TWICE AS NICE Mei Lun and Mei Huan (shown here at about two months old) are the only surviving panda twins born in the United States. These twins, born at Zoo Atlanta, recently celebrated their 2nd birthday.

Courtesy of Zoo Atlanta

Update: On August 26, the National Zoo reported that the smaller of the twin panda cubs born to Mei Xiang had died. Zookeepers, who had been caring for the giant panda cub by hand for two days, had been concerned about its fluctuating weight and noted that the days just after birth are a high-risk period.

Update, August 28: The National Zoo reports that both the surviving cub and the cub that died are males fathered by Tian Tian, a male panda at the National Zoo.

It was Saturday morning, August 22, and Mei Xiang was restless. The giant panda roamed outside her den at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo — but when she took a moment to stay still, keepers saw what they’d anticipated.

Contractions rippled across the pregnant panda’s belly. Mei Xiang was about to have her baby.

Panda pregnancies always make big news in mainstream and social media, but they elicit substantial scientific interest, too. Scientists in China, for instance, have recently mapped out how baby pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) develop. And a different team has discovered that giant panda sperm may be pretty hardy.

That could be good news for Mei Xiang, who was artificially inseminated in April. Until a few days ago, the panda’s keepers hadn’t known for certain she was pregnant. Giant pandas don’t grow giant bellies.

FIRST BORN The first of twin panda cubs born Saturday gets an exam at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo. At just 86 grams, the cub was much smaller than its 138-gram younger sibling, who was born about five hours later. Smithsonian National Zoo/YouTube |

Panda fetuses are often difficult to spot “because the female is extremely large, and the baby is really, really tiny,” says reproductive physiologist Pierre Comizzoli of the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute. But on August 19, the panda team got a clear ultrasound image: a light gray blip in a fuzzy image full of static. It was enough to tell the scientists, “Oh yeah, there is definitely a pregnancy,” Comizzoli says.

Late Saturday morning, the laboring panda returned to her den and lay still. Her water broke that afternoon, and just over an hour later, she gave birth to a tiny squalling cub. The wriggling pink bundle weighed 86 grams, about the weight of a newborn kitten. Less than five hours later, Mei Xiang delivered a second cub, about 1½ times the size of its twin.

So far, both cubs are “really active and energized, and in good health,” Comizzoli says. He sketched out a rough timeline of their expected growth.

The cubs look mostly naked now, and their eyes and ears are closed. But in eight to 10 days, tiny hairs will sprout from the skin in a black-and-white pattern. By day 21, the cubs’ fur will fill in, and by day 50, their eyes will begin to open. Around day 75, their eyes will open fully.

Just three months after birth, a typical panda cub could weigh more than 5 kilograms — roughly 36 times as much as their birth weight, Chinese researchers reported in March in Genetics and Molecular Research. In an analysis of size and weight of 83 giant panda cubs, the team discovered that cubs grow fastest when they reach about 75 days after birth, gaining on average 74 grams (about the weight of about two hamsters) per day. The findings could offer panda breeders benchmarks for growth, the authors suggest. So if cubs aren’t gaining enough weight, caretakers could adjust the pandas’ diets.

To help Mei Xiang’s cubs grow, the National Zoo’s panda team is working around the clock. For giant pandas, having twins isn’t that surprising — it happens in about half of pregnancies — but caring for two cubs can be challenging, Comizzoli says. “If one cub is a little bit weaker than the other one, it might not receive all the attention or milk that it requires,” he says. To boost the cubs’ odds, keepers are trying to periodically swap out babies. Every three hours or four hours, zoo staff hopes to place one cub in a warm incubator, giving the other cub time to nurse with Mei Xiang.

“I think it’s a great idea,” says Stephanie Braccini, the curator of mammals at Zoo Atlanta in Georgia. In 2013, the first surviving panda twins born in the United States were born at Zoo Atlanta. To take care of the cubs, the zoo followed a cub swapping technique first developed by colleagues in China. The National Zoo is now attempting to follow a similar plan.

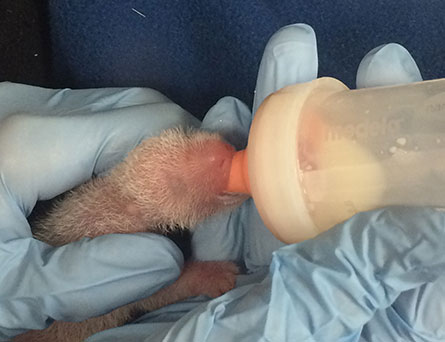

Switching cubs isn’t easy: Caretakers have to sidle up to the panda, and gently replace one cub with the other without bothering mom. And sometimes, Mei Xiang doesn’t cooperate. Since Monday afternoon, she’s been hanging onto her bigger cub, so the team has been manually feeding the smaller twin with formula.

Soon, the panda team will perform a DNA test to determine the cubs’ father. It could be Tian Tian, of the National Zoo, or Hui Hui, who lives in China. No one knows yet if the cubs are identical twins, or whether they even have the same father, Comizzoli says.

He and his team used frozen sperm from Hui Hui and fresh sperm from Tian Tian for Mei Xiang’s insemination. A cub fathered by Hui Hui would be especially exciting because it would get a diverse mix of genes from its parents — and that’s important for avoiding inbreeding within captive populations, Comizzoli says.

The team used Tian Tian’s sperm as a backup, in case Hui Hui’s sperm wasn’t lively enough. But there’s new evidence that giant panda sperm can survive repeated bouts of freezing and thawing, researchers reported online in August in Andrologia. Even after two freeze/thaw cycles, more than 50 percent of the panda sperm tested were still motile, the research team found.

Editor’s note: This post was updated on August 28, 2015, to correct the possible paternity of the panda cubs. Mei Xiang was also inseminated with sperm from Hui Hui, a panda in China, not Gao Gao of the San Diego Zoo, as previously reported.