Obscure brain region linked to feeding frenzy in mice

Optogenetics reveals a possible role in binge eating for nerve cells in zona incerta

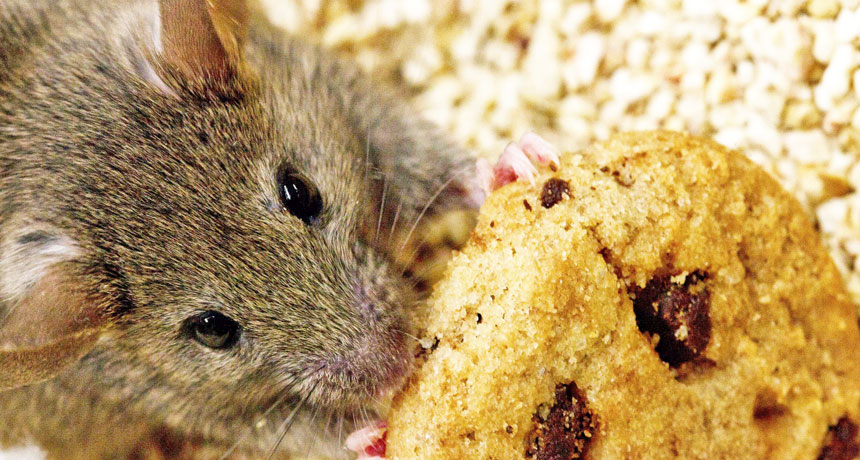

CHOW TIME When scientists used light to stimulate select nerve cells in a region of the brain called the zona incerta, mice began eating voraciously. The results suggest that the little-studied brain region may have a role in eating behavior.

Anthony van den Pol

Nerve cells in a poorly understood part of the brain have the power to prompt voracious eating in already well-fed mice.