Perfect Match: Embryonic stem cells carry patients’ DNA

Made-to-order stem cells that genetically match a patient’s own tissues could provide a perfect patch for replacing cells damaged by injury or disease. This approach would avoid immune rejection (SN: 4/2/05, p. 218).

By priming embryonic cells with genetic material derived from people with problems that stem cells may one day treat, researchers have isolated 11 new lines of stem cells that exactly match the patients’ own DNA.

Therapeutic cloning, which yields stem cells that can be used to treat patients, differs from reproductive cloning, which creates a new organism. However, the two types of cloning use many of the same techniques. Scientists start by removing an egg’s nucleus, which carries most of a cell’s genetic material. They then inject the egg with a nucleus from a donor cell, such as a skin cell. After the cell divides and grows into a multicelled embryo, researchers doing therapeutic cloning extract stem cells that carry the same genetic signature as that of the donated nucleus.

Until recently, researchers’ ambitions were hampered by difficulties in creating clones of human cells. Last year, a team led by Woo Suk Hwang at Seoul National University in South Korea succeeded in making the first human clone and in isolating stem cells from it (SN: 2/14/04, p. 99: Tailoring Therapies: Cloned human embryo provides stem cells).

However, Hwang’s team created the clone using an egg and an ovarian cell from a young woman, and some scientists were doubtful that the technique would work for cloning cells from men or older women.

In a new study, Hwang and his colleagues proved those skeptics wrong by cloning cells from 11 female and male patients ranging in age from 2 to 56. All the study participants suffered from spinal cord injuries, juvenile diabetes, or hypogamma-globulinemia, a genetic disease that causes an immune deficiency. Scientists have proposed that therapeutic cloning might someday treat all three conditions.

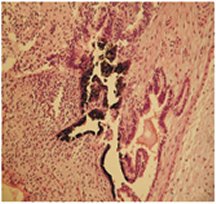

Starting with 185 donated eggs, the researchers successfully created 31 embryos carrying DNA from the various patients. Embryos representing 9 of the 11 patients yielded stem cells that survived in a lab culture. Hwang’s team found that the stem cells and the patients’ original cells have the same markers that the immune system uses to distinguish self from foreign cells. After several weeks, clumps of the new stem cells grew into different tissue types, showing that they can create many of the body’s different cells, the researchers assert.

Hwang and his colleagues report these results in the June 17 Science.

One of the team’s most important results, notes Rudolph Jaenisch of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research in Cambridge, Mass., is the improved efficiency over last year’s cloning experiment. The team’s previous experiment resulted in only one line of stem cells out of 30 embryos, about one-tenth the efficiency of the scientists’ most recent efforts.

The findings could give U.S. scientists lobbying power to secure government funding for similar experiments, says Douglas Melton of Harvard University. Right now, the U.S. government funds only experiments that use 20 or so existing lines of embryonic stem cells.

“It’s a little more than frustrating to watch the United States cede the lead in exciting areas of science because we’re hampered here in our ability to move forward,” says Melton.

Although the new stem cells may eventually be used to treat the patients from whom they were cloned, study coauthor Gerald Schatten of the University of Pittsburg School of Medicine says that a more immediate use will be for studying genetic diseases. Tracking how the cells differ from stem cells cloned from healthy people may give scientists clues to developing new drugs.