DIG IT Collecting a sample of Barbacenia macrantha (shown) is tough work, requiring chisels and hammers to unearth the plant and the rock it grows in. The plant’s specialized roots help it live in environments deficient in phosphorus and other nutrients.

A. Abrahão

No soil? No problem. Some herbaceous shrubs living on rocky mountains in Brazil use roots equipped with fine hairs and acids to dissolve rocks and extract the key nutrient phosphorus. The discovery, published in the May Functional Ecology, helps explain how a variety of plants can survive in impoverished environments.

“While most people tend to view nutrient-poor environments as less diverse, they are actually very diverse because plants use diverse ways to get nutrients,” says coauthor Patricia de Britto Costa, a plant ecologist at the University of Campinas in Brazil.

She and other colleagues in Brazil and Australia investigated how shallow-soil regions called campos rupestres in Portuguese, or rocky grasslands, can sustain more than an estimated 5,000 plant species — 15 percent of Brazil’s vascular plant diversity — despite occupying less than 1 percent of the country’s land area. What soil there is in these regions is poor, with nearly undetectable levels of the nutrients that plants need. And some plants manage to survive on rocky patches with no soil.

Researchers used chisels and hammers to dig up the plants. “We found the roots growing into the rocks,” at least 10 centimeters deep, says coauthor Anna Abrahão, a plant ecologist now at the University of Hohenheim in Stuttgart, Germany. “The roots go deeper, and we always lose some of them.”

The root issue

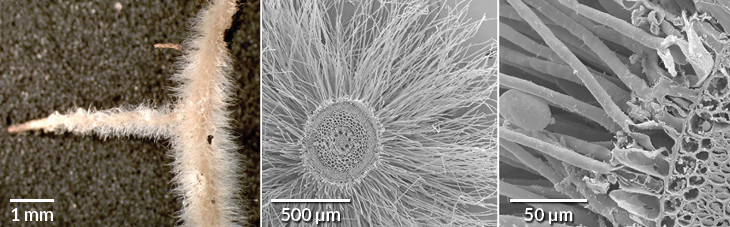

Barbacenia tomentosa plants have densely packed fine hairs that grow near their root tips (left). Those hairs (seen in the scanning electron micrograph image at middle) likely secrete acids that dissolve rock to release a key nutrient. A related plant called B. macrantha has similar roots (one shown in the scanning electron micrograph image at right)

Microscopic and chemical analyses of 30 specimens of two herbaceous plant species living on quartzite rocks — Barbacenia tomentosa and B. macrantha, both of the Velloziaceae family — revealed specialized segments of densely packed hairs just behind the root tip. The roots secrete malic and citric acids, likely from the fine hairs, that dissolve rock and release phosphates that the roots then absorb to get the nutrient phosphorus. Microscopy scans suggest that the roots carve their own way into rocks, rather than growing along cracks. The scientists named these structures vellozioid roots, after the plants’ family name.

These roots, found only in these two species so far, are the first known to dissolve rocks, the team says. But the work has inspired plant physiologist Alex Valentine of the University of Stellenbosch in South Africa, who was not involved in the study. He now plans to search for such roots in Velloziaceae plants in South African mountain regions.

Home sweet home

Barbacenia tomentosa (left) and B. macrantha (middle) plants grow in rocky outcrops in Brazil. The plants have hardy roots that carve tunnels in the rock (shown in this microscope image at right, arrows) to access nutrients needed to survive.

Plants living in other phosphorus-poor environments around the world have evolved either cluster roots or dauciform roots, with dense root hairs and acid secretions to harvest phosphorus from poor soils and sand, but not actual rock. Vellozioid roots use the same strategy “in an entirely new way,” by “dissolving rocks and forming new sand,” Valentine says.

Quartzite rocks in Brazil’s rocky grasslands have especially low levels of phosphorus, the study found. On average, each gram of rock contains only 0.14 milligrams of the nutrient. By comparison, the lowest level found in a 2013 survey of 69 rock types worldwide was an average of 0.12 milligrams in peridotite rocks.

Further research into vellozioid roots might one day help develop more efficient crops. “If we can transfer these traits to crops,” Valentine says, “it means that crops can grow in rocky or sandy soils.”