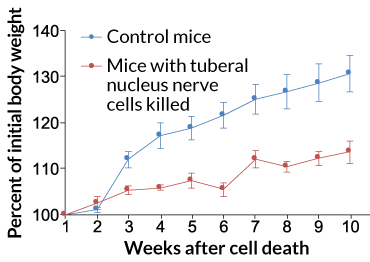

Not only do these cells exist in mice, but they have a big role in eating behavior. The neurons sprang into action when the mice were hungry, or when the hunger-signaling hormone ghrelin was around, the team found. And when the researchers artificially activated the cells, using either laser light or molecular techniques, the mice ate more and gained weight faster than normal mice. Conversely, when the researchers killed the neurons, the mice didn’t eat as much and gained less weight than mice that still possessed the cells. The results suggest that, in mice, these neurons influence the impulse to eat — and subsequent changes in weight.

More experiments need to be done to study whether the cells behave similarly in people, Diano cautions.

Both Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s have been tied to metabolic problems and changes in appetite. The demise of appetite-controlling cells in the NTL might help explain why.

If NTL cells do control appetite in humans, that brain region wouldn’t be working alone. Far from it. Neighboring nerve cells in and around the hypothalamus are also known to play big roles in prodding the body to eat when food is available (SN Online: 5/25/17). “Our bodies were built to make sure we will eat whenever we have the chance,” Fu says.

For many people, high-calorie foods are now easy to come by. “When suddenly we are faced with food abundance, our bodies simply can’t cope with it,” Fu says. The result can be metabolic disorders, such as obesity. Tweaking the behavior of these appetite-controlling cells, perhaps with drugs, may one day offer a way to treat obesity or eating disorders such as anorexia (SN: 3/7/15, p. 8).