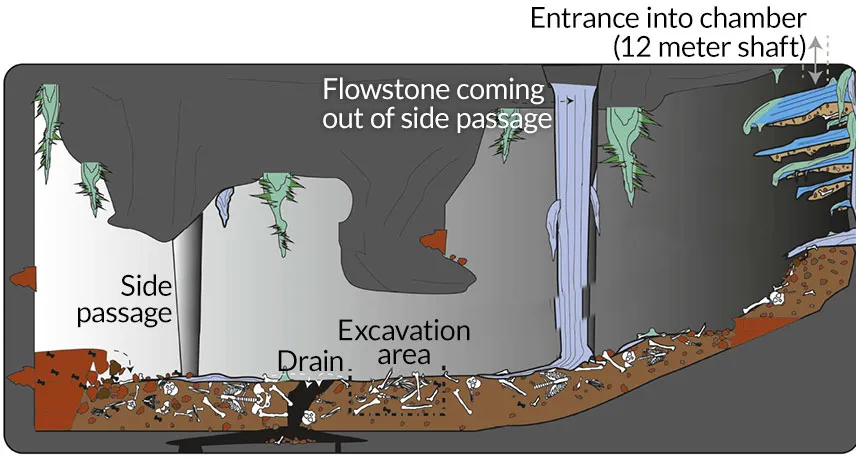

DEEP EVOLUTION Homo naledi fossils were found in South Africa’s Dinaledi Chamber, outlined here. Researchers debate whether this species dropped its dead through a shaft into the underground space, creating the array of bones shown on the chamber floor.

P.H.G.M. Dirks et al/eLife 2015 (CC BY 4.0)

ATLANTA — Homo naledi, a rock star among fossil species in the human genus, has made an encore. Its return highlighted debate over whether this hominid was a distinct Homo species that purposefully disposed of at least some of its dead.

H. naledi made worldwide headlines last year when researchers announced the discovery of an unusually large collection of odd-looking Homo fossils in the bowels of a South African cave system. Presentations at the annual meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists on April 16 underscored key uncertainties about the hominid.

One of the biggest mysteries: H. naledi’s age. Efforts are under way to date the fossils and sediment from which they were excavated with a variety of techniques, said paleoanthropologist John Hawks of the University of Wisconsin–Madison. An initial age estimate may come later this year if different dating techniques converge on a consistent figure. A solid date for the fossils is essential for deciphering their place in Homo evolution and how the bones came to rest in a nearly inaccessible cave.

Some presenters reasserted that H. naledi intentionally dropped dead comrades into an underground chamber, where their bones were later found by cave explorers and then scientists. But others raised questions. Even paleoanthropologist and team leader Lee Berger of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg hedged his bets.

“It’s way too early to tell how H. naledi bodies got in the chamber,” Berger said.

Berger’s group recovered 1,550 H. naledi fossils from a minimum of 15 individuals of all age groups (SN: 10/3/15, p. 6). Slender researchers wended through narrow passageways in South Africa’s Rising Star cave system and squeezed down a vertical chute to reach pitch-dark Dinaledi Chamber. There, they found hominid fossils scattered on the floor and in a shallow, 20-centimeter-deep excavation.

Berger’s team assigned the bones to H. naledi based on an unexpected mix of humanlike features and traits typical of Australopithecus species from more than 3 million years ago.

Fossil analyses presented at the meeting challenged a suggestion by some researchers, both before and during the meeting, that H. naledi actually represents a variant of Homo erectus, a species known to have existed by 1.8 million years ago (SN: 11/16/13, p. 6).

H. naledi possessed a shoulder unlike those of other Homo species, said team member Elen Feuerriegel of the Australian National University in Canberra. The Rising Star hominid’s collarbone and upper arm bone resemble corresponding Australopithecus bones, she reported. H. naledi’s shoulder blades must have been positioned low and behind the chest, an arrangement more conducive to climbing trees than running long distances.

H. naledi’s hand was built both for climbing and gripping stone implements, said Tracy Kivell of the University of Kent in England. Her analysis of 150 hand bones, including a nearly complete hand, showed a humanlike wrist and thumb combined with Australopithecus-like curved fingers.

H. naledi’s curved toes and flaring pelvis also recall Australopithecus. Still, a preliminary lower-body reconstruction — incorporating fossil evidence of humanlike legs, knees and feet — suggests H. naledi walked almost as well as modern humans do, said Zach Throckmorton of Lincoln Memorial University in Harrogate, Tenn.

West Asian H. erectus and H. naledi share several tooth features as well as relatively small braincases. In addition, adult H. naledi stood an estimated 147 centimeters tall (4 feet, 10 inches), within the height range for West Asian H. erectus. “That complicates matters,” said Christopher Walker of Duke University. Upper-body features that Berger’s team considers characteristic of H. naledi, such as the upper arm’s shape, possibly occurred in West Asian H. erectus as well, added Witwatersrand’s Tea Jashashvili, who has studied those finds.

Explaining how H. naledi bones ended up in Dinaledi Chamber is also complicated. Ongoing studies of sediment and rock indicate that there was never a direct opening to the underground fossil site from above, said Witwatersrand’s Marina Elliott.

Bones from some body parts, including five feet, three hands and part of a backbone, were found aligned as they would have been in living individuals, indicating at least some bodies reached the chamber intact, Hawks said. Curiously, some sets of aligned bones were found beneath scattered bones from diverse individuals.

If the dead were dropped down a vertical chute into Dinaledi Chamber, bodies on top would have been least damaged and most likely to retain aligned bones. Along with that mystery, some sets of aligned bones somehow ended up far from the chute’s opening, Berger said.

An alternative entrance to Dinaledi Chamber possibly existed in the past, Witwatersrand’s Aurore Val asserted online March 31 in the Journal of Human Evolution. Beetles or snails that damaged some H. naledi bones don’t inhabit dark, underground caves, Val argues. Such damage probably occurred on the surface or in a nearby, once-accessible part of the cave system, she proposes.

The surfaces of many H. naledi fossils had been worn down enough to have possibly erased predators’ tooth marks and signs of animal trampling, which would be additional signs that another entrance to the chamber once existed, Val says.

Given the large number of isolated and broken H. naledi fossils, bodies or body parts may have entered the chamber long after death, in Val’s view. Perhaps water from another part of the cave system carried bodies into Dinaledi Chamber, she speculates.

Geologic studies show that water occasionally reached the chamber and mildly eroded sediment, Berger said. But he doubts water washed bones into Dinaledi Chamber. “Even if there was another entrance to the chamber, it still allowed access only to Homo naledi,” Berger argued. No remains of any other animals have been found in the cave.

Like any rock star of lasting impact, the South African hominid plans to wow fans with new material. “Thousands of Homo naledi fossils are almost certainly left in the underground chamber,” Berger said.

Editor’s note: This story was updated April 25, 2016, to correct the identification of organisms that have damaged some H. naledi bones.