Our fascination with robots goes all the way back to antiquity

‘Gods and Robots’ explores how ancient people thought about artificial life

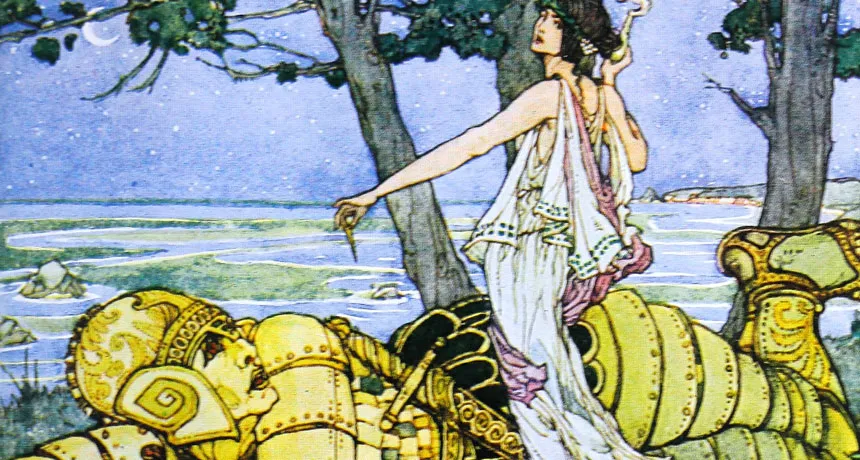

MYTHIC AI Ancient myths wrestled with basic questions about artificial life long before the current explosion of artificial intelligence machines. Here, the cunning sorceress Medea destroys an android guardian named Talos in the culmination of a Greek myth.

Sybil Tawse/Wikimedia Commons