Quantum entanglement makes quantum communication even more secure

Quantum devices don’t have to be perfectly understood to be snoop-proof, three studies show

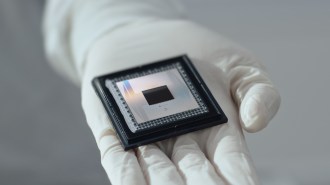

Quantum entanglement, a type of ethereal link between particles, improves the security of quantum communication, as demonstrated in three experiments (the one pictured, by researchers in France, Switzerland and England, used strontium ions in its test).

David Nadlinger/University of Oxford

Stealthy communication just got more secure, thanks to quantum entanglement.

Quantum physics provides a way to share secret information that’s mathematically proven to be safe from the prying eyes of spies. But until now, demonstrations of the technique, called quantum key distribution, rested on an assumption: The devices used to create and measure quantum particles have to be known to be flawless. Hidden defects could allow a stealthy snoop to penetrate the security unnoticed.

Now, three teams of researchers have demonstrated the ability to perform secure quantum communication without prior confirmation that the devices are foolproof. Called device-independent quantum key distribution, the method is based on quantum entanglement, a mysterious relationship between particles that links their properties even when separated over long distances.

In everyday communication, such as the transmission of credit card numbers over the internet, a secret code, or key, is used to garble the information, so that it can be read only by someone else with the key. But there’s a quandary: How can a distant sender and receiver share that key with one another while ensuring that no one else has intercepted it along the way?

Quantum physics provides a way to share keys by transmitting a series of quantum particles, such as particles of light called photons, and performing measurements on them. By comparing notes, the users can be sure that no one else has intercepted the key. Those secret keys, once established, can then be used to encrypt the sensitive intel (SN: 12/13/17). By comparison, standard internet security rests on a relatively shaky foundation of math problems that are difficult for today’s computers to solve, which could be vulnerable to new technology, namely quantum computers (SN: 6/29/17).

But quantum communication typically has a catch. “There cannot be any glitch that is unforeseen,” says quantum physicist Valerio Scarani of the National University of Singapore. For example, he says, imagine that your device is supposed to emit one photon but unknown to you, it emits two photons. Any such flaws would mean that the mathematical proof of security no longer holds up. A hacker could sniff out your secret key, even though the transmission seems secure.

Device-independent quantum key distribution can rule out such flaws. The method builds off of a quantum technique known as a Bell test, which involves measurements of entangled particles. Such tests can prove that quantum mechanics really does have “spooky” properties, namely nonlocality, the idea that measurements of one particle can be correlated with those of a distant particle. In 2015, researchers performed the first “loophole-free” Bell tests, which certified beyond a doubt that quantum physics’ counterintuitive nature is real (SN: 12/15/15).

“The Bell test basically acts as a guarantee,” says Jean-Daniel Bancal of CEA Saclay in France. A faulty device would fail the test, so “we can infer that the device is working properly.”

In their study, Bancal and colleagues used entangled, electrically charged strontium atoms separated by about two meters. Measurements of those ions certified that their devices were behaving properly, and the researchers generated a secret key, the team reports in the July 28 Nature.

Typically, quantum communication is meant for long-distance dispatches. (To share a secret with someone two meters away, it would be easier to simply walk across the room.) So Scarani and colleagues studied entangled rubidium atoms 400 meters apart. The setup had what it took to produce a secret key, the researchers report in the same issue of Nature. But the team didn’t follow the process all the way through: The extra distance meant that producing a key would have taken months.

In the third study, published in the July 29 Physical Review Letters, researchers wrangled entangled photons rather than atoms or ions. Physicist Wen-Zhao Liu of the University of Science and Technology of China in Hefei and colleagues also demonstrated the capability to generate keys, at distances up to 220 meters. This is particularly challenging to do with photons, Liu says, because photons are often lost in the process of transmission and detection.

Loophole-free Bell tests are already no easy feat, and these techniques are even more challenging, says physicist Krister Shalm of the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Boulder, Colo. “The requirements for this experiment are so absurdly high that it’s just an impressive achievement to be able to demonstrate some of these capabilities,” says Shalm, who wrote a perspective in the same issue of Nature.

That means that the technique won’t see practical use anytime soon, says physicist Nicolas Gisin of the University of Geneva, who was not involved with the research.

Still, device-independent quantum key distribution is “a totally fascinating idea,” Gisin says. Bell tests were designed to answer a philosophical question about the nature of reality — whether quantum physics really is as weird as it seems. “To see that this now becomes a tool that enables something else,” he says, “this is the beauty.”