Tiny human intestine grown inside mouse

Gut tissue in rodents could test patient-specific disease treatments

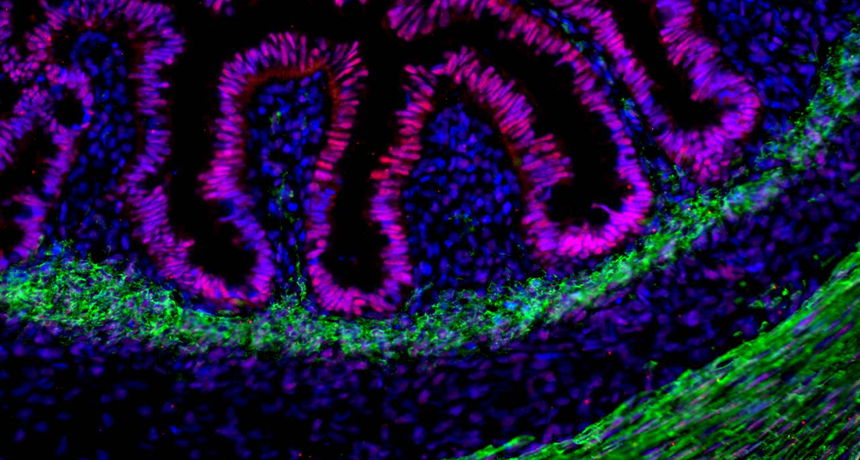

LOOKS LIKE A GUT Transplanted into mice, tiny specks of human intestinal tissue (stained pink) develop into working organs surrounded by a muscular sheath (stained green), just like real intestines.

Helmrath lab

Slimy chunks of human gut can now grow up and get to work inside of mice.

Transplanted into rodents, tiny balls of tissue balloon into thumb-sized nuggets that look and act like real human intestines, researchers report October 19 in Nature Medicine.

The work is the first time scientists have been able to transform adult cells into working bits of intestines in living animals. These bits could help scientists tailor treatments for patients with bowel diseases, such as Crohn’s disease or cancer, says study coauthor Michael Helmrath, a pediatric surgeon at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. Doctors could test drugs on the gut nuggets and see how a patient’s tissues respond without having to subject the person to a slew of different treatments.

“If you give me a patient, I can grow their intestines,” Helmrath says.

For decades, researchers have tried and failed to cultivate human guts in the lab, says stem cell biologist Eduard Batlle of the Institute for Research in Biomedicine in Barcelona.

Transplanted fetal tissue can turn into something like intestines, but it’s ethically sticky and the tissue wouldn’t match up with a patient’s own. In recent years, scientists have started to see glimmers of success in turning mature cells into organs. Using adult cells reprogrammed into an embryonic-like state, researchers have grown a variety of tissues, including heart, liver and brain (SN: 12/28/13, p. 20).

Still, converting clumps of tissue into three-dimensional organs remains a challenge — especially for organs with lots of different cell types. The intestine is a complicated structure, says UCLA stem cell biologist James Dunn. The muscular tube wriggles and writhes as food snakes through and houses cells that ooze mucus, absorb nutrients and break down sugars.

In 2011, Helmrath’s colleagues successfully created specks of human intestinal tissue from reprogrammed cells. The specks were like intestinal newborns: They didn’t behave quite like adults. Helmrath and colleagues thought transplanting the specks into a blood vessel–rich nook in mice might help the tissue mature.

The team created intestinal tissue specks from adult blood cells and then embedded them into gluey lumps of gel. Next, they placed them inside mouse abdomens and held the lumps in place underneath a filmy membrane that clings to the kidneys like hot dog skin. When researchers peeked inside the mice six weeks later, they discovered plump pink organs.

“We were like, ‘Whoa, this is an intestine,’” Helmrath says. “We didn’t have any idea that it was going to grow and develop so beautifully.”

Inside mice, the little specks of tissue had bloomed into organs 50 to 100 times their original size. The squishy tubes could absorb and digest food. They even responded to major surgery as real intestines do: When researchers cut out half of a mouse’s own bowels, the new organ grew to compensate for the loss.

“This is exciting work that’s going to move the whole field forward,” Dunn says. “But we’re still missing some elements.”

For one, the intestinal hunks live in an odd home, on the kidney. And they lack nerve cells, which typically prompt guts to clench and move. Helmrath says his team is working on the nerve-cell problem. “We’ve actually already figured it out,” he says. “But that’s not for this paper.”