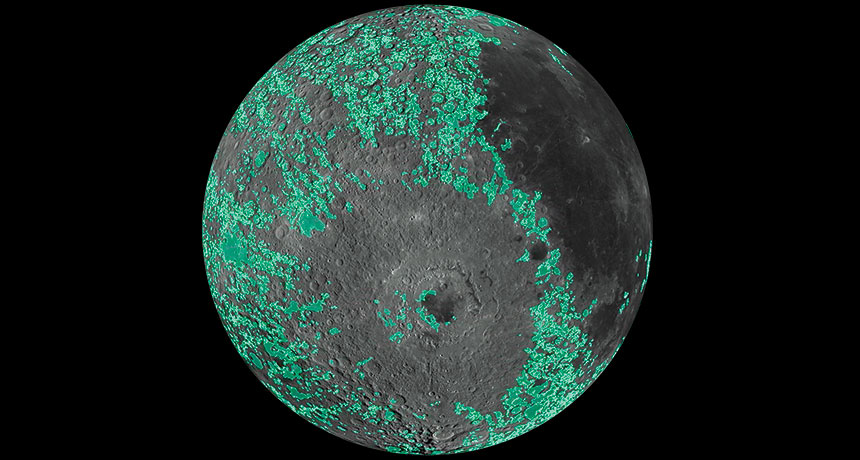

This spinning moon shows where debris from giant impacts fell

Most of the light-colored plains on the lunar surface point back to two huge impact basins

LUNAR LOOK A new moon map, compiled using data from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, is the most detailed global look yet at the moon’s light-colored plains (shaded green).

H. Meyer, L. Davis and N. Estes/LROC SOC-ASU