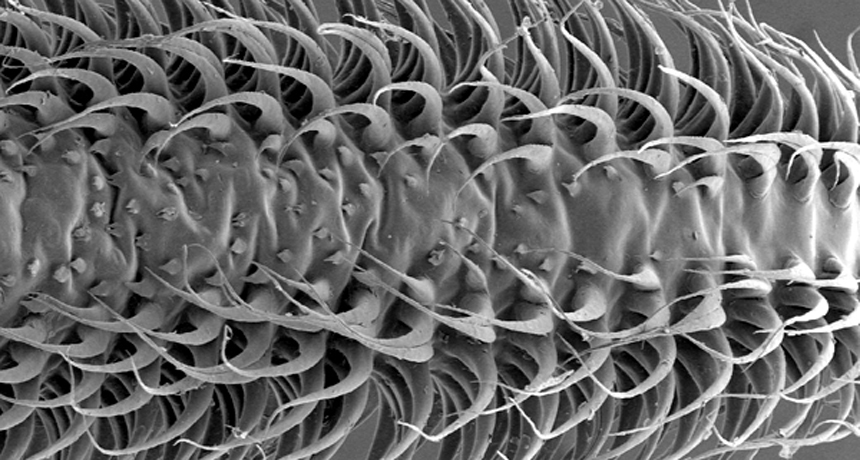

BRILLO TONGUE Rows of bristles line the tip of some nectar-feeding bats’ tongues and spring out to gather nectar when blood fills them during feeding, or when artificially pumped full of liquid, like the tongue tip shown in this scanning electron micrograph.

Courtesy of Cally Harper