Priming the elderly for flu shots

Drug that shuts down a potent signaling molecule might boost protection

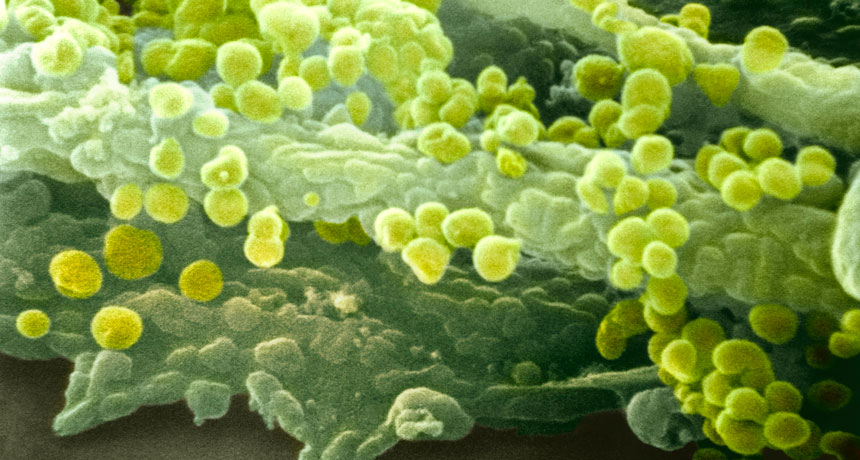

AGENTS OF THE FLU This electron micrograph shows influenza virus particles (round) on a cell membrane.

NIBSC/Science Source

For older people, the sniffling, coughing, fever and aches of the flu aren’t just a nuisance. Influenza infections can turn deadly. Researchers now report a novel strategy for fighting the flu that might improve the odds in this high-risk group.

Low doses of a drug called everolimus taken ahead of a flu shot by people age 65 or older bumped up their immune response to the vaccination by an average of 20 percent, scientists report in the Dec. 24 Science Translational Medicine. Everolimus is commonly given to transplant recipients to fend off rejection and is used to fight certain cancers.

In this early-stage test, researchers sought to determine whether its utility might go further. Previous research with a similar drug in mice improved the animals’ immune protection from a flu shot and extended their survival. The new study attempts to extend those findings to humans, says study coauthor Joan Mannick, an infectious disease physician and researcher at Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research in Cambridge, Mass.

Everolimus is an analog of the drug rapamycin. Both compounds inhibit a powerful signaling protein in cells called mammalian target of rapamycin, or mTOR. While the full role of mTOR in the body is still being unraveled, animal research suggests it can affect immunity.

In humans, immune function declines with age, hurting the response that older people generate to flu shots. So Mannick and her colleagues gave 159 older people everolimus in pill form for six weeks. The volunteers, who lived in Australia or New Zealand, received a low, medium or high dose. Two weeks after completing the drug regimen, each received a flu shot, as did 59 others who hadn’t gotten the mTOR-blocking drug. Four weeks later, blood tests showed that those primed with a low- or medium-sized dose of the drug generated one-fifth more antibodies against the flu than the controls.

“Aside from the potential applications to improve vaccine efficacy in elderly people, this study provides the first good evidence that an mTOR inhibitor can improve at least some aspects of age-related decline in humans,” says Matt Kaeberlein, a molecular biologist at the University of Washington in Seattle who wasn’t involved in the new study. “It’s pretty convincing that this transient treatment with an mTOR inhibitor can have an effect.” But he notes that it remains unknown whether this apparent benefit is specific to flu defense or whether it might apply more broadly.

While recipients primed with a low or medium dose of the drug generated an improved response from the flu shot as a group, a closer look shows a mixed bag of results. For example, the primed volunteers generated a better response to the H1N1 flu component of the shot by some measurements but not by others. The same variable response showed up against the H3N2 flu strain. Curiously, people with little standing immunity to the flu upon entering the study seemed to benefit the most from the primer drug regimen.

“I think a good deal more work is required before using a rapamycin analog routinely to boost flu vaccine responses,” says chemist David Harrison of the Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine, also not involved in this study.

The authors agree. “This was just our first baby step to see if there are any effects on age-related conditions,” Mannick says.

There is irony in an mTOR inhibitor’s seeming ability to boost immunity against the flu. In transplant recipients, the drugs do just the opposite — toning down immunity to help control immune rejection.

Kaeberlein says that the nature of drug exposure could have an effect. A “transient” exposure to mTOR inhibitors for several weeks that is then stopped — as in this study — might prime the immune system to react to the next challenge it faces, he says.

Meanwhile, dose might matter, too. He notes that the low dose used in this study is much less than transplant recipients would get. That’s a plus because high doses of mTOR inhibitors are linked to an increased risk of side effects including alterations in glucose metabolism and higher levels of lipids in the blood, he says.

The uncertainties surrounding mTOR, its role in the body and its inhibitor drugs have drawn plenty of attention. The National Institutes of Health lists nearly 1,700 clinical trials that include rapamycin or everolimus.