It’s the deep-sea version of “men are from Mars, women are from Venus.” With “kids are from Neptune” thrown in.

Scientists have just realized that all of the supposed species classified in the bignose fish family are actually males of fish in another family, the whalefish.

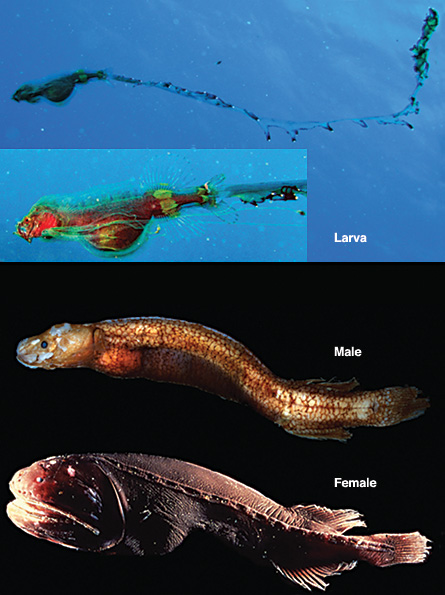

And species of a third supposed family, the tapetails and hairyfish, are in fact the larvae of these whalefish.

The three groups look quite different from each other, especially around the head. Yet DNA and a mix of new and reinterpreted specimens reveal that these three families are one, says Dave Johnson of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

The work places into one family species once considered to be from three different families. From now on, Johnson and his colleagues say in an upcoming Biology Letters, fish from any of the groups should be classified in the Cetomimidae, or whalefish.

In more than four decades of describing fish species, coauthor John Paxton of the Australian Museum in Sydney says he’s never done such a drastic reclassification. “These were families — it’s a big deal,” he says.

Such an upheaval doesn’t shock fish biologist Matthias Schneider of the Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum in Frankfurt, Germany, though. “The knowledge of deep-sea fish in general is quite scarce compared to fish from more accessible parts of the ocean,” he says.

Whalefish frequent depths below 1,000 meters. Their name comes not from their size but from their big heads. Of the 600 some whalefish specimens in the world’s museums, most are clearly female, Paxton says. Yet, he adds, reproductive biology specialists had told him, wrongly it turns out, that the few ambiguous specimens looked rather male.

In a 2005 book, Paxton and Johnson acknowledged that the specimens of the old tapetail and hairyfish family were larvae of some unknown adult form. But the youngsters didn’t look at all like whalefish, the researchers wrote then.

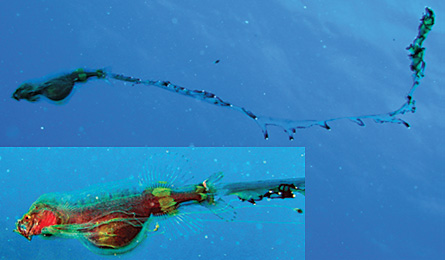

Tapetails take their name from their thin streamer tail, sometimes nine times the body length of the larvae. Adult forms of the fish don’t have the long tail. But more surprising, say Johnson and Paxton, would be the transformation of the head. Larvae have modest, upslanting mouths, for example, very different from adult female whalefishes’ huge, low-slung gapes.

Thus Paxton was skeptical when, in 2002, geneticist Masaki Miya of the Natural History Museum and Institute in Chiba, Japan, emailed about DNA from a new-found tapetail larva. Genetically it was a whalefish, Miya said.

Analyzing the DNA had consumed the entire specimen, though, so Miya wasn’t able to show his tapetail around for discussions of larval transformation. And he couldn’t just pull another tapetail out of a collection to test because the world’s hundred-plus specimens at the time had been preserved in Formalin, which sabotages attempts to recover DNA.

Yet studying the morphology of specimens eventually changed Johnson and Paxton’s minds. For example, when going back to old larval “tapefish” collections, Johnson saw the beginnings of what could be the outsized nasal organ of the male adult “bignose.”

Collecting deep-sea specimens is difficult and expensive, but several recent exploration voyages found males that let Johnson figure out their lifestyle. That lifestyle, it turns out, fits with what was known about larval feeding on copepods. While examining internal organs, Johnson discovered that adult males don’t eat, but instead apparently live off energy stored in their liver after youthful gorging on copepods. The specimens showed no esophagus or stomach but remnants of a massive copepod feast.

A bignose “is just giant testes with a giant nose, trying to get to a female before its liver runs out,” Johnson says.

At a critical moment in the study, coauthor Tracey Sutton of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science in Gloucester Point found a missing link: the only specimen known so far of a larva changing into the adult female whalefish. At last, Johnson and Paxton could see how the transformation happens. Whalefish are unique among vertebrates, they say, for combining such extreme transformations and such extreme differences between the sexes.

All the new collecting offered tissue that Miya’s team could use to sequence the mitochondrial DNA from all three of the former “families.” Miya, now a coauthor on the new paper, has confirmed that male and larval whalefish have at last been found.