Ultima Thule may be a frankenworld

Astronomers are closer to uncovering the distant space rock’s origin story

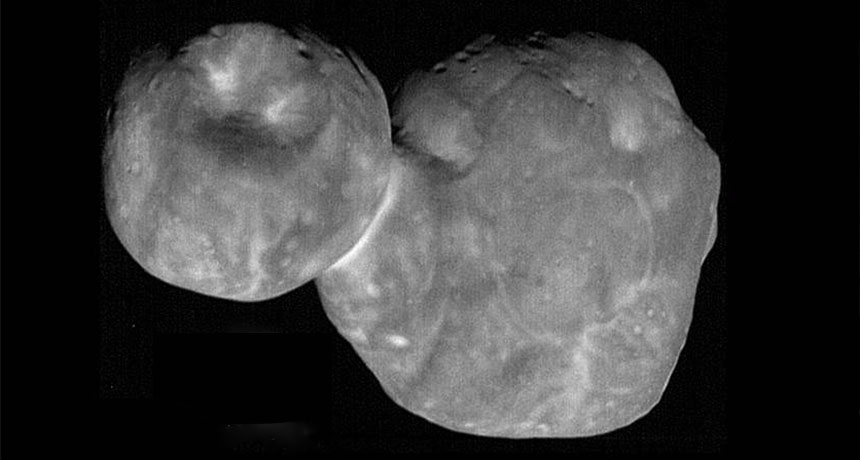

SLOW SMASH The two lobes of Ultima Thule probably came together at the speed of a person walking briskly into a wall, researchers announced.

NASA, JHU Applied Physics Laboratory, Southwest Research Institute, ESA