This Stone Age wall may have led Eurasian reindeer to their doom

The underwater structure functions similarly to ancient traps in North America and the Middle East

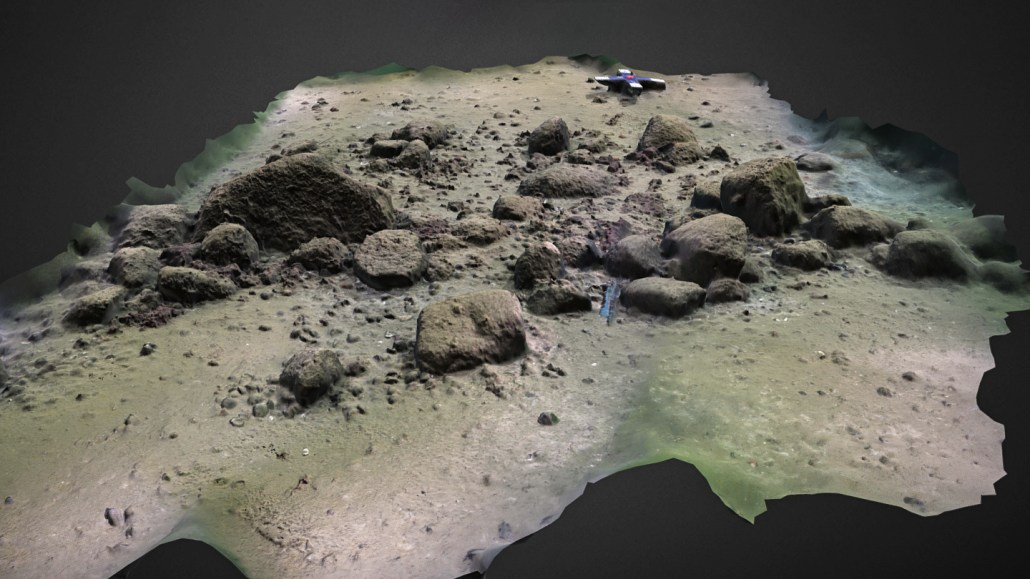

These stones at the bottom of the Baltic Sea off the coast of Germany were part of a wall that Stone Age hunter-gatherers may have used to hunt reindeer, scientists say.

Philipp Hoy

If this underwater wall could talk, it might reveal that it once helped Stone Age Europeans hunt reindeer.

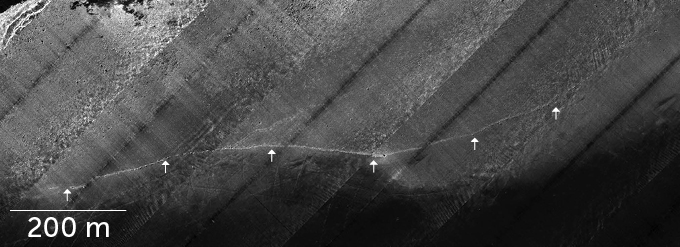

Submerged about 20 meters below the surface of the Baltic Sea off the coast of Germany, the wall stretches for almost a kilometer and contains nearly 1,700 stones, making it among the largest human-made megastructures in Northern Europe, scientists report February 12 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

The team suspects it was used for hunting large prey, similar to ancient hunting traps in the Middle East and North America (SN: 5/17/23). If so, it would be the first known trap of its kind in the southern Baltic region.

Researchers discovered the structure, dubbed the Blinkerwall, while mapping seafloor depths with sonar in 2021. The data revealed odd protrusions down below, so the team returned with underwater cameras to get a better look.

“When we found the rocks, I realized it’s possibly not a natural process that put these rocks together,” says Jacob Geersen, a marine geologist at the Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research Warnemünde in Rostock, Germany.

It’s unlikely that tsunamis, glaciers, ice floes or construction of nearby underwater infrastructure could have positioned the rocks into their flattened S-like shape, Geersen and colleagues say. The rocks seem to be intentionally placed, with the largest boulder (calculated to weigh over 11,000 kg, or the weight of seven mid-size cars) sitting in the middle. Most of the other rocks weigh less than 100 kg — light enough to have been moved by people to connect the larger rocks scattered along the wall’s length.

Radiocarbon dating of sediment cores taken from near the Blinkerwall suggest that a lake bordered the structure around 10,000 years ago, before the Baltic Sea rose 8,500 years ago and submerged the area. The wall probably funneled Eurasian reindeer — which last occupied the area around the time the wall was built — towards the nearby lake, where the trapped prey could have been easily killed. At that time, the only people in the region who could have constructed such a large wall were nomadic hunter-gatherers, says study coauthor Marcel Bradtmöller, a Stone Age archaeologist at Rostock University.

The wall provides insights into how people at that time worked with the land and each other. It likely required a group of at least 10 people to use the structure to hunt, says Bradtmöller.

Humankind has a long history of enhancing natural topography to obtain resources, says archaeologist Geoff Bailey of University of York in England. The team’s interpretation of the findings “sounds, to me, to be very plausible,” he says.

Now there’s more work to do, Geersen says. He and colleagues plan to take more sediment samples from under the rocks and search for artifacts near the wall, which could reveal clues about the people who lived there.