New fleets of private satellites are clogging the night sky

Global internet satellites are photobombing telescopes and messing with astronomers’ research

SpaceX is launching thousands of internet satellites (illustrated) into orbit. The night sky may never be the same.

Nicolle Rager Fuller

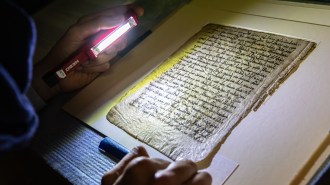

Astronomer Cliff Johnson was peering into deep space before dawn when something close to Earth interrupted his view.

He and colleagues were searching for dwarf galaxies snuggled up to the Milky Way using the Victor M. Blanco 4-m Telescope in Chile. The team was remotely operating the scope from a room at Fermilab in Batavia, Ill., about 8,200 kilometers away.

“We had a nice clear night,” says Johnson, of Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill. Through outdoor webcams at the observatory, the team could spy on the scene in the high Chilean desert. The sky was immaculate: inky black with dots of white starlight.

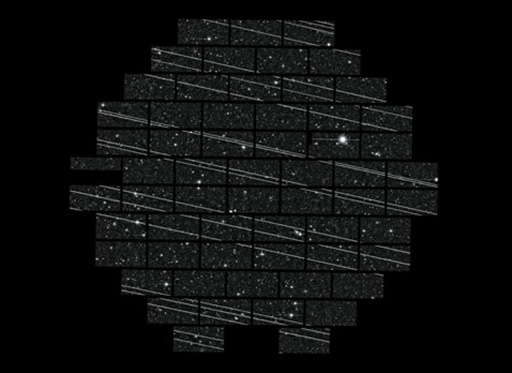

“All of a sudden, through this webcam, we started seeing these streaks popping through,” Johnson says. Dashes of white light shot across the view, like laser fire from a sci-fi battle cruiser. The intruders flew right across the telescope’s gaze: In a five-minute exposure with the scope’s camera, 19 white lines defaced the picture. It didn’t take long to realize the culprit.

A week earlier, on November 11, 2019, the aerospace company SpaceX had launched 60 Starlink satellites to join its growing fleet of satellites built for global broadband internet access. That flock of satellites in low Earth orbit had photobombed Johnson’s image.

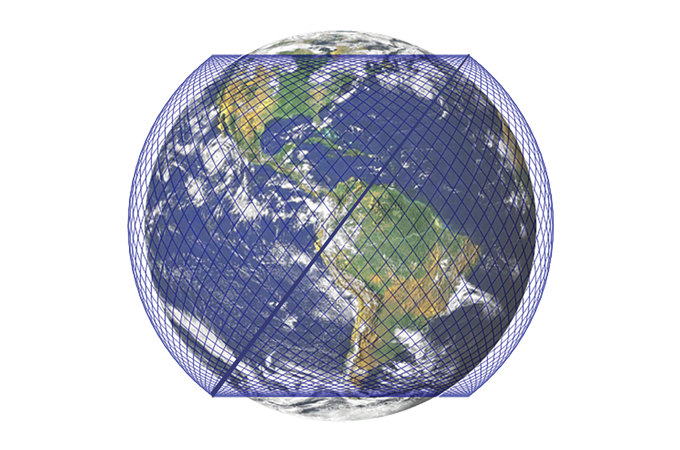

SpaceX plans to send up more than a thousand satellites in its first round of launches to provide near-continuous internet service to the United States and Canada by the end of 2020 and to all corners of the globe in 2021.

Through a webcam at Chile’s Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, Cliff Johnson, watching from Illinois on November 18, had a view of a clear night sky — until he didn’t (left). Newly launched Starlink satellites left 19 trails of light in one of his telescope images (right), obtained during a five-minute exposure on the Victor M. Blanco telescope.

These “mega-constellations” of satellites have triggered alarm bells: “Elon Musk’s satellites threaten to disrupt the night sky for all of us,” warned the Washington Post, calling out SpaceX’s celebrity CEO.

Researchers have begun to quantify the scale of the problem, and the news is mixed. Most of the new satellites will stay hidden to unaided eyes for much of the night, and small telescopes won’t often notice much difference. But large telescopes, especially those dedicated to sweeping the entire sky, may run into problems, reports a study posted on arXiv.org on March 4.

Astronomers discussed the issue on January 8 during panel sessions at an American Astronomical Society meeting in Honolulu. The group is concerned that hunting for asteroids that might impact Earth will be hampered, and flickering satellites could be mistaken for exploding stars.

“The issue of mega-constellations in astronomy is a serious issue,” said Patrick Seitzer, an astrophysicist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor who studies orbital debris. Tens of thousands of new internet satellites could blanket Earth in the coming years, many of them brighter than nearly every other artificial object circling the planet. Or as Seitzer put it: “Cheer up, the worst is yet to come.”

Shockingly bright

Artificial satellites have been getting in astronomers’ way since the launch of Sputnik 1 in 1957 (SN: 10/19/57, p. 245). Today, NASA estimates that roughly 20,000 known human-made objects larger than a softball — satellites, rocket bodies and other flotsam — are orbiting Earth. The number will keep growing, despite concerns about the risk of collisions that could put equipment and astronauts in danger. From observatories in Chile, Seitzer noted, there are about 600 to 700 overhead objects visible at any given time at night.

Sunlight reflected off metal surfaces and solar panels on those satellites can shine into a telescope and either mimic or hide things in deep space. Astronomers so far have been able to deal with that interference by taking multiple images and combining them for a cleaner composite picture. In some cases, image-processing algorithms can also recover data lost to intruding light. That’s getting harder, though, as more satellites are put into space. Plummeting launch costs, largely due to reusable rocket technology, have made low Earth orbit more accessible than ever.

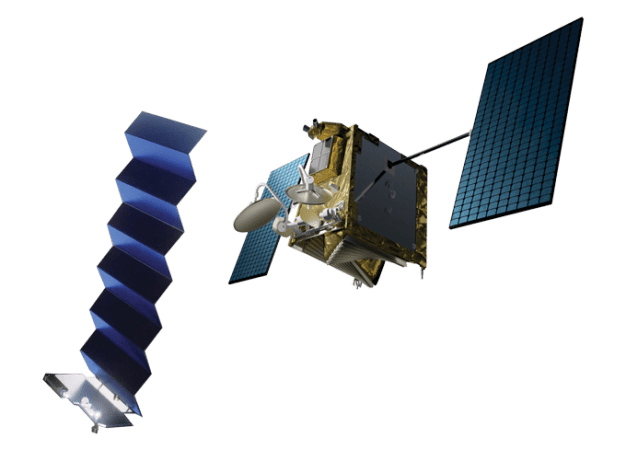

SpaceX, based in Hawthorne, Calif., launched its first 60 Starlink satellites in May 2019. A second batch went up in November and three more batches were sent aloft in the first two months of 2020. Eventually, the company says, it will have an initial fleet of 1,584 Starlinks in orbit, providing near-continuous internet service to most of the world’s populated areas.

“It’s estimated that 3.6 billion people don’t have access to the internet, and the U.N. considers broadband access as a key enabler to economic development,” Patricia Cooper, vice president of satellite government affairs at SpaceX in Washington, D.C., said at the January meeting. “We think space-based internet could be of real use to those goals.”

That internet service will be delivered via pizza box–sized ground devices that relay information back and forth to the satellites. To reduce delays in data transmission, the satellites will fly relatively close to Earth — several dozen times closer than typical communication satellites in geosynchronous orbit, an orbit in sync with Earth’s rotation. That connectivity comes with a cost, astronomers say — the clarity of our night skies.

“There is nothing bad about having internet delivered through these satellite mechanisms,” said Chris Impey, an astronomer at the University of Arizona in Tucson. “But of course, we’re worried about the side effects.”

Astronomers immediately noticed that the Starlink satellites launched in May were shockingly bright, much brighter than similarly sized objects already in orbit. Even SpaceX was surprised, Cooper said. The culprit seems to be surfaces that scatter light diffusely, but the company is still trying to figure out precisely what makes the satellites so dazzling against the sky.

When a batch is launched, the satellites appear to people on the ground as a “string of pearls” tracing the sky. But that effect is temporary. SpaceX launches its satellites into a relatively low orbit so that engineers can run diagnostics for a few weeks before moving the satellites to a higher operational orbit, where they spread out around the globe and appear fainter. Still, that distance may not be enough for the satellites to fully fade into the background.

Even when farther away, Starlink satellites “are brighter than 99 percent of all objects that are now in Earth orbit,” Seitzer said. He has been running computer simulations to quantify how much these satellites might affect astronomical observations. For SpaceX’s initial planned fleet of 1,584 Starlink satellites, Seitzer estimated that up to nine satellites would be visible to telescopes at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile for about an hour after twilight and an hour before dawn — and likely for longer during summer nights. In the middle of the night, the satellites vanish in Earth’s shadow.

“Astronomers could handle that” and work around the interference in their observations, Seitzer said — if only that was the total number of new satellites expected to launch. But 1,584 satellites is just the beginning for SpaceX, and other communication companies have their own internet satellites planned.

Uncertain future

SpaceX has permission from the U.S. Federal Communications Commission to launch and operate 12,000 Starlink satellites. And the company has filed with the International Telecommunication Union in Geneva for permission to broadcast to and from 30,000 more. Meanwhile, several other companies are keen to jump into the internet satellite market. Amazon, for example, has filed with the FCC for permission to operate 3,236 satellites. Communications company OneWeb has initial plans for 650 satellites, though CEO Adrián Steckel told Ars Technica in February that he has long-term hopes for as many as 5,260.

Internet satellite players

Several firms have sent up or announced plans to launch satellites into orbit to expand internet access worldwide. The satellite numbers below are estimates based on company data and news reports.

| Company | Estimated number of satellites |

|---|---|

| Space X | Up to 42,000 |

| OneWeb | 650–5,260 |

| Amazon | 3,236 |

| Lynk | Several thousand |

| Thousands | |

| Boeing | 1,396–2,956 |

| Telesat | 292–512 |

| Russia’s space agency, Roscosmos | 640 (internet and other satellites) |

| China’s Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation | 156 |

“This could easily grow to 50,000 or more,” Seitzer said. Instead of six to nine Starlink satellites in view at a time, astronomers might need to dodge a couple hundred bright satellites during twilight hours.

But Seitzer’s simulations assume that the satellites will be at SpaceX’s current operational altitude of 550 kilometers. London-based OneWeb, which launched 34 satellites in early February, adding to the six it launched in 2019, is putting its constellation in a 1,200-kilometer orbit, which SpaceX is also considering for later launches. At that height, the satellites might appear fainter from Earth. But that also means more of the orbit can be seen from the ground, leading to larger numbers of satellites visible and for longer into the night.

At the Cerro Tololo observatory, higher-orbit satellites would be visible all night long in the month of December, Seitzer said, when many would not disappear in Earth’s shadow. “I don’t like that equation,” he said. “I’d rather have the damage confined to a small time rather than have it go all night.”

The actual damage to any one scientist’s research depends on what’s being studied. For Cliff Johnson, the Starlinks in his November 18 image doubled the amount of unusable picture elements, or pixels, from about 10 to 20 percent.

“It’s annoying, but it’s not necessarily hurting the science all that much,” he says, referring to his work. Despite their name, the dwarf galaxies he’s searching for appear relatively large through a telescope and so a few satellite streaks won’t obliterate one image. And Johnson’s survey always takes multiple images of any one patch of sky, so there’s a chance to fill in lost pixels. “That’s not the case across the whole astronomical community,” Johnson says.

For astronomer Krzysztof Stanek of Ohio State University in Columbus, hordes of bright satellites in his telescope views could be a disaster. Stanek helps run the All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae, a network of 24 telescopes that scan the skies for exploding stars. On January 15, recently launched Starlink satellites flew in low orbit over one of the telescopes Stanek’s team was using, leaving streaks that remained in an image even after data processing that usually smooths over such blemishes.

“We have an image with about 10 trails comparable in brightness to what a distant supernova would be,” Stanek says. While that’s not yet typical, “I am extremely concerned that, once [SpaceX reaches] the projected size of the network, there will be multiple satellite trails crossing any given field of view at all times.”

Rubin’s dilemma

Already, scientists working on the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope — recently rechristened the Vera C. Rubin Observatory (SN Online: 1/10/20) — are anticipating trouble. Starting in 2022, the Rubin Observatory, also in Chile, will take images every three days of the entire sky for 10 years.

But reflected light from satellites could mess with twilight observations required for searching for Earth-threatening asteroids that might approach from the direction of the sun, says Tony Tyson, an astrophysicist at the University of California, Davis and chief scientist for the observatory. The arXiv.org study suggests that 30 to 50 percent of exposures taken around the beginning and end of the night will be “ruined.”

The new satellites also could jeopardize a study of how dark matter has evolved over cosmic history. That study depends on sensitive observations of faint galaxies that some satellite trails can mimic.

Recent experiments have shown that Starlinks are just too bright for Rubin’s detectors, Tyson says. Pixels are like little buckets of light that can overflow, leading to image streaks that completely mask light from the cosmos and to “ghost streaks” caused by electrical interference with neighboring pixels, all of which hinders data cleanup.

The observatory’s researchers are working on a three-pronged fix. They are developing new algorithms to recover some lost data in defaced images. The team is also looking into slowing the rate at which information is read from the image detectors, which can reduce electrical interference between pixels at the cost of slowing observations just a bit.

Finally, the group is testing whether it’s possible to sidestep the satellites altogether. The survey will use artificial intelligence to shift the telescope’s gaze from one patch of sky to another, while keeping bright objects like the moon and satellites away from the telescope’s view. However, a fully populated Starlink system could give the AI a headache.

“It works like a charm for maybe 1,000 [Starlink] satellites,” Tyson says. “Once you get above 10,000 satellites, it starts failing, and by the time you get to 50,000 satellites, it ends up in a wild goose chase.” The team is working with SpaceX to include Starlink orbit details within the AI itself, though it’s unclear how much that will improve things.

Cosmic Wild West

SpaceX has said it will fix the brightness problem, and some astronomers are cautiously optimistic about the company’s willingness to engage. One of the 60 satellites launched January 6 was coated with a substance to make the satellite darker than its siblings, and astronomers will be watching to see if that helps. But if the dark coating works and makes the satellite sufficiently faint to optical astronomers, scientists who use infrared telescopes might not be thrilled — a dark satellite absorbs more heat, making it brighter to those telescopes.

Researchers who are less impressed by SpaceX’s response wonder why the company darkened only one satellite in its fleet. “If they were serious about it, they would have stopped launching more satellites,” at least temporarily, Stanek says. “They would conduct a good scientific study of their impact, and then maybe they would start launching again.”

Cooper, the SpaceX representative, confirmed at the January Honolulu meeting that the company will continue launching unmodified satellites — a fourth batch went up January 29 followed by a fifth on February 17. The next launch, from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center at Cape Canaveral, Fla., is scheduled for March 14.

As recently as March 9, SpaceX CEO Elon Musk declared that Starlink will have no impact on astronomical observations. “Zero. That’s my prediction,” he said at the 2020 Satellite Conference in Washington, D.C. “We’ll take corrective action if it’s above zero.” OneWeb did not respond to requests for comment, while an Amazon representative said the company is not granting interviews at this time.

Private companies face little international oversight on their activity in space, so there is no guarantee that SpaceX will continue to work on the problem or that other companies will collaborate with researchers on ways to minimize the potential damage.

And that’s the rub: When it comes to rules on private companies, space is the Wild West. Negotiations to establish regulations would require cooperation among many countries, possibly mediated by the United Nations, and that could take many years to work out. The International Astronomical Union said in a Feb. 12 statement that it will regularly brief meetings of the U.N. Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space to bring “the attention of the world government representatives to the threats posed by any new space initiative on astronomy and science in general.” But the satellite launches are happening now, so astronomers can only hope that private companies are receptive to their concerns.

Scientists also realize they have to balance their desire for clear skies with the potential benefits of expanded internet for those without access. At the January meeting, Pamela Gay, an astronomer with the Planetary Science Institute who is based in Edwardsville, Ill., asked speakers at one of the conference panels: “How do we argue to save the skies but not allow low-cost internet to be an option to remote places?”

Panel members agreed that a swarm of low-orbit satellites is the most cost-effective way to establish fast, reliable internet across the globe. But the astronomers also hope companies will think of the night sky as a natural resource to be protected, like a national park, and minimize the disturbance from internet satellites.

“We can have these two things together,” said Ruskin Hartley, executive director of the International Dark-Sky Association in Tucson. “We need to come up with a way that we can help bring the social groups of the world to technology and innovation that protects the heritage of dark skies around the world.”