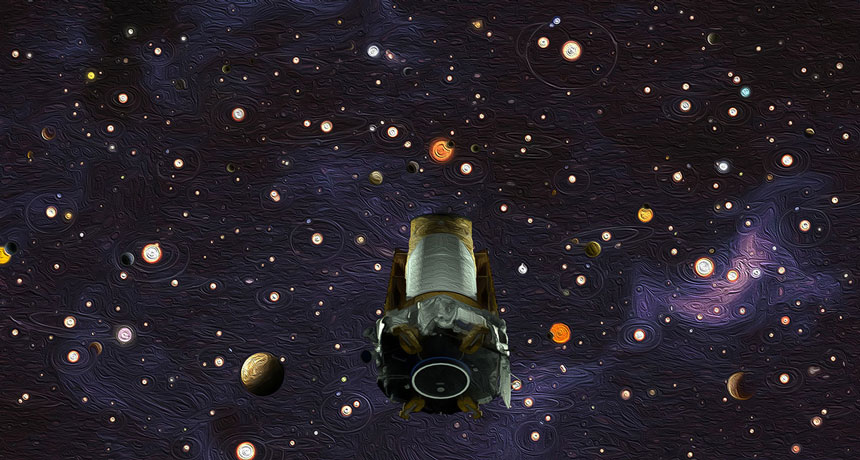

KEPLER'S CURTAIN CALL NASA’s Kepler space telescope, shown in this artist’s illustration, found thousands of planets orbiting other stars.

NASA

NASA’s premier planet-hunting space telescope is out of gas.

The Kepler space telescope can no longer search for planets orbiting other stars, ending its nearly 10-year mission, officials from the agency announced in a news conference on October 30.

“Because of fuel exhaustion, the Kepler spacecraft has reached the end of its service life,” said Charlie Sobeck, a project system engineer at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif. “While this is a sad event, we are by no means unhappy with this remarkable machine.”

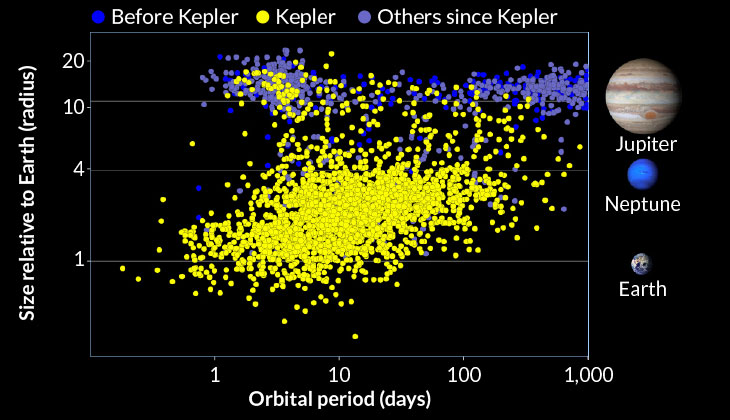

Kepler’s discoveries have forever changed the way astronomers think about planets in other solar systems. Before the spacecraft launched in 2009, only about 350 exoplanets were known to exist in the galaxy, and nearly all of them were the size of Jupiter or larger.

As of October 30, there are more than 3,800 known exoplanets, and Kepler was responsible for discovering 2,720 of them. The spacecraft found planets in all shapes, sizes and configurations: seven planets orbiting one star, planets orbiting at jaunty angles, planets with two suns, planets more than twice as old as Earth. “These planets formed at the beginning of the formation of our galaxy,” says astronomer William Borucki, who was Kepler’s principal investigator until he retired in 2015. “Imagine what life might be like on such planets.”

What’s more, astronomers have used Kepler’s exoplanet haul to predict that every one of the hundreds of billions of stars in the Milky Way should have at least one planet, on average (SN: 2/25/12, p. 12). And billions of those exoplanets’ sizes and temperatures, scientists think, might make them friendly to life (SN: 11/30/13, p. 13).

Planets, planets everywhere

The Kepler space telescope launched in 2009. By the end of 2017, it had discovered more than 2,500 planets (yellow), about 70 percent of all exoplanets known. Known exoplanets range in sizes, from those comparable with Earth to the sizes of Neptune or Jupiter or even larger.

Exoplanet discoveries

Kepler was declared dead once before. In 2013, the telescope lost the use of a second of its four reaction wheels, which helped keep the telescope pointed steadily at the same patch of the sky. That consistent pointing was crucial for Kepler’s planet-hunting strategy: spotting a slight dip in stars’ light as planets cross in front of them. It seemed like the mission was over (SN: 6/15/13, p. 10).

But engineers soon revived the telescope in a new observing mode, called K2 (SN: 6/28/14, p. 7), which used the pressure of sunlight on Kepler’s solar panels to keep it pointing straight. “I always felt like it was the little spacecraft that could,” said astronomer Jessie Dotson, a Kepler project scientist at NASA Ames. “It always did everything we asked of it, and sometimes more. That’s a great thing to have in a spacecraft.”

Kepler’s official end came two weeks ago, when the telescope’s fuel pressure dropped by 75 percent in a matter of hours, Sobeck said. Before it shut down, Kepler transmitted all of its remaining data back to Earth. “In the end, we didn’t have a drop of fuel left,” he said.

The spacecraft’s legacy lives on. The next planet-hunting telescope, TESS, or the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, launched in April and has already spotted some exoplanets (SN: 5/12/18, p. 7).

For its final acts, the Kepler team will remotely turn off the telescope’s radio transmitters to avoid contaminating airwaves, and turn off protective systems that would turn those transmitters back on.

“The spacecraft will then be left on its own to drift away in a safe and stable orbit around the sun,” Sobeck said.