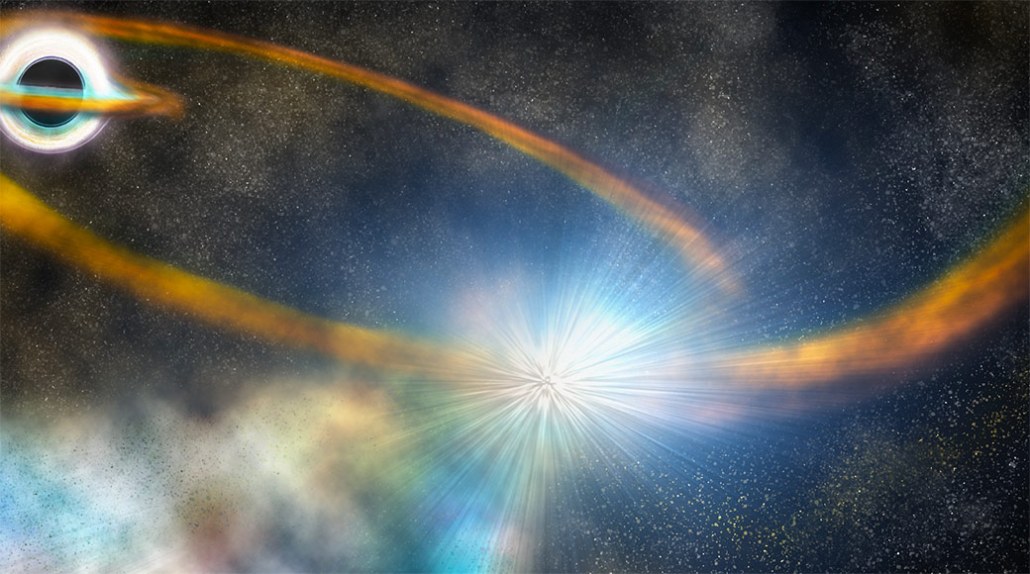

In this illustration, a star that wanders too close to a black hole (top left) is stretched into a spaghetti-like strand with part of the stellar remains flung into space.

Robin Dienel/Carnegie Institution for Science

Every so often, a celestial slasher film plays out in the heavens, as a supermassive black hole shreds a star and swallows part of it. Now scientists have gotten a rare, early glimpse of the show.

The episode, described September 26 in the Astrophysical Journal, was first detected by telescopes in January and named ASASSN-19bt. It’s one of only dozens of these phenomena called tidal disruption events that astronomers have observed.

Such an event, when a star passes close enough to a black hole to get sucked in and torn apart, occurs only about once every 100,000 years in any given galaxy, says Suvi Gezari, an astronomer at the University of Maryland in College Park, who was not involved with the work. “This is really exciting,” she says.

The first clues that scientists saw from ASASSN-19bt came from robotic telescopes that had been searching the sky for supernovas, or violent explosions that mark the death of massive stars (SN: 2/18/17). When the telescopes instead caught a bright flare from the event, researchers turned to other instruments to get a better look.

As it happened, that patch of sky was also being watched by NASA’s TESS satellite, which searches the sky for exoplanets (SN: 4/12/18), planets that orbit stars outside of Earth’s solar system. The TESS data, captured every 30 minutes, revealed the stellar material brightening as it began circling the black hole.

“We were able to see exactly when it started to get brighter,” says Thomas Holoien, an astronomer at the Carnegie Observatories in Pasadena, Calif. That’s the earliest observation of a tidal disruption event yet.

The energy emitted by ASASSN-19bt, in a galaxy around 375 million light-years away from Earth, was about 30 billion times the energy of our sun. A typical galaxy contains around a billion or 10 billion stars, “so this was outshining every other star in its galaxy,” Holoien says. If such an event happened in the Milky Way, it would be so bright that it could probably be seen during the day.

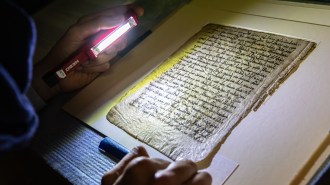

As the star was drawn in by the black hole, it was pulled apart by the intense gravity of the black hole until eventually the star was stretched into a long strand of gas. Some of the shredded stellar guts were spit back into space. The rest looped around the black hole, crashing into itself and forming a spiraling ring of glowing, hot gas called an accretion disk.

A star is torn

This video shows what happens when a star strays near a black hole and is shredded into a thin strand of gas, a process known as a tidal disruption event. Included in the video are images of an event named ASASSN-19bt and an animation of this process.

The accretion disk is like “water circling the drain of a bathtub,” says theoretical astrophysicist Nicholas Stone of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Stone was not involved with the work, but collaborates with one of the paper’s authors. “It’s superheated, interstellar gas, but it still behaves like a fluid.”

More early observations of tidal disruption events could help physicists improve estimates of the masses of black holes and how quickly they spin, Stone says.

Such data also could help answer how black holes form, and whether this type of star-shredding activity plays into galaxy evolution, Holoien says. “This star died, but we’re able to use its death to learn about the universe.”