A newly found Atacama Desert soil community survives on sips of fog

Lichens and other fungi and algae unite to form this ‘grit-crust’ on parched soil

Scientists have discovered a hardy form of biological soil crust that survives on coastal fog in northern Chile. This “grit-crust” creates black and white splotches across the land in Pan de Azúcar National Park (shown).

P. Jung

By Jack J. Lee

- More than 2 years ago

Read another version of this article at Science News Explores

Perhaps the hardiest assemblage of lichens and other fungi and algae yet found has been hiding in plain sight in northern Chile’s Atacama Desert.

This newly discovered “grit-crust,” as ecologists have named it, coats tiny stones and draws moisture from daily pulses of coastal fog that roll across the world’s driest nonpolar desert. These communities are optimized to photosynthesize using less than half of the water that other known desert biological soil crusts use, researchers report in the January Geobiology.

The “super cool” find suggests that soil communities can eke out a living in the planet’s harshest settings, says Jayne Belnap, a U.S. Geological Survey ecologist based in Moab, Utah, who was not involved in the study.

Biological soil crusts, or biocrusts, are conglomerations of algae, cyanobacteria, lichens, fungi or mosses that cover an estimated 12 percent of the land on Earth. They are commonly found in deserts, where they blanket the soil and prevent erosion. They also shape ecosystems by drawing atmospheric carbon and nitrogen into the ground and producing oxygen via photosynthesis.

Only a few millimeters of rain dampen the Atacama on average each year. But some areas experience daily cycles of fog and dew. In one such “fog oasis,” about 2.5 kilometers from the Pacific Coast in Pan de Azúcar National Park north of Santiago, researchers spotted odd markings.

“We got there with our cars and saw these blackish and whitish patterns in the landscape,” says botanist Patrick Jung of Hochschule Kaiserslautern – University of Applied Sciences in Germany.

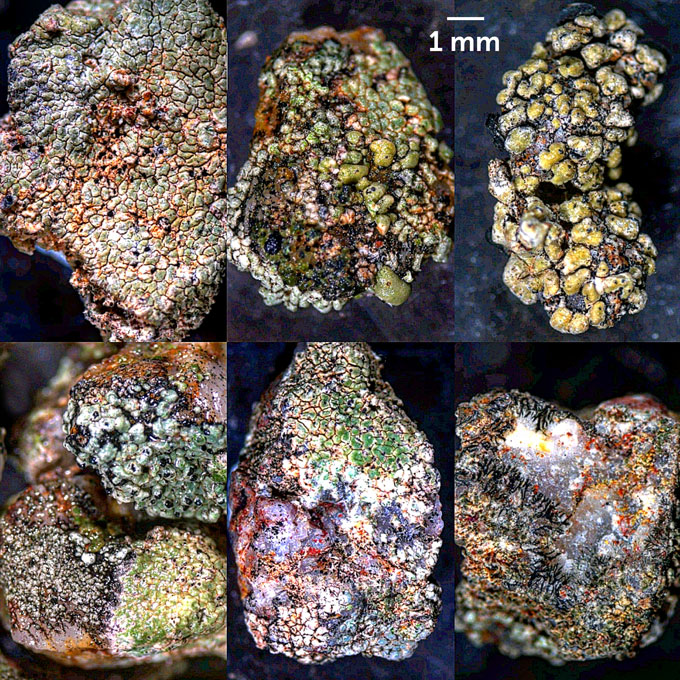

Previous surveys have identified other biocrusts in the Atacama. But the new crust samples weren’t like those — analyses revealed lichens, fungi, algae and cyanobacteria enveloping tiny, 6-millimeter pebbles and keeping the pebbles stuck together atop the soil, like a rock-based peanut brittle. Unlike other biocrusts, which form on soil surfaces, grit-crust is “something different that we’ve not seen before,” says Matthew Bowker, an ecologist at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff not involved in the study.

In lab experiments, the team measured the rate at which the crust collectives consumed carbon dioxide with varying amounts of moisture. Photosynthetic activity peaked when a sample had just 0.25 millimeters of water — equivalent to 250 milliliters of water for one square meter of grit-crust — which is within the range expected for deposits from daily fog banks near the coast. By comparison, biocrusts in the Sonoran Desert in Mexico and the U.S. Southwest are most photosynthetically active when saturated with between 0.5 and 1 millimeter of water.

Detailed microscopy of the rocks showed fungi associated with the grit-crust tunneling in from the surface. These fungi’s tubular growth structures, or hyphae, swell and shrink with the flow of fog, creating cracks that eventually break up the stones. This “biological weathering” is the only known process to create new soil in the Atacama Desert, the team says. Such grit-crusts may have transformed the harsh surface of ancient Earth before photosynthesizing plants arose by breaking down stones and contributing to nutrient cycling (SN: 3/1/18).

While scientists have documented both fungi and plants burrowing into rock (SN: 5/22/19), as well as lichens surviving in fog deserts (SN: 2/27/18), grit-crust represents “a novel composite of those processes,” Belnap says.

Similar crusts probably grow in Earth’s other fog deserts, Jung says. The researchers plan to search for communities in the coastal Namib Desert in southern Africa, where others have spotted the telltale black-and-white patterns.